Introduction to Every Atom by project curator Brian Clements

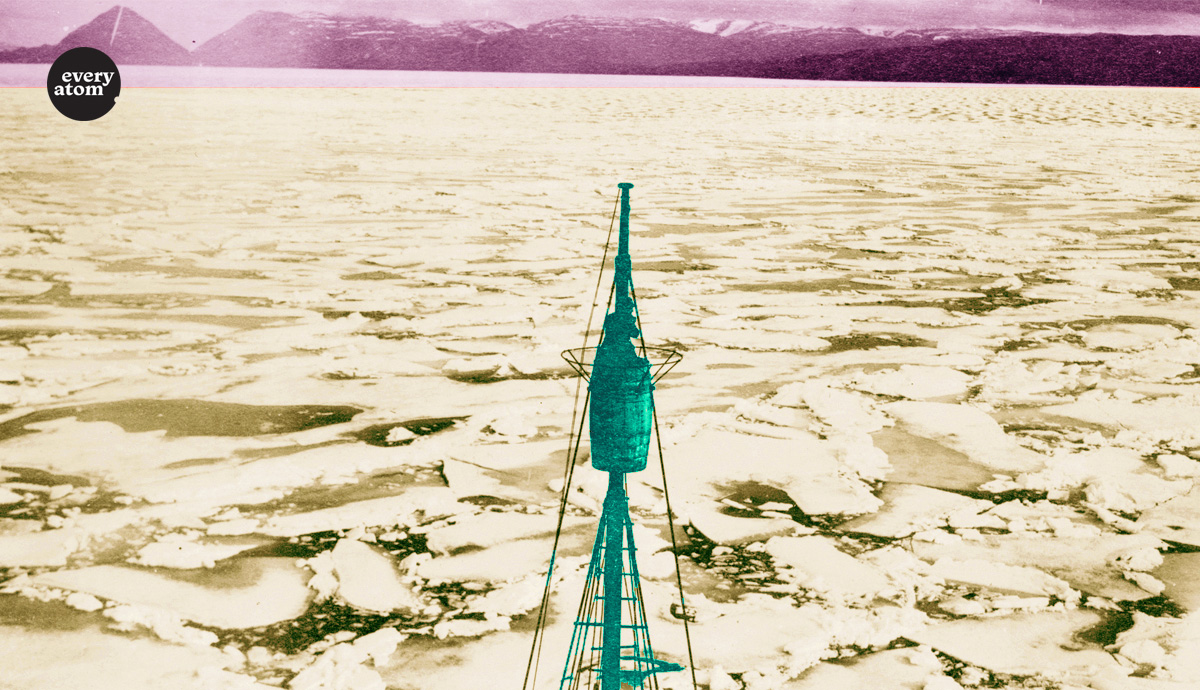

This passage, describing an icescape under the sun of a northern midsummer night, embodies the hopes Americans associated with the Arctic in the mid nineteenth century. Mass culture enthusiasm for the Arctic had reached a fever pitch by the 1850s in the wake of several well-publicized commercial and scientific expeditions. When the scientist Elisha Kane published his Arctic Explorations, an immensely popular account of the second Grinnell Expedition in 1855, the same year as “Song of Myself,” it was said to have joined the Bible on “every parlor table in America.” Likely drawing from Arctic narratives like Kane’s, Whitman imagines seeing the far north’s frozen scenery from a crow’s nest of a sailing ship. For Americans of the time, the Arctic was not so much a place but a passageway: the fabled Northwest Passage, the shortest route between the North Atlantic and Asia. To envision the beauty of Arctic seas passing by was to imaginatively extend the global reach of national commerce. Despite its wonders, Whitman’s imagined landscape is also one of emptiness (“the scenery is plain in all directions”), recalling the fact that Arctic expeditions were liable to end in failure. The Northwest Passage remained myth during Whitman’s lifetime, and its pursuit was associated most often with bodily disappearance—men lost, or worse, devoured in desperate acts of cannibalism (most famously, the British explorer Sir John Franklin and his crew, who disappeared in 1845). In today’s warming Arctic, the Northwest Passage—a once treacherous and enigmatic stretch of sea—is poised to become a major commercial shipping route due to melting ice. The globalizing dreams of mid nineteenth-century Americans has finally been realized, though only at the cost of the Arctic landscape that so enamored them.