My poem “Southside” was inspired by an amazing book titled Truevine written by Roanoke-based writer Beth Macy. Macy spent years building community relationships and conducting research that would enable her to speak to the particular story of racial pain detailed in the book as well as our community and country’s genocidal history toward African-Americans. The book relates the story of African-American brothers George and Willie Muse, who were basically stolen by the circus in the early 1900s to be freak show attractions and then heroically rescued years later by their mother, who confronted the white power structure of both Roanoke and the circus to get her children back at a time when so doing was very dangerous and difficult for an African-American woman of meager means such as herself. At a time when the Klan was normalized as a civic organization in communities such as Roanoke all across the country.

The powerlessness the African-American community felt at the hands of white people during the Jim Crow era was personified by the urban myth that grew up around the kidnapping, with parents in Roanoke’s African-American community warning their children against being kidnapped by white people, especially when the circus came to town. However, the story reverberates outward and inward to become an examination of the half-buried horror of Jim Crow America and its intimate roots in my own community.

In 1893, as an example of one of the many of thousands of lynchings that took place in America during this time, Thomas Smith was brutally lynched and then burned by the banks of the Roanoke River by an angry mob: Macy describes how “scores of people carried away fragments of Smith’s clothing …[and] hysterical women tore ribbons from their dresses to throw on the funeral pyre.” Macy’s observation that “lynching had almost turned into a spectator sport,” quoting W.E.B. Du Bois’s description of it as “the new ‘white amusement,’” haunted me. And then I came to the image in the book of Smith’s poor body, with the caption, “A Roanoke photo studio sold this picture of Smith hanging from a rope as a souvenir; it was the eighth known lynching in southwest Virginia that year (Anonymous archive).”

The poem about this picture came out in a rush. Its short form and colloquially elongated lines are meant to reflect the straightforward approach I felt to be the only legitimate way to write about the picture. I did not, in writing the poem, want to be another version of the souvenir pusher, appropriating African-American pain and bodies for my own self-promotion. The vulnerability of Smith’s bare feet was a tragic reminder of our shared humanity.

I came across the picture after driving Highway 220 South from Roanoke to my mother’s house in Henry County, Virginia, a drive that takes one through the landscape that was the setting of the Muse brothers’ harsh sharecropping childhood in the Franklin County community called Truevine and, as you go farther south, deeper into the gently rolling Piedmont hills shaped by the enslaved labor that wrested fields from the wilderness. I can’t look at my native landscape without considering this history and how my poor white family lineage was complicit in the inhumanity of Jim Crow America. I do not have any direct knowledge of actions taken by my people as part of a lynch mob, but I do know I come from people for whom racism is a deeply ingrained passion. And I have heard the rumor of a rumor about a distant relative by marriage being involved in something brutal and race-related.

I would argue that most white Americans share some version of this shameful historical complicity with the prevailing racial brutality of the time. We perhaps had ancestors who collected pictures of lynched black bodies as souvenirs or, at the very least, did not fight against the larger society that collected such pictures or, at the very least, benefitted from the social and economic benefits of the violent subjugation of African-Americans. I still see evidence of that subjugation today, in my very segregated city, where affluent white people create beautiful living and cultural spaces for themselves, made possible in no small part from the benefits accrued by years of systematic racial injustice, such as urban renewal, redlining, and school system inequities. I still see evidence of that subjugation in my native land sixty miles south, near the North Carolina border, where slave-made terracing still steps down to the Dan River and where the most prolific surnames in the African-American community can be traced back to the slaveholders. There is, however, some triumph in the fact that very few white people of those same surnames persist.

Therefore, the poem is meant to be an expression of anguish at this history, at the pain and terror witnessed by our soil, our trees, and the souls of shared ancestors. I feel the need to write the name of the man in the picture: Thomas Smith. Thomas Smith. Thomas Smith.

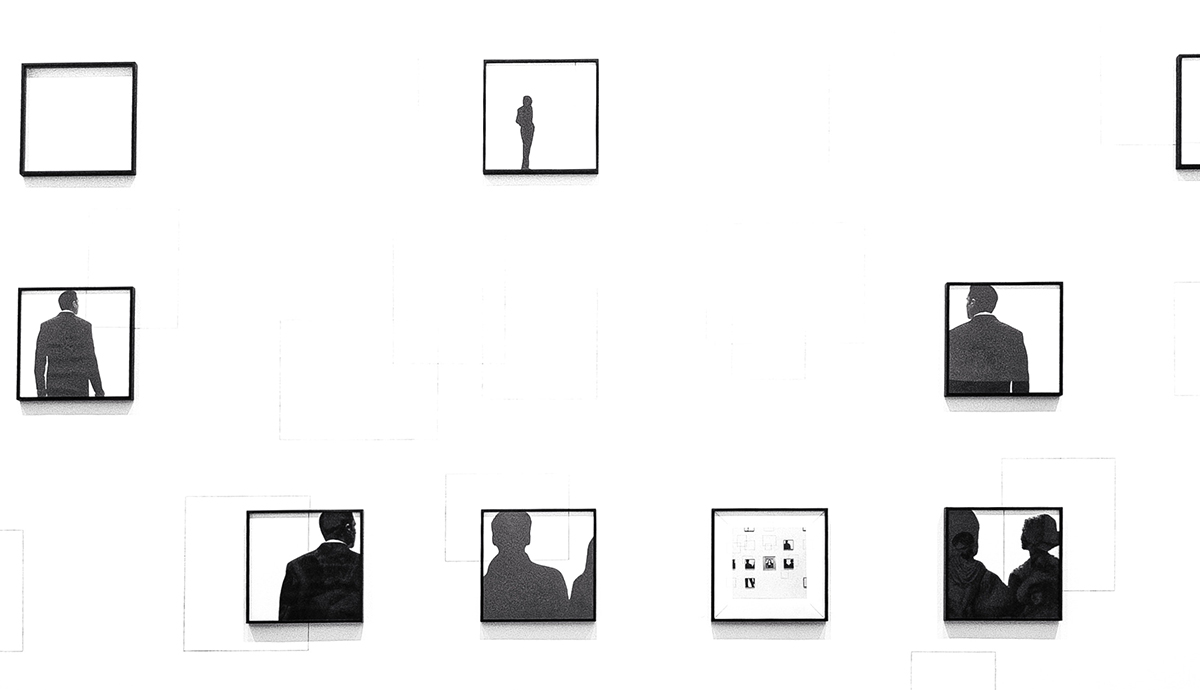

Illustration by Matt Manley. Matt has been working as a freelance illustrator for over twenty years. His illustration is primarily figurative and symbolic with surrealist leanings, and past client work includes editorial, corporate, medical, book, and higher education. Though in the end his work is technically digital collage, the process integrates both traditional and digital media.