SPIRIT MOUND

Begin with the naming of things.

“Prairie,” from French via the Vulgar Latin

prataria and further back to the Latin pratum,

meaning “meadow.” And the mound itself,

called by geologists a roche mountonếe—

a bedrock knob shaped but not leveled

by the last Pleistocene glacier.

But long before these names, known to the Omaha,

Oto and Yankton Lakota as Paha Wakan,

an evil place inhabited by humans

eighteen inches high.

Who, according to legend,

killed anyone in range

with tiny arrows.

Then profile the prairie itself: tall

rather than short-grass, and a century

after pioneers ground it under for corn

whisper a word gashed by their plow:

“ecosystem,” from the Greek oikos: house.

This then is the house I wander,

this small island with roots up to nine

feet down surrounded by a cultivated sea,

each plant a separate room

in which the naming practice blossoms.

Here are bluestem and sideoats grama.

Wild bergamot.

Ox-eye and milk-vetch.

The gray-headed coneflower.

Cordgrass. Indian grass.

Goldenrod and panicum virgatum.

When I reach the top I bite

into my apple and face west.

Isn’t that what Lewis and Clark did

when they climbed this hill of Niobrara chalk?

West. Where the sun kindles rebirth.

Like this site seeded, then restored

to what the explorers saw

on their walk through Dakota country.

Except for the wound that won’t close.

From the mound they counted

more than 800 buffalo and elk.

This morning bison bison is missing.

Vanished from the oikos.

The house whose door,

dangling from one remaining hinge,

clatters against its windblown frame.

As happens often with my poems, this one began with a first line that grabbed me and wouldn’t let go. I was at the University of South Dakota in the fall of 2009 as a reader at the John Milton Conference, and when it was over I drove a few miles out of town to a preserve of tall grass prairie that a friend had recommended to me. For most of my life I’ve had a deep and abiding love affair with the landscapes and history of the American West, particularly with respect to the flora and fauna that thrived there before Anglo-European civilization overwhelmed and utterly transformed it. And there’s something emotively powerful about intact prairie grasses that no amount of corn rows can match.

At Spirit Mound, interpretive signs identified the different varieties of grasses all along the path that wound through the preserve. The longer I was there, the more that identification impinged upon me. Thus the opening line: “Begin with the naming of things.” Not only did it feel like a strong, direct declaration, but it also afforded ample room for developing the poem. The naming process, with its window into derivations going back to earlier layers of culture and time, gave the poem scope and reverberating layers. The fact that Lewis and Clark had come through this exact spot gave the possibilities for the poem added resonance. For me, the most memorable statements by the two explorers about their journey have always been their amazed descriptions of the animals they encountered on the Great Plains, descriptions made all the more poignant because of what happened to them as Americans moved west. It was impossible to experience these isolated remnants of true prairie and not feel a sweep of history and loss as stinging as a blue norther.

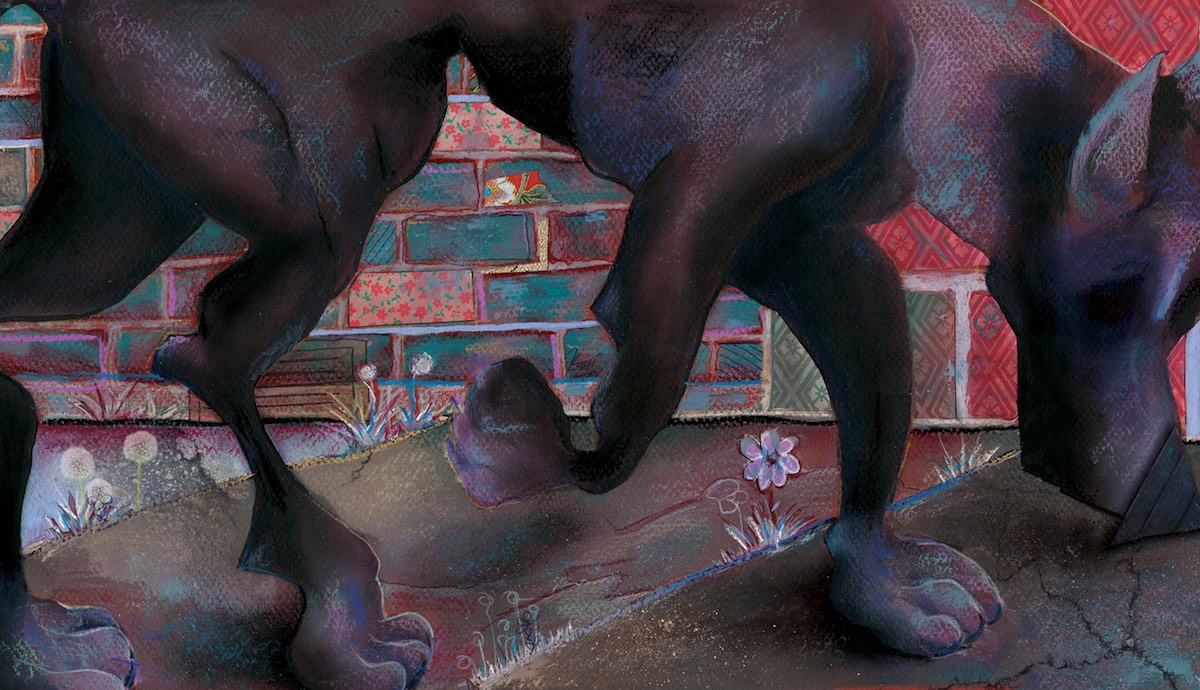

Illustration by Kali Gregan. Kali Gregan is an illustrator based in Richmond, Virginia who finds inspiration in Cubism and collage.