When I moved to the west coast over two decades ago, the first denizens of the California landscape to appear in my dreams were trees, not people: blue gum eucalyptus feathering the hills where a marine layer rolled with lush winter rains, greening the turmeric-colored brush otherwise ochraceous and dangerously arid during the peak of fire season. As a bicoastal resident of two coasts, I was raised in New England almost two hours east of Emily Dickinson’s hometown. Trees and hills dot the Berkshires, too, but not eucalyptus, and not the menthol-laden scent of eucalyptus after rain. I grew up with the aspens, maples, and birches of deciduous woods with the evergreen firs of northeastern forests.

Blue gum, fever tree. I’ve heard it said a sojourner or immigrant has adopted a new place as home once the terrain enters the heart, in other words, when it appears in a dream. The eucalyptus trees surfaced in my subconscious after one year, fringing the Oakland fire hills where Maxine Hong Kingston’s manuscript, the sole copy, burned to cinders. This manuscript was later resurrected at The Fifth Book of Peace, rebirthed through community writing groups alongside her work with veterans living with post-traumatic stress disorder. Not conversely, years after immigration, ancestors in my bloodline mention the emergence of their birthplace, Taiwan, in their dreams. The capital city of Taipei surfaces at night in street noises, peony-laden heat, and the monsoons of a childhood where small gardens overflowed with wax apples, mangoes, and guavas into a setting of urban industrialization, a city where my mother’s girlhood home, a turn of the century Japanese house with a traditional genkan for removing shoes–and rooms divided by washi of mulberry paper–was unceremoniously demolished to make way for a high-rise.

Green figs, black figs. I blessed my first dwelling in northern California with fragrant oils from a shop that started out of boxes on a sidewalk and exists to this day in a storefront, almond oil with essences named after rainfalls–monsoon and virga–and flowers-jasmine or ylang ylang. Later, I named essences I blended at the scent shop on Shattuck Avenue after female philosophers - Simone Weil, Yoko Arisaka or Chinese dynasties ruled by women–Zhou, of course, ruled briefly by Empress Wu whose royal yellow dress code modulated out of a vast network of spies she employed, ruthlessly, in her rise to power. If I recall my history lessons correctly, Wu Zetian was the only woman who wore yellow, the emperor’s color, in a sound-play of homophones: emperor is huangdi, and yellow is huangse. Transliterated into English, the paranomastic play is all the more evident: huang and huang, although represented by two different ideographs in Chinese, yellow emperor. This power-driven empress regnant’s talent at jotting little odes with rhymed couplets, a tonally regulated form considered a fresh style back then, is eclipsed by the political intrigues and violence clouding her court.

Ozone-spiked ether of aerosols, the California sky bore witness to a torrid, incandescent wilderness of brushfires. On the fourth floor, when I stood on a kitchen chair, a dim blue margin hovered at the skyline, our San Francisco Bay. To the south, a slender eucalyptus higher than the four-story roof stood sentinel in the yard, shedding plentiful salmon and avocado-colored bark carpeted by sickle-shaped leaves cooling the air with menthol drops after rain. The tree dropped countless nuts smaller than acorns. If you picked one, a hint of bluish verdigris–a bit like lichen–was the blue gum. Blue gum eucalyptus. I learned eucalyptus was not native to California, but rather, Australia, carved into boats and oars on it’s southeast coast, and lethal in the hills during the fire season, potent as dry fuel, paper torches waiting to ignite.

A surprising benediction at the end of my first year, it rained heavily in winter–El Niño, warm and sympathetic in contrast to the freezing downpours on the northeast coast. Strawberry Creek rose out of its bed on the Berkeley campus. Rain gutters unsuited to torrential waters flooded sidewalks as my writing, in turn, evolved with the weather: line breaks surfaced in my prose. When I lived in New England, I wrote fiction throughout my girlhood and adolescence–vignettes and lyric novellas with sparse dialogue. I’d write through winters of sand-slashed streets, waiting for the frozen slush to change into mud when May offered purple crocuses with cups of saffron, and green maple flowers lured one new bee after another, until all the young bees glinted like new coins, shining honey-gatherers in flight after a long winter. When I moved to the west coast, I wrote poetry: break lines, not hearts became my dictum. I persuaded myself that I had never fallen in love and would not, taking the twenty-third verse of the fourth Biblical proverb seriously. "Above all else, guard your heart, for it is the wellspring of life."

When I moved south on the coast, I made Santa Ana my home before moving to San Diego, and winter–if one might call it winter–vanished in January, when gigantic hybrid tea roses flourished profusely in the arboretums of the Huntington Library. I mistook a votive flame in a window for a bright bud in a thundercloud plum tree. In coastal offshore winds long after the downslope Santa Ana winds passed beyond a fire advisory, I counted seventeen new plum flowers unfolding on the tips, all of which miraculously appeared overnight. Did the flowers exist only in my imagination?

Or were they figments of a dream? Green figs, black mission figs. No, as the four-o’clock birds–flycatchers–arrived later in the day, I woke. In the late afternoon, they settled in the branches and poked their beaks in the dark red-violet center of each bloom. When the birds took their pleasure in this way, the flowers disintegrated and carpeted the grass with their petals. When the thundercloud plum bloomed again with a vengeance, the rest of the tree stood bare except for the flowers weeping their snow-petals onto the lawn. A rare California snow is a blossoming thundercloud plum at four o’clock in the afternoon.

Why do the birds pick apart the flowers instead of eating them whole?

This reply came to me from a woman who is visually impaired, a dear friend who refers to herself as blind, yet sighted concurrently, referring to a paradox of divine insight operating beyond the boundaries of a body. I can see in the spirit, she says. I cannot see as far in the flesh. I see the birds are eating close to the bone. It’s where the flower is sweetest and most tender. Startled by the sight of birds letting an entire flower go to waste, I grasped that whatever existed at the dark red center of the flower – in a state of bliss, perhaps nectar-drenched insects–was close to the bone. This is the nature of dreaming.

Like prayer, it lingers close to the bone.

One night, in early June, I dreamed that I drove clear across the continent to New England, granite stronghold of green hectares and goblin knolls of my girlhood. I would never do this in real life, because I get lost easily, turnpike to turnpike: it takes quite a while to learn new routes, especially long distance runs with a lot of turns. For this road trip, a map of freeways showed inlets, islands, and a series of peninsulas named for women poets. Anne Sexton, Emily Dickinson, Anne Bradstreet. Each stop on the road trip, the guidebook explained, hosted a garden of flowers each poet loved best, highlighted as such in her writing. Did either Anne ever write about flowers, and if so, which ones? In the dream, I couldn’t remember. I knew Emily did. Lilies, trillium, violets, irises in an herbarium of tenderly pressed and dried flowers. In real life, I’d read Sexton and Bradstreet but not widely enough to know offhand. Guests would stroll in these roadside gardens and read poetry broadsides near the flowers, a delightful touch for a rest area. I told the blind woman about this dream, and she said, one day, you’ll plant gardens close to the bones of women poets who are still with us today. Our sweetened, ancient earth, warming by nearly half a degree per century, will blossom close to their bones unless the oceans recede before then.

DEAR MILLENNIUM, BLOSSOMING CLOSE TO THE BONE

Monsoon and virga, jasmine or ylang ylang,

blue gum eucalyptus. Did the flowers exist

only in my imagination? Green figs, black figs.

The rare California snow is a thundercloud plum

at four o’clock. Birds are eating close to the bone.

This is the nature of dreaming. Like prayer, it lingers

close to the bone. Did either Anne ever write

about flowers, and if so, which ones? Plant

gardens close to the bones of women poets

who are still with us today. Our sweetened,

ancient earth, warming by nearly half a degree

per century, will blossom close to their bones

unless the oceans recede before then.

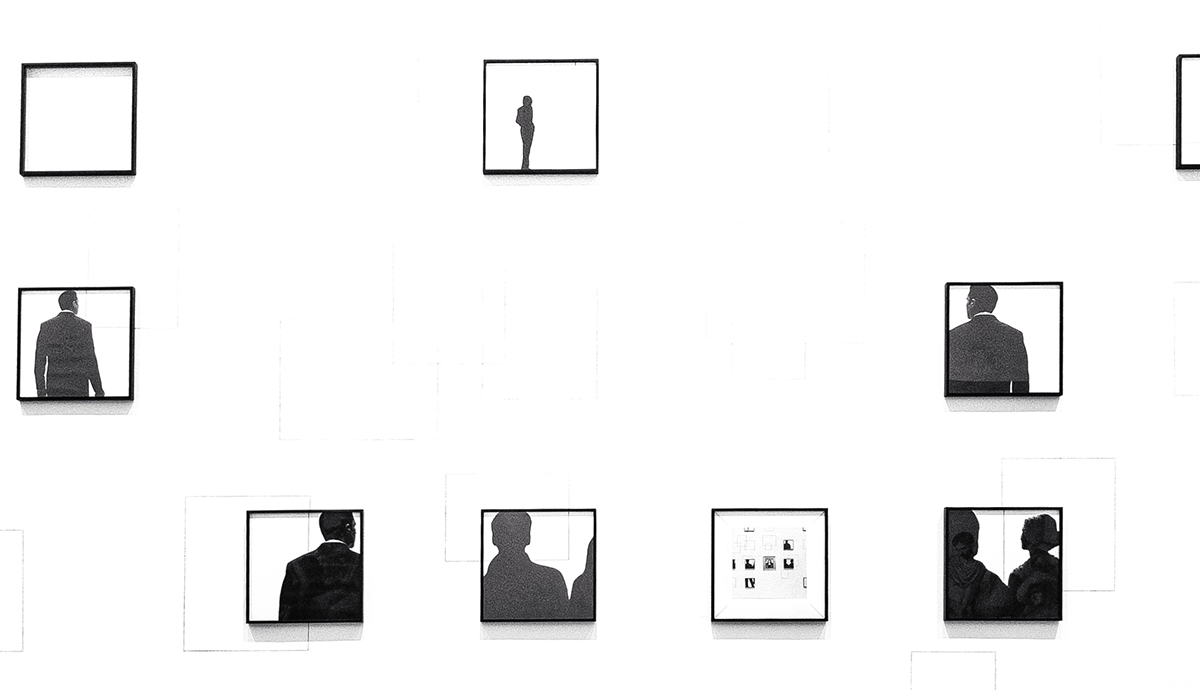

Illustration by: Hokyoung Kim. Hokyoung Kim is an illustrator living in New York. She likes to watch movies and games and enjoys making images with moods and narratives.