I loved it when I found the coach’s voice because it gives you a hell of a freedom in America, one that I used to have all the other voices in me to come out. I don’t know how it is in other places. I don’t even know how it is in the country of my birth, Iran. But you can’t talk any more American in America than when you talk like a coach, which is partly the inside language of a sport–basketball, in my case–but it’s partly a talking with the understanding of sports as the central fact of life, which I could do, making me immediately accepted by Americans, almost shockingly so, and then once they had come in close like that, that’s when I would smoothly glide over to topics like why in the heck America was always talking about bombing Iran, and I am telling you, they wouldn’t know what hit them. They would hear me talk with the certainty of a man who has thought about the pros and cons of man-to-man versus zone defense, and they would have no choice but to ascribe the same certainty to my thoughts on things in the geopolitical realm.

I would advise anyone who is interested in talking to Americans to consider taking up the coach’s voice, which is also a way of standing and watching young people performing drills–in my case, the eighth-grade girls on the Laurel Hill School basketball team–and connecting their movements with a larger strategy to be employed in the next game. A coach, then, is understood in America to be someone possessing vision, who understands how the details add up to a unified whole. Maybe it’s all the rugged individualism they have here, maybe it leads to an overly romanticized view of sports, as the only place where teamwork and community are valued. I don’t know. I can be pretty romantic about basketball myself. The coach’s voice is sincere, in other words. It’s no act. It just happens that when I am talking to one of the mothers or fathers of the kids about our philosophy around a full-court press, there is a vitality to the conversation that touches our whole lives, and if the conversation shifts towards the history of American interventionism in the Middle East, they might have to acknowledge that there is just as much vitality to the human costs of modern imperialism.

It’s easy for people to think about bombing another country when they think that what is happening there is dead anyway.

It’s not a bad way to go. It’s especially effective if you happen to be winning, which we were doing in the year I’m thinking of. There were mornings then when I would read in the paper about the latest indication that America might be declaring war on Iran, and then by the afternoon I would have to feel American enough to find the coach’s voice inside me, which on the one hand was not American at all, because things I was encouraging like humility and effort and patience and unselfishness are not bound by nationality, but on the other hand the particular form that the articulation of those principles took was deeply American, like nothing I had ever known before. I listened to the words coming out of my mouth and did not know myself that I could feel so connected to a gym and a city and a country by virtue of speaking them. A coach confirms something about a place because they are saying that this is a place worth playing a game in, and that it is a place worth stretching ourselves to play our best in. And then afterwards, I wouldn’t regret anything I’d said when I remembered the news in the morning paper today. I would use it to say–here is why America should not bomb Iran: because something just as alive as our basketball practice is happening there today.

It’s easy for people to think about bombing another country when they think that what is happening there is dead anyway. I just don’t know how those people bring any life to the place they are if they are incapable of imagining it elsewhere.

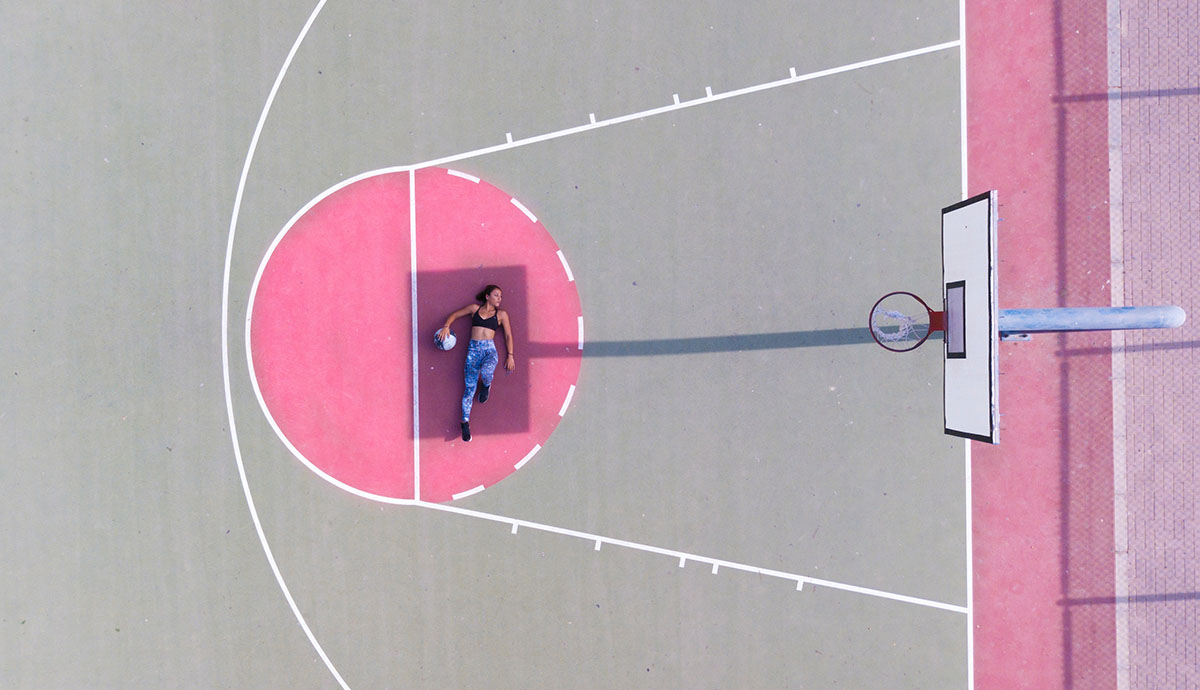

We had a great season that year. Each morning I’d feel a million miles away from America, and then by the end of the day I’d find my way back. I’d find my way back to the very heart of it, summarized in my case by the rhythm of a bouncing basketball, its willingness to come back up after hitting the ground each time, the sound it made in a gym, the feel of it in your hands. The effort to come back to America each day was also the effort to figure out how we could play better as a team. They were wound up in each other. I loved the American language I could use to describe the steps we needed to take to better ourselves, and loving a language always gives you at least a shot at loving a place. I tried to speak in a way that said that our success as a team was the opposite of war.

It was all very funny, because how many coaches have spoken of athletic excellence as something that lines up very neatly alongside the flag and armies and war? Go ahead, I said to all of them. Our defensive effort lines up very neatly alongside peace. It lines up very neatly alongside a kid in Iran not having to worry about American bombs falling on them. That kid was a part of our team, when we thought of our team expansively, which I often did. I tried to think of her as part of our team all season, and I never spoke of her to the girls directly, but I tried to speak in a way that she knew she was included.

If there were Americans at our games who heard me talking in the coach’s voice, who saw me on the sideline at the beginning of the game putting a water bottle under my chair, breathing in the thrill of uncertainty, hoping to reflect to the girls that uncertainty was a gift because without it there was no shot at discovery, if they heard me call out the plays in a voice that was aiming to be confident and humble at once, that yelled only to the degree that it needed to yell to be heard, that sought to temper both the momentary successes and failures because a game, like a life, was long, if they heard and saw all that and concluded from how American the whole thing seemed that there couldn’t possibly be a girl in Iran on our team as well, there wasn’t much I could say I guess except, Listen better. Listen better because inside the words and the language is hope, and I couldn’t have a sense of hope about the team if I didn’t have hope in there being no war, because all hope is connected, so much so that there were some games where I wouldn’t know what to do with all the excess hope that was left over from hoping that there would be no war all day. I’d try to pack all that hope down into a size that seemed proportional to the significance of a middle school basketball game, but then I would remember that there was always room for the overflow because you were alive, and so you were going to need every bit of it. You could bring all of it anywhere, and that was part of the coach’s voice too, the belief that all hope was connected, which was something I had seen in the old coaches I’d had too, it was just that our hope traveled easily to things as far away as war, and I felt good about that before a game because I knew whatever advantage the other team had, they weren’t going to out–hope us. You couldn’t out–hope peace, because when had peace ever worked? When had human beings ever given up on war once and for all? Our hope was ridiculous, and sometimes I would almost feel sorry for the other team if they didn’t know how to hope so ridiculously.

It was ridiculous for us to make it to the championship game, and it was ridiculous for us to win it, but that’s what happened that year, and there was such a soft feeling afterwards that it was the closest I came to telling them about the Iranian girl who had been part of our team all season. I stood before a group of American kids and their parents and I almost told them about the Iranian girl and I wanted to tell them in the coach’s voice because it had a lot of authority by then. I wanted to tell them in the same voice that said Attaway and Good hustle and Defense first and Stay humble and Talk it up out there and Bring it in and One game at a time and All we can control is what we do and Grab some water and Run it out and Stay focused and Get some rest and Let’s celebrate for today and be ready for practice tomorrow and Easy passes and Help her out and Head up when you dribble (Slow with your head up is better than fast with your head down) and Look to trap when we press and Try to force a high pass and Play defense with your feet and Box out and Stay aggressive and Swing the ball around and Hands up and Good screen and Way to play together and Have fun. I almost told them in that same voice about the girl in Iran and how I thought she was a part of our championship win. I didn’t do it though. I remembered how the best part of coaching was letting them discover things for themselves. If there was even a chance of them doing that, it was worth not saying a thing.