I have two best friends, and they are biological sisters. When one sister’s husband became very ill, some old high school buddy randomly texted, asking me about the husband’s health. When I asked the other sister what was going on, she said (with kindness), “It’s not my story to tell.” The saying has become a catchphrase. It’s a way of saying that we respect each other’s privacy. It’s a way of protecting what’s precious.

So, while I, at a party, with brand new friends, responded to Jean Cocteau’s famous answer to the question of what he would save if his house ignited (the famous answer is: I would save the fire), it’s true that I spoke of how my Baltimore rowhome once burned down. But I was speaking as you speak at parties, superficially and in a manner where complexity becomes contracted. The way you speak when you believe you are among friends.

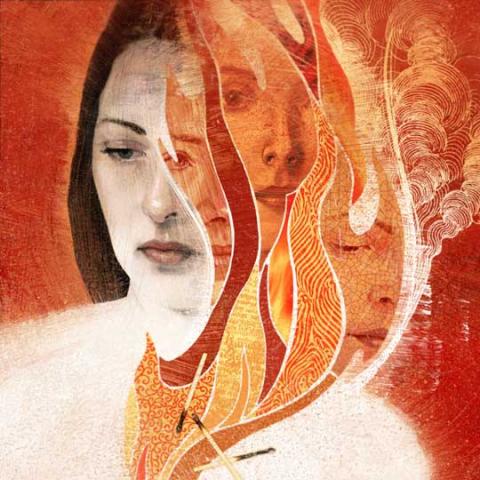

In that fire, I lost many material things. I lost privacy and pride. There’s a great deal of humiliation that comes with being the victim of a housefire, especially when it happens on a crowded city street, where you’re separated from your neighbors by only a wall and the totality of your belongings are thrown onto the front yard for you tread through, an embarrassing bazaar of all your essentials still steaming and smoking. Neighbors on the sidewalk.

Take into consideration that you cannot save the fire without saving its destructive qualities.

True, we’d moved two weeks before and had already taken many of our possessions. But that morning after the fire, walking through what remained of our house, I stared at the gaping charred hole that had been the ceiling, where the fire had shot straight up into our bedroom, which no longer had a floor. I could have been there. Or my husband. Or my two dogs—who would not have known to jump.

But that’s my story to tell.

And, of course, Cocteau, who was a renowned collector of things, was speaking metaphorically, wasn’t he? If we take the statement to its extreme, Cocteau is urging us to purge ourselves of all material things and live only with the passion of our art. But he wasn’t, and few of us do. If your house was burning down and your child was inside of it, would you still choose to save the fire? Cocteau could have set his house on fire. He could have burned all that he’d collected, and lived as a mendicant, carrying only the fire of his art, but he chose not to. He provided us with a provocative phrase only—and, of course, with the beauty and originality of his art.

How do we compare Cocteau’s words with the statement of a Buddhist monk who immolates himself to protest the violence of war? Or with Joan of Arc’s? Both chose actual fire—the unbearable flames of being burned alive— or Cocteau in defense of beliefs that would affect the life-and-death fate of the world community. This literalness of self-sacrifice and passion is what I would hold Cocteau’s statement up against. You can choose the fire, but most often, it’s thrust upon you. And when you’re in the middle of the flames, could you still choose to save the fire, rather than yourself? Not many of us are that brave, except in words.

Among the many things I lost in that house fire was a perfect charcoal drawing of a nude that my now-dead father sketched while he was in his sixties. A sketch about which my boyfriend at the time of my father’s rendering, himself a very talented artist, said, “I’d give my life to be able to draw like that.” So, no, I wouldn’t mind gazing at that picture again.

The artist is constantly grappling with her relationship to solitude and to community. And the truth of her relationship to a statement like Cocteau’s comes not from what is shared at parties or even from what she gains from the healthiest types of community. It comes from her work. It comes from the decisions she makes word by word and day by day. What she keeps and what she gives away and what—when it is taken from her—she can only hope to be able to offer up.