In Burning Down the House Charles Baxter defines stillness as a pause effect: forward, narrative movement ceases and protagonists are absorbed in the minutiae of setting, caught up in moments of awe and odd wonder.

The outer story line stops for the inner story’s reflections.

For crime writers, stillness may occur when the narrative slides sideways, and the plot stills for character development.

This is what Ed Lacy does in his Edgar Award–winning novel Room to Swing published in 1957.

Lacy’s novel features Toussaint Garvey Moore, a Black private eye from New York, framed for murder, who travels to Bingston, Ohio, a Midwestern-Southern–type town bordering on Kentucky, to follow the only lead he has, a name, May Russell.

Lacy, a New York intellectual, a liberal, and a white man married to an African-American woman, loads his novel with layers of social injustices. In the opening scene, Touie is racially profiled by a white cop, harassed for being a Black stranger in a largely white town. The cop repeatedly calls him “boy.”

Chapters two to five establish Touie’s backstory and the murder frame-up. Lacy explores a Negro’s experiences by unveiling a series of white and black faux pas: a group of liberals at a party expect Touie to be an expert on the “Negro question”; Kay Robbens, who hired him, paws at his muscular body as if he’s a “horse”; and as Touie tracks Robert Thomas, a New York beat cop takes him aside and advises, “welding school . . . Good trade to learn.” Black men are given little room to swing in 1950s America. Even Touie’s girlfriend, the light-skinned Sybil, objects to how dark-skinned Touie is and wants him to define himself within socially accepted parameters: take your civil service exam and become a postal carrier, she advises. Touie wants to go into private practice as an investigator.

Eventually, Touie is lured into a room where he discovers bloody pliers and Thomas sprawled across a bed with his head bashed in. Touie punches out an overzealous cop and makes his escape. He later comments with cool sulky languor: “I’d committed a greater crime than murder—I slugged a cop.”

But it’s in chapters six and seven where the narrative pauses, the action line slips into character- driven complexities. The prose, no longer full of broken glass, shapes itself around structural redundancy, as four times similar stories are told about the late Robert Thomas, aka Porky.

Mikhail Bakhtin in his groundbreaking work on the Dialogic Imagination praised Fydor Dostoevsky for refusing to finalize his characters around single truths. In Chapters six to seven, Lacy does a similar move with murder victim Robert Thomas.

Earlier, in the New York section, Thomas gets into a fracas with Touie in a bar. Thomas calls Touie a “damn nigger,” takes a swing at him, and Touie twists the blond kid to the ground by wrenching a hand behind his back. “If you get up, kid, you’ll get hurt,” he warns. Thomas backs off. It’s a simple scene, that works to finalize Thomas around one truth: a bigoted, dislikable punk-ass.

But in Bingston, with Touie chasing down the story within the story, the action line stops and Lacy deepens the novel’s exploration of hardscrabble whiteness.

Four different speakers complicate the Robbie we had finalized as reprehensible.

First, there’s Frances’s Uncle Jim. Frances is a young Black woman helping Touie in Bingston. Uncle Jim tells the private eye that he knew Porky when they were kids and after Jim punched him out, “he wasn’t no trouble.” Jim empathizes with Robbie: “He wasn’t real bad. A white kid like Porky, he ain’t got nothing.” He stole eggs to survive and he’d share his smokes with Jim and they’d “shoot the gas” in the fields. Touie expects to find someone who hates Jim. Instead, the first person he talks to identifies strangely with a white kid: “You say he’s dead. Jeez.”

Second, there’s Tim Russell, the brother of May, a white fella who grew up dirt poor, and has since made something of himself. He corroborates Jim’s story: nobody hated Robby “enough to kill . . . He was forgotten more than hated.” Tim, too, felt sorry for him; the kid lived in a shack at the end of town in a grungy section called the Hills. Tim’s own mother died young, as did his dad from alcohol, and he and his sister and Robbie “raided farmers’ fields, lived like animals.” May eventually sold her body to make ends meet. She and Robbie became lovers, and when she got pregnant she accused him of rape to force him to marry her. Robbie beat her “so badly, she lost the kid.” For a time, Tim hated Robby, wanted to kill him even, but “I realized it wasn’t his fault. He’d been as trapped by circumstances as May.”

Tim can’t completely forgive Robbie, but he has compassion, placing Robbie’s bigotry and domestic violence within a larger social context of neglect and want.

Third, there’s Mrs. Simpson, a Black woman who lives out in the Hills, a place full of musky odor, “decay and death.” She tells Touie another story of want: “Thomas slept right in this room, on a mat before the fire. Many is the meal I gave him.”

After Robbie was charged with rape, Mrs. Simpson woke “in the night to find the one window I had was busted.” A drunken Robbie calls her a “nigger,” and then he bawls “like a child” asking, “Ma Simpson can I please have a glass of water.” He even takes out a handful of money to pay for the window. Mrs Simpson tells Touie that after jail, Robbie comes out meaner than before he went in, but “Porky wasn’t real bad. I seen plenty young ones wild like him who settle down to a good life.”

Tim would be one of them.

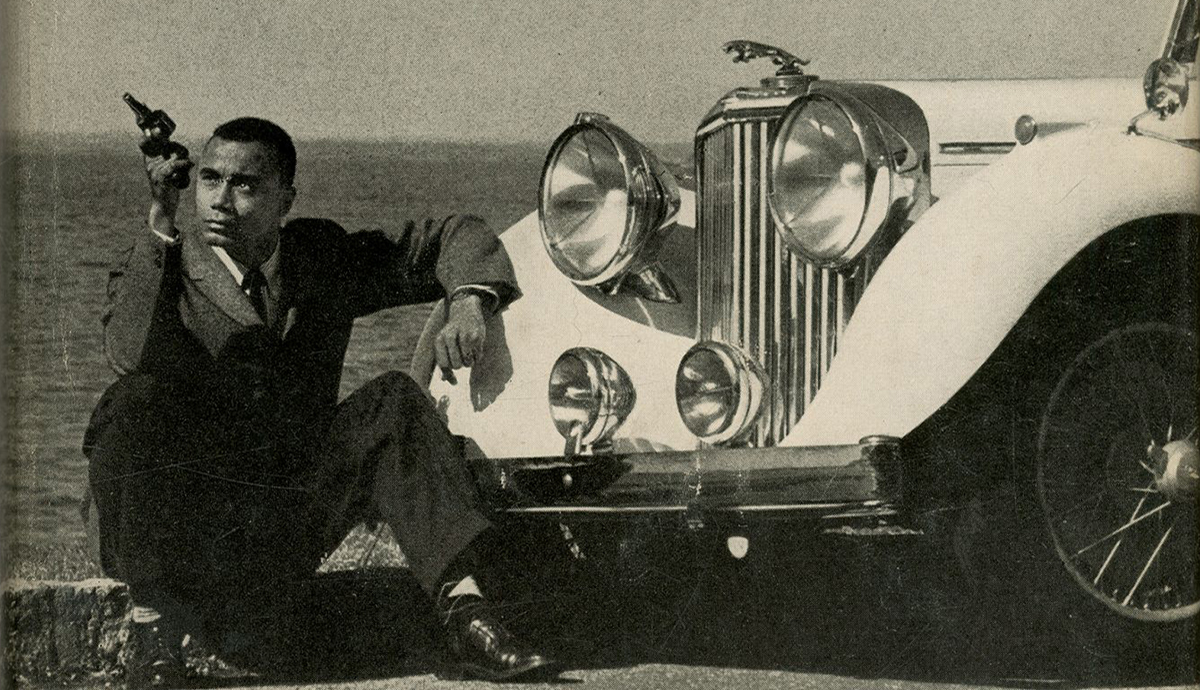

She thinks like a detective, seeing through his first posture (pretending to be a jazz musician) and advises him to lose his souped-up Jaguar.

All three of these stories open up Robbie’s representation, moving his characterization away from nature into a nurture argument: Robbie’s bigotry may be a product of having grown up poor, without privilege and parental guidance, and his being a victim of a punitive justice system that made things worse than better.

We don’t condone Thomas’s actions but we have greater empathy for the context that created them.

Even Touie, upon hearing these stories, comments to Frances, in an almost meta-way: “I came here to find the killer. All I’ve found was that Thomas was a mixed-up kid.”

Film Scholars David Bordwell and Kristin Thompson have shown how neo-classical Hollywood cinema often has two plot lines (action and romance) and often they are separate but on many occasions they dovetail into one another. In Die Hard for example Bruce Willis tackles a group of “terrorists” while also trying to salvage his marriage. When his wife Holly is held hostage by the robbers, the two plot lines (action and domestic) coalesce.

In Lacy’s Room to Swing this dovetailing also takes place. While in the country, Touie begins to question his relationship with Sybil and finds himself drawn to Frances. She thinks like a detective, seeing through his first posture (pretending to be a jazz musician) and advises him to lose his souped-up Jaguar (it’s too conspicuous) and replace it with a rattletrap rust bucket that her uncle Jim loans them. Their compatibility surprises him. As he prepares to confront the killer in New York, Touie “waved to Frances, blew her a corny kiss.” He downplays his feelings for her with a kind of deflective armor (the half-hearted kiss), but as the bus pulls away he realizes the true complexities, perhaps, of their shared feelings: “I looked back and she was waving. In the split-second last look I had, I thought she was crying.”

For Lacy, the country is a place of transformation on the personal and social level. Touie connects with Frances and deepens his understanding of the conditions that informed Robert’s character.

However, Lacy’s stilling of the action line ultimately has to return us to the crime story formula: there’s a killing to solve. With the fourth speaker, the narrative pause effect lifts. Mamie Guy, a Black woman who presses shirts for a living, tells Touie, “Lots of people didn’t like him. But nobody would kill him,” echoing the words of the three other speakers. And then she says that “out of spite and meanness” Robbie stole McDonald’s shirts.

Steve McDonald, a member of the faux liberals back in the early chapters set in New York, who asked Touie to be an expert on the “Negro question.” Steve McDonald, distant cousin, and failed big-city writer of naturalist prose. Steve McDonald, who in the final three chapters will be tricked into confessing and setting Touie free.

Thus Lacy’s novel fulfills its promise to be a crime story. But for two chapters, Lacy gives himself room to swing as a writer, taking us into a frisson-zone with Frances and a holding pattern of narrative repetitions that open up the Thomas backstory into something compelling, troubling, and thought-provoking.