Introduction to Every Atom by project curator Brian Clements

Walt Whitman first published these lines in July 1855, at the age of thirty-six. He died in March 1892, at the age of seventy-two. So it’s fair to say that “Song of Myself” is both a masterpiece and a midlife crisis in action.

Asked the Sphinx, What walks on four legs in the morning, two in the afternoon, and three at night?

Man, Oedipus answered. Or, as Whitman envisions the arc: span of youth; manhood; dying days!

O rubber band stretched out one too many times! O weight of carrying one’s florid manhood! Get this man a convertible sports car.

But where the poem sings is not in its bombast but in its interpolations, the asides and digressions of the man within the ego. The speaker feels suffocated by his loves—not “loves” in the solely erotic sense but his affiliations, his commitments, the small insistences that in order to make change in the world, he must allow himself to be changed. In nimble imagery these loves come alive, “swinging and chirping.” The gesture of “Bussing my body with soft and balsamic busses,” using the archaic word for kiss, becomes at once affectionate and needy. Haven’t you ever wanted to say, at the offer of a handful of heart, “thanks but no thanks”? The effusions of the world are at once its greatest gift and too damn much to handle. This, too, is midlife speaking.

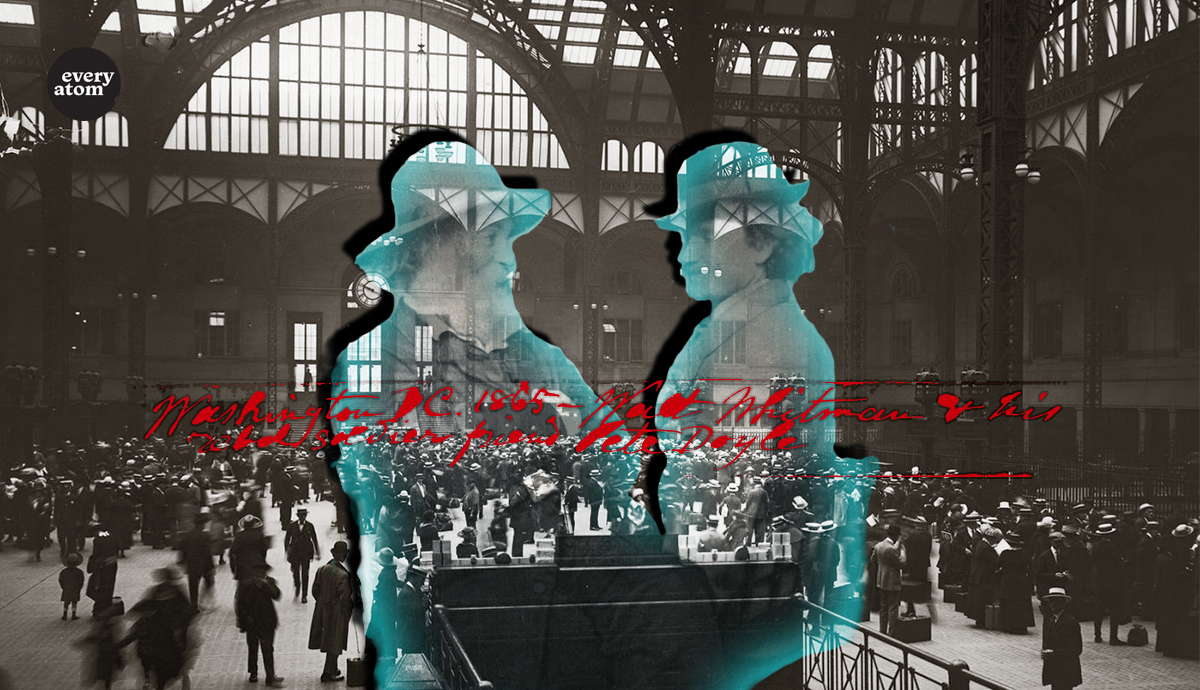

I am in my twentieth year of re-reading Leaves of Grass. When I was a college student at the University of Virginia, we huddled around pages that showed Whitman’s hand-edits in pencil to the “Calamus” section of later editions. When I moved back to D.C., I came to understand how poems such as “The Wound-Dresser” were shaped by Whitman’s time in Washington. A poem is made great not by the answers it provides, but by the questions it causes you to ask yourself. Every time I return, I ask a different question. That’s the power of this magnetic, maddening, capacious text.