The Polish government designated it the Year of Zbigniew Herbert and organized a celebratory reading at the Polish Embassy in DC, where a handful of Polish American poets read and discussed his singular influence. I read a Herbert-influenced poem along with an excerpt from my translation of Pan Tadeusz, the great nineteenth century Polish Romantic epic—the scene where all nature and all the inhabitants of Lithuanian Poland react to the advancing Napoleonic forces with an eerie mix of horror and exultation.

War! War! In Lithuania there is no

place so remote, no province so far

away that sounds of war could not be heard . . . .

Men who had known no other guests than beasts

that shared the woods, heard sounds they couldn’t recognize:

the sky strangely aglow, something released,

which seemed to stray from the field of battle,

seeking the forest where it tore up stumps,

shredded branches, uprooted the nettle.

The bison in the moss raised up their rumps

and shuddered, the long gray hair of their manes

bristled as they propped themselves on front legs

and gazed at the wondrous sparks in the heavens—

when all of a sudden, amid some twigs,

a smoldering shell whirled and hissed,

and split apart a trunk like a lightning bolt.

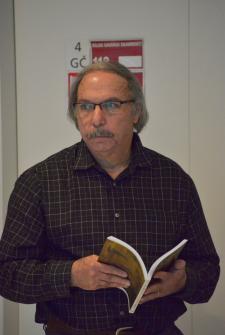

The evening was titled Barbarian in the Garden, after Herbert’s book of essays. A highlight of the evening was the introduction and discussion led by the book’s translator, Jaroslaw Anders. I tried to make the point that the “garden” was the Polish/Lithuanian countryside, the fields and vast forest . . . and that the “barbarian” was not only the invading French and Russian forces but also the crazed, pitched fervor for war infecting Poles too—bloodlust for salvation. I also wanted to make the point (to the audience of Polish American historians and Poles) that we should recognize what they were feeling at the time, since that same insanity has existed since 9/11. I’m not sure the audience got my point; I don’t think I articulated it clearly enough. I was especially nervous because the guest of honor was General Edward Rowny, former ambassador to Poland and Reagan’s chief arms negotiator with the Soviets, and I could imagine his position. He was invited because his book, It Takes One to Tango, had just been translated into Polish, but to me he was the American general who single-handedly introduced the helicopter into the Vietnam War and all I could think of was Apocalypse Now and M*A*S*H.

At the same time, my own little drama was playing out. I had spent the day on the D.C. Mall—the Hirschhorn with chambers packed with Morris Louis’ vaporous large-scale color fields. Followed by the National Gallery, where I feasted upon seventeenth century Flemish edible still-lives. I was visibly sated and overwhelmed as I alternately jogged and stumbled back to my hotel to rest before the Herbert event.

When it was time to go, still in walking mode, I gave myself a half hour to venture further up 16th Street to the Embassy, which according to Google Maps, was a mile away. It turned out to be more like two and pretty much uphill. I was growing increasingly nervous that I wouldn’t make it on time. I did manage to arrive a few minutes early and after my backpack was searched by an apologetic Polish soldier, went upstairs where I encountered a table teeming with cut-glass stemware. Thirsty from the walk, my throat too dry to give any sort of poetry reading, I grabbed a glass of what looked like punch. I gulped it down before realizing it was grapefruit juice, which would be a good thing, unless like me, you take medication for high blood pressure which interacts dangerously with some citrus. So the whole time I anxiously expected to keel over or go into convulsions. To make things worse, the room was packed and the podium was pushed back—right up against a decorated Christmas tree. The reader before me had brushed against it and one of the glass ornaments had crashed down and shattered, though I seemed to be the only one who noticed. I was sure that when it came my turn to read, my clogs would crunch over the glass shards and everyone would be thinking I was the ornament shatterer—the barbarian in the room. I was certain the grapefruit juice would react with my medication causing some sort of seizure, just like Dostoevsky’s idiot, Prince Myshkin, and I would be writhing on the floor—to the audience’s bilingual tsk-tsk-ing.