Once a week I’m off to the food co-op for the unsweetened coconut yogurt and the pastured cow butter and the eggs from the free-range chickens. For the dead animals that haven’t been tortured before they’ve been slaughtered: the whole chicken and the local grass-fed beef and occasionally the pork and always the ground turkey, a basketful of corpses. It takes a village! A village of livestock and the forests they replaced. It takes dodging any vegan acquaintances one aisle over—no one even takes the vegetarians seriously anymore, all that cheese, but the vegans are to be reckoned with—and scanning for that one cashier who also eats meat, who appears less offended when the salmonella chicken juice drips onto the conveyor belt. It takes sheer labor, generating that can of tomatoes, that five-pound bag of Yukon gold potatoes, the coconut aminos, and that jar of fermented salsa (because fermented foods feed gut microbiota! It takes a universe of billions). The profusion is quantifiable, all those costs of growth, production, sales, and consumption, traced back to infinity. Numbers, boy, I’ve never much liked them. But eating real food every two-three hours, day after day? The numbers are against me in ounces, in pounds, in rinsing, soaking, chopping, roasting, boiling, frying, baking, freezing. They’re against me in calories consumed measured against the time required to consume them—so fast! Nothing short of astonishing, those dishes to be washed.

Purchasing a chocolate treat, and sometimes more than one, motivates me for the weekly errand, the more essential items being inadequate inspiration (spaghetti squash, zucchini, spinach, harrumph). Chocolate forces the task, and who am I to resist the cacao-desiring microbes that chose me and bypassed others, leaving the unanointed to their hard candies, their sour chewy things? A brownie made from almond butter or the refrigerated single-serving dark chocolate torte or the flourless chocolate cookie held together mostly by the eggs. Plus the week’s supply of three or four dark bars at 72%-85%. The cocoa is fair trade, of course. The co-op has product standards, after all, and luxury items will not be enjoyed at the expense of small children in other countries or other species or entire habitats, except perhaps when consumed at an average rate of three ounces per day. And then? Who knows.

I am the progeny of ancestral predator glut, unelected representative of the last generation of absolute indulgence.

Usually a beverage ends up in the cart as well, from the cooler by the café where people sit at a counter against the window squinting at their phones in the setting sun. A bottle of lemon chipotle kefir, most often, in spite of how poorly it pairs with chocolate. All those live cultures! A can of Stevia-sweetened root beer. All that gut-soothing ginger! Or maybe the berry-flavored sparkling water that comes with a task for the imagination: if you believe hard enough, it tastes like berries. Tap water infused with bubbles like you’re some kind of child.

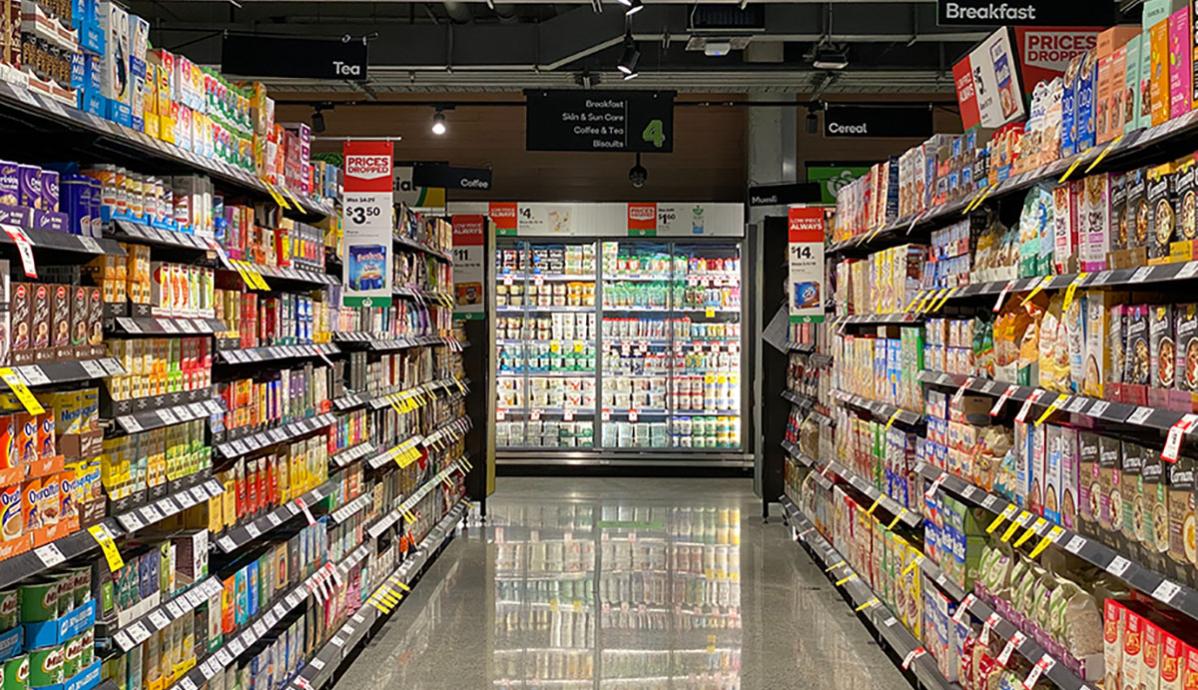

The employees must realize that this small grocery is not in fact an enchanted place to reward all longings, just as those who work at the zoo or the amusement park do. Who even cares anymore about the yawning tigers, the swings that propel you against the horizon line, the blue wide-mouthed mason jars? Who cares about the bins of nuts and seeds and herbs and loose-leaf teas, the rough-hewn chips of marshmallow root and licorice for calming the gut, the bright pink raspberry bits buried in the green tea that builds the mucosal lining? Because once I’ve really savored the tiny scales and the tiny golf pencils and the tiny yellow stickers for labeling the appropriate number of my purchase, am I satiated? No. I swing along a trajectory of fullness to hunger tossed out of my seat and hanging on by the cable, hoping that any minute now the operator has sense enough to slow down this ride.

I can afford these excursions to the food co-op—and also to Kroger, Aldi, Publix, Trader Joe’s, Food City, Walmart, and Whole Foods—by a small but ultimately significant margin, expert forager of the right foods at the right prices in the right proximity to home in order to feed my all-consuming appetite. If the cashier is appalled by the cost of the food she rings up (as I myself would be, except that through years of practice I have stopped noticing), she doesn’t show it. She has no reason to be shocked by the total bill of sale for the people who pass through her line, the mother who interrupts her child’s begging for organic chocolate milk with lessons in agricultural production. “Growing asparagus is actually fairly labor intensive,” she tells her four-year-old as she places the vegetable on the conveyor belt, and I am grateful that I am merely raising my own inner child, feeding my own pet, the beast who lives within and who will not grant me a moment’s peace. I am a hunter-gatherer who inhabits a land of plenty as if she once occupied a region of scarcity, refusing to bear children because there wouldn’t be enough for all of us, always surveilling the landscape for sources of nourishment. I am the progeny of ancestral predator glut, unelected representative of the last generation of absolute indulgence.

In truth, the cashier shows no surprise because she shops here herself, and maybe she’s the one whose wife works at the all-butter-all-the-time bakery and whose child attends the all-nature-all-the-time pre-school, where the children are daily bathed with invisible organisms and with those chemicals released from the trees that cheer them right up. Or maybe she’s the one with the new boyfriend who helps me to find the toxin-free lubricant. I refrain from confessing to her that when I ovulate, as when I menstruate, I could eat all of aisle six—plantain chips, potato chips, cassava chips, bean chips—riding a carousel of progesterone and estrogen. Such cravings interfere with the monthly reminder that on the cusp of the luteal phase, I am in fact capable of sexual desire. Those starches should facilitate a good romp in the hay. What’re they good for, otherwise? Instead, carbohydrate consumption always wins—more eating, less fucking—which heavily underscores the entirely useless ritual of bleeding once a month into late middle age.

For it must be said that I am driven by an appetite that exceeds any reasonable measure, as if the churning microbiome of beneficial and pathogenic and non-binary (thank-you-very-much) creatures residing inside me intend to take down half the planet for my sole benefit, which is to say for their sole benefit, as I am a mere vessel, and I am legion. These inside-outsiders to whom I outsource the labor of gleaning nutrition, collective parasite without whom I could not survive, have somehow grown beyond proportion. I toggle between killing and feeding the bacteria and fungi, and in the killing of them they seem to cry all the louder for their feeding, starvation putting them in a pinch, a panic, as it were, so that I am in a pinch, in a panic, no small portion of the time. This surging of hunger does not, counter-intuitively, unleash all cravings, but instead urges sustenance without specific recommendations. Nothing sounds good. The desires die from utter exhaustion, leaving me hungry in the face of abundance, without a thing to eat.