Line

There are rungs across the plains. If you’re ok with not looking too close, they become the kind of ruled mirage you find on cereal box stickers where holographic animals twitch and transform by tilting the angle of the card. If you don’t mind squinting, tree stands turn to their fields and caress the pastured cheeks. Take a step back and silos lean to hold one another’s hips. There is living in nondescript places, trust me. The Midwest, the driftless area, the relief map I’ve bent myself over, all the cold, brave province. Listen and it will ask if you are available enough to be cared for. The floodplain, too: collect every flatness in the pocket of your jaw. Let them still. Cross your eyes and they’ll be what you actually came here for. They’ll sing, these bright latitudes. They’ll belt, these dump truck hearts.

from NAR 302.2

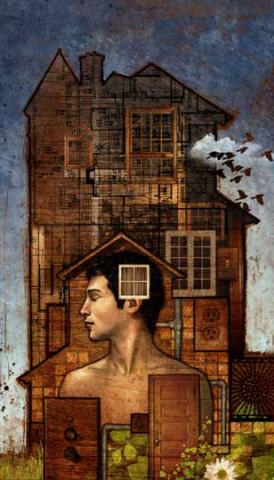

The house is a converted barn on the highest point in Burr Oak, a collection of trailers and farmhouses just north of the crescent beltline that cups Madison, Wisconsin. Passing cars broadcast an airy thrum punctuated by gutteral truck blasts. Freight cars tear across a cobbled train bridge, sweeping stands of sugar maple into shudders. The air there churns. Growing up there gave me the sense that everything outside of the house was constantly moving. On the refrigerator door hangs a laminated page, the final quote of Luc Sante’s My Lost City: “Whatever happens, whether I like it or not, New York City is fated always to remain my home.” It’s been there as long as I’ve been able to read. My parents moved to Madison from Brooklyn, New York, in 1991, two months after I was born. I’m not sure if displacement can be engendered, but the way that my parents regarded the move instilled the sense that I’d lost a home I’d never known.

My relationships with Wisconsin and New York City are at once affectionate and disdainful, and only comprehensible (and even then, barely) when I am apart from these places. However, I think a more important understanding of place marks my cognizance. This is place as imagined/felt/created space, and, in (what I see) as a necessary extension, spiritual space. And in this domain, as described by Larry Levis, separation is also a major force: place, he asserts, “is often spiritual, and yet it is important to note that this spiritual location clarifies itself and becomes valuable only through one’s absence from it.” By chasing the ghosts of spaces I must recreate them, each iteration a wholly independent fiction, yet wholly necessary, and perhaps the impetus for writing at all. It’s landscapes of all kinds, literal and figurative, and the intrinsic nonexistence of them beyond the self that lend themselves as subjects. James Galvin advises to “write about what you don’t know about what you know.” There’s so much I want to discover about the places I know intimately, and it’s the impossible pursuit of those places that allows me to know anything, really, about myself or the world outside of the way I believe I’ve experienced it.