I worked for a decade as a biologist before coming home to fiction writing, and as a result many of my stories drink from the spring of science. I love the richness of this subject matter and how it naturally lends itself to gravitas; I love the texture of scientific papers, and science’s innocent assumption that life is ultimately understandable.

However, using this material presents a challenge. There’s the temptation to blurt out jargon: “The scans are matching the frequency of our photon phaser beams! Cloaking device activated!”

It’s also so easy to overwhelm the story with exposition. Andrea Barrett weaves scientific fact into her stories as though it were no more complicated than the weather, but I’m no Andrea Barrett. So I’ve been paying attention to story forms that lend themselves to incorporating scientific information.

One form that has particularly intrigued me is the “hermit crab” form: you take the shell of an existing form, like a recipe or a how-to, and you repurpose it to your own ends. Lorrie Moore’s “How to Become a Writer” is a classic of this genre. I’ve done it successfully with a mock scientific paper, complete with citations and made up Latin names.

A “shell” that works especially well for fiction about science is the guidebook. Karen Russell’s story “St. Lucy’s Home for Girls Who Were Raised By Wolves” uses a handbook shell to tell the story of a teenage daughter of werewolves who has been sent to a Jesuit school to be taught how to act like a human, complete with gloves and shoes and dance steps. Russell structures the story around excerpts from The Jesuit Handbook on Lycanthropic Culture Shock: the stages of cultural assimilation. There are five stages and five sections, and the story follows the girl’s painful assimilation; of course it is a story of change and loss (“our parents wanted something better for us…we didn’t know at the time that our parents were sending us away for good. Neither did they.”) It is a beautiful match of form to function.

Another take on the guidebook form is Patricia Hackbarth’s story, “A Brief Geological Guide to Canyon Country,” which first appeared in the Georgia Review (Summer 2001). A woman pays an open-ended visit to Moab, Utah, to recover from the end of a love affair and the sudden death of her father, and meets another wounded soul, who is recovering from the death of his toddler daughter and the end of his marriage. The story follows their tentative friendship in six sections, each starting with a definition from what reads like a geology textbook (anticline, arch, cap rock, etc.). The story opens, for example, with this:

Anticline: An upward arching of rock strata caused by pressure from underneath, which severely fractures the upper surface and promotes erosion.

And then, without explanation or excuse, Hackbarth launches into her story:

When my father returned from North Korea in 1951, long before I was born, he didn’t go directly home to the family in New Hampshire that was so anxious to see him safe and sound. Instead he stopped off with one of his army buddies in Moab, Utah. His friend’s father was living in a trailer there and mining uranium, hoping to get rich. The two young men spread out their army blankets on the cramped floor at night, and went exploring in the wild and strange landscape during the day, hiking and hitching rides.

My father, a famously silent man, never spoke of what he saw.

The guidebook excerpts place us on location: she’s not just staying in a crummy motel, she’s staying in a crummy hotel in Moab, Utah, next to some of the most spectacular scenery on earth. But they also carry emotional weight. The definitions are all about pressure and breaking and fracturing and, juxtaposed against the largely silent struggles of these smart but inarticulate characters, clearly reveal the pain and pressure they are under.

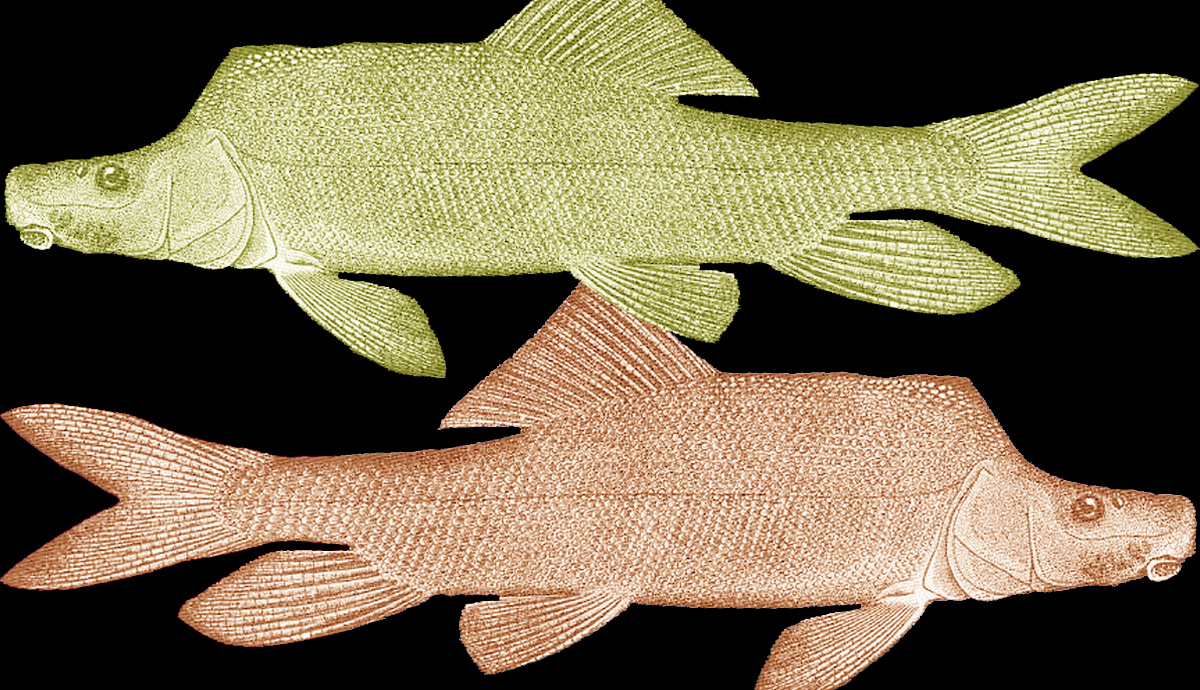

I decided to try my hand at a hermit crab story structured around a guidebook. Ever since I learned in college that the Colorado River has four endemic fish, all of them endangered, I have been struck by the metaphoric and structural possibilities of this fact. A mock guidebook seemed like an obvious way to use this material, especially since I wanted to highlight the expository detail of the fish. I was going to have to describe each of them in order to honor my idea, and the guidebook form gave me a reason.

But the guidebook format also presented a challenge: it had the potential to be static. I was going to describe four similar-looking organisms; there was no natural progression (unlike the stages of lycanthropic culture shock) or deliciously resonant geologic definitions. I knew I was going to need a strong narrative arc in order to overcome that stasis.

I also knew I was going to have to massage the descriptions of the fish so that their metaphoric potential would emerge. Thus, playing around with my central character, a middle-aged fish biologist who has left her family to pursue her fish-saving dreams, I came up with this:

Colorado pikeminnow. Ptychochelius lucius. Slender, cylindrical, with an endless body and a long, pointed snout. Once so abundant it was the poor man’s meat, it was devastated by dams and invasive species. Predicted to go extinct in my son’s lifetime but, as it happened, outlived him.

Bam. I had my inciting incident, and I’d slipped a few mood-building adjectives into my otherwise scientifically accurate fish description. Now I had to figure out what this revelation meant and how it would affect my narrator, and I had four fish in which to figure it out.

The opening about the Colorado pikeminnow clearly had to start the piece. There were other reasons to start there: it’s the most abundant fish, both historically and now, and it made most sense that this was “her” fish, the one she studied for her master’s degree, the one that paid her salary. In this opening section I establish the situation, which is that while she loved her son and her husband, she couldn’t bear to be away from the river and, as the story opens, is dealing with the fallout of having left them two decades before, when her son was a preschooler. He never quite forgave her for this, and, as the story opens, has recently died.

The two middle sections begin with the chubs, the bonytail, and the humpback.

Bonytail chub. Gila elegans. A large cyprinid fish of the Colorado river, growing up to two feet long and reproducing rarely, if at all. Like most desert fish, it is dark above and pale beneath, hidden in both directions. Tail so thin and bony that even nine-year-old Max could grab one in his hand and hoist it from the water.

The second section explores the roots of the conflict between mother and son: he wasn’t the son she wanted, and she wasn’t the mother he wanted. Returning to the scientific theme, she reflects on how this group of fish has a sensory organ that no other animal on earth has. “It’s like I sensed the river with an organ that Max did not possess,” she thinks, trying to explain to herself how they could be so different.

Humpback chub. Gila cypha. Evolved to swim the fast waters of the desert river and specialized to breed only in water warm to the touch. Possesses a distinctive swollen hump just above the head. Almost entirely scaleless; back is greenish gray, sides silver, belly white.

In the third section, when Max is an adult, the two finally confront each other and are able to start to work toward a reconciliation—“in the end,” she tells us, “Max and I almost made it.” Then he is killed in a car accident, and she is left alone with her regret.

Razorback sucker. Xyrauchen texanus. Distinctive flat bottom and humped back; will grow to a meter long and look like it swallowed a boat. Oliveaceous brown above and pale yellow beneath. Smooth. The razorback was Max’s favorite fish. Even on the sulkiest days of his teen hegemony, he would pop up in a moment if we had a razorback in the nets.

I knew I had to end with the razorback sucker, the fish that is the weirdest and the most endangered of them all. I knew this had to be the fish over which they bonded. And then, as I was doing research for the story, I stumbled on piece of terrific news, both ecologically and literarily speaking: razorback sucker populations have rebounded in the past few years, thanks to better river management. The story ends with the sharp misery that she finally has good fish news to share—and there’s no one to tell but his grave.

The story worked—I ended up with a successful piece that won the Conium Review’s innovative fiction prize in 2018 and was published this past December—but I wondered: what was brought to the table by this whole process? Was it just a fish-facty-gimmick? Or did this approach have inherent value?

I decided yes. First, the restriction enhanced the story and brought out resonance I didn’t know it had. The approach also revealed the emotional and metaphoric power of the facts themselves; and this is a discovery that can transferred.

We live in an expository age; poetry no longer has much place in our lives. But exposition—the endless sea of information that surrounds us, yammering on about everything from razorback suckers to copy machines to the structure of parliamentary procedures—is itself poetic. And as it hums along in the background it reveals something about who we are and what we value. And by including that material, which plays on a frequency just below the level of awareness but resonates and reverberates throughout a character’s life, a story can augment its reach.