NAR poerty editor Rachel Morgan reviews three books; Flyover Country by Austin Smith, The Kindness of Crocodiles by Ann Struthers, and Rewriting the Body by Wyatt Townley. This piece appears in the Synecdoche of Winter Issue 304.1 and we are excited to share it with you online today.

Flyover Country by Austin Smith, Princeton University Press, 2018 paper 113p. $17.95 • At first glance, Flyover Country by Austin Smith uses the Romantic notion of time and space to explore home, but the backdrop of violence and war confounds this reading. Smith’s reach is expansive, as well as his use of form and narrative.

Flyover Country by Austin Smith, Princeton University Press, 2018 paper 113p. $17.95 • At first glance, Flyover Country by Austin Smith uses the Romantic notion of time and space to explore home, but the backdrop of violence and war confounds this reading. Smith’s reach is expansive, as well as his use of form and narrative.

Poetry and nostalgia can easily and carelessly be conflated, and while poetry often traffics in memory, or rather re-memory, poets might balk at the wistful part of nostalgia’s definition. Yet, Smith draws on his childhood home in the heartland for an extensive look into how memory unfolds into the present and confronts sentiment and tenderness in storm-swept landscapes and cobwebbed basements. Family heirlooms, dead dogs, who “become what / They long for: bones,” and Santa visits populate this mostly rural landscape. Like childhood, the independent family farm and small Midwestern towns are also a thing of the past, so to revisit them means “leav[ing] / The highway and tak[ing] / The way of wheat.” The first poem in the collection, “To Go To Lena,” admonishes the reader that the present is also painful: “Downtown, where Main Street / Stretches out like an arm gone / White from the tourniquet.”

Smith pushes pastorals, addressing the influence of humans on their environment. Monsanto and “ag runoff” appear, but most hauntingly, in a rural Wisconsin bar there are “tree-sized men” in camo playing euchre below “The heads of deer, / Their glass eyes staring / Through years of dust /At the men who had killed them.”

To focus solely on its regionalism is to not see the collection’s expansiveness. Poems explore Nietzsche in a moment of empathy and Chekhov contracting tuberculosis. In fact, Smith artfully arranges the poems so that juxtaposition is an additional commentary; for example, “Elegy for Thomas Merton” precedes the poem, “Premature Elegy for Claude Eatherly,” the weather reconnaissance pilot who called “all clear” prior to the Enola Gay dropping the first atomic bomb. Peace and war, Smith reminds us, exist simultaneously.

The succinct poem “Three Radios” traces the generational location of a family radio that announces the bombing of Pearl Harbor, JFK’s assassination, and 9/11. The collection probes America’s repetitious cycle of war and violence. There is domestic flyover space, peppered with farms and windbreaks, but there’s also the long history of American wars and pilotless drones rhyming with “condone” and “atone” that deliver anonymous violence to spaces beyond the safely domestic.

Flyover Country knows what it means to live in a land settled by the notion of freedom by violent means.

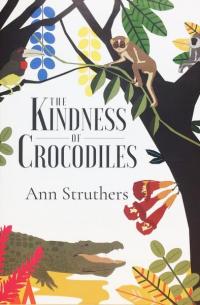

The Kindness of Crocodiles by Ann Struthers, Wild Leek Press, 2018 paper 20p. $15.00 • Ann Struthers’s The Kindness of Crocodiles, winner of Wild Leek Press’s Inaugural Chapbook Collection, brings awareness to the animals of Sri Lanka, and Candace Butler’s colorful dust jacket recalls the delightful work of illustrator Eric Carle—a gray lemur perched among green fronds stares at the reader. These poems are a safari where the reader encounters the “velvet approach of leopard paws” below the “moon’s raw rind” and gray langurs “leap” among trees disappearing like “old griefs” “or the ghosts of all those old teachers.” Hauntingly, many of the animals are viewed in captivity or as tusks made into a temple. Struthers knows this collection is just as much about the animals as about the interference from man. The Kindness of Crocodiles is a modern bestiary that delights and challenges the reader, lovingly designed and printed with a letterpress cover.

The Kindness of Crocodiles by Ann Struthers, Wild Leek Press, 2018 paper 20p. $15.00 • Ann Struthers’s The Kindness of Crocodiles, winner of Wild Leek Press’s Inaugural Chapbook Collection, brings awareness to the animals of Sri Lanka, and Candace Butler’s colorful dust jacket recalls the delightful work of illustrator Eric Carle—a gray lemur perched among green fronds stares at the reader. These poems are a safari where the reader encounters the “velvet approach of leopard paws” below the “moon’s raw rind” and gray langurs “leap” among trees disappearing like “old griefs” “or the ghosts of all those old teachers.” Hauntingly, many of the animals are viewed in captivity or as tusks made into a temple. Struthers knows this collection is just as much about the animals as about the interference from man. The Kindness of Crocodiles is a modern bestiary that delights and challenges the reader, lovingly designed and printed with a letterpress cover.

Rewriting the Body by Wyatt Townley, Stephen F. Austin State University Press, 2018 paper 95p. $18.00 • NAR contributor Wyatt Townley’s sixth book, Rewriting the Body, is a frisky and ardent exploration of the body in both its meanings: flesh and a collection of texts. Drawing from Whitman, Townley celebrates the body from its feet to its capabilities. The last and standalone sentence in Townley’s bio reads, “The confluence of poetry and poetryin-motion has shaped Wyatt’s life,” and “poetry-in-motion” is a perfect descriptor for some of the concrete poems that swirl around the page with repetitious lines, “to the curve of our bones / to the curve of the earth / to the curve of our breath.” Lines circle and revisit, particularly in several villanelles that appear throughout. In the poem “Nothing But Everything” Townley riffs on a refrain that illustrates poetry is inquiry and study: “Will it be good or bad—the news/…/with nothing but everything to lose?” closing with, “Neither good nor bad, the news. / Everything but nothing to lose.”

Rewriting the Body by Wyatt Townley, Stephen F. Austin State University Press, 2018 paper 95p. $18.00 • NAR contributor Wyatt Townley’s sixth book, Rewriting the Body, is a frisky and ardent exploration of the body in both its meanings: flesh and a collection of texts. Drawing from Whitman, Townley celebrates the body from its feet to its capabilities. The last and standalone sentence in Townley’s bio reads, “The confluence of poetry and poetryin-motion has shaped Wyatt’s life,” and “poetry-in-motion” is a perfect descriptor for some of the concrete poems that swirl around the page with repetitious lines, “to the curve of our bones / to the curve of the earth / to the curve of our breath.” Lines circle and revisit, particularly in several villanelles that appear throughout. In the poem “Nothing But Everything” Townley riffs on a refrain that illustrates poetry is inquiry and study: “Will it be good or bad—the news/…/with nothing but everything to lose?” closing with, “Neither good nor bad, the news. / Everything but nothing to lose.”

Located deep in the body, images of longtime lovers curled in a bed, the “secrets of knees,” nipples that have “had enough /of the backs of things— / bras, the insides / of hands and mouths” revel in the delight of long partnership and romance. These poems are also in relationship with the land—a windswept plain dotted with porches and old farmhouses. Calling on Donald Justice’s poem “Crossing Kansas by Train,” Townley’s poem “Driving Kansas,” narrates the seemingly changeless Midwestern landscape that appears between telephone poles: “What sticks up / sticks around. / Grain elevator, water tower, steeple. / elevator, / tower, / steeple.”

Rewriting the Body reflects deeply on the places we inhabit: be it land or anatomy, and lauds all stages and notions of bodies; youth, the aging body, the written, and the recorded.