Recently, I had occasion to attend a poetry reading at a local charter school. The children were exuberant, eager to read their new poems to the audience—so new, in fact, that some of the poems were still being composed as the kids walked up to the stage. There were twelve readers, cute and endearing as the day is long. Their poems were sweet and silly and tender and sad. Strikingly, though, while they were engaged in the process of composing poems, it became apparent that they had not actually read any poetry at all. This is not meant to be disparaging, simply factual; it was confirmed by the children themselves in an after-reading conversation—many of them had read four or five poems, if that, in their schooling career, just as many had only read a handful of haiku (remember we had to that one day in fifth grade? one remarked to another as we chatted). They had been offered time and space and encouragement to compose, a rare and important treat. But their school experience didn’t lend itself to developing an ear for the rhythms of poetry, or an eye for how it looks on the page, or a sense of what a poem can do to a reader. A lot of “outbreath” without “inbreath.” This is a good school, mind you. Parents have been known to lie, cheat, and steal to outgame the admission lottery.

Enough time has been spent (or, never enough time, rather, but still!) lamenting the sad truths of the information age and the danger to the humanities in the era of STEM education. This is apparent to most of us, even those who support the sciences and mathematics. Those in the arts are painfully aware of these facts, especially as we struggle to justify and rationalize the practical and immediate “payoff” for poetry in a consumer culture. What is worth thinking about is the fact that when we receive any art education in school, it feels like such a gift to have time devoted to the cause that how it is being taught is often sidelined. How we think about writing, in particular, represents a much larger question for all of the humanities: how do we (or should we) attempt to impart a sense of aesthetics to a young person? How do we rationalize an education that does not attempt this, or accept one that does so meagerly, just because we are so grateful that poetry and art and music are not dead altogether, swept under the carpet by the last of the night janitors?

In general terms, during the K-12 odyssey, poetry at best is a three week “unit” attempted twice. At worst, it is nonexistent, or the exposure to poetry is reduced to the one-time experience of writing a few haiku, a form taught largely because its brevity eludes its complexity for teachers and students alike. My years of surveying college freshmen reveal that the art of creative writing is not only neglected but positively avoided by teachers and students alike. There is a real sense that poetry is a thing of antiquity in the era of information; the ephemeral nature of a poem seems to elude the impulse to just know what it means. What is the takeaway? What’s the bottom line here? Teachers have little if any time in the curriculum to devote to the subject, and something about the physical dimensions of poetry on the page make it seem like a subject that can be mushed in if and when necessary. Many teachers lament that they themselves had so little training in creative writing that they have no confidence to teach it, and I am told they “just don’t have time” to step back and appreciate the way language works. They gotta diagnose the poem in seventeen minutes before they have to move on. Students, therefore, are fearful of poems, and of composing them. If I offered my college students the choice of reading ten poems a semester and then writing five, or doing a 25-page expository paper on Hybrid Cars or Autism or Drought in California, a surprising number would opt for the paper. There is great comfort to be found in information.

The handful of whimsical teachers who are inclined to delight in creative writing as a worthwhile endeavor often approach it from more boheme directions. I can appreciate this more than its abandonment. There are drawbacks. In my tenure as a Poet-in-the-Schools, I found many classrooms where “nonsense” poetry abounds. Poetry becomes the tramp dressed in black smoking a cigarette out on the blacktop. Teaching her, therefore, invites the muse through alternative means, such as having the children lie on the floor pretending to be dead and writing their own elegies (learned this from a fellow poet, tried it once). There are elements to the varied and light composure of verse that that are absolutely wonderful, if there is some sense of what a poem sounds like. But how does the child who has not been moved by words know how to hear their own song?

I was lucky enough to be a student of Kenneth Koch at Columbia University in the 1990’s. Koch was a supreme advocate for the art of imitation in poetry. Not only did he author several of the definitive guides to teaching poetry in the schools, he also believed strongly in imitation for his own university students. During my time under his tutelage, I wrote twelve imitations; some terrible, some mediocre, and one or two that were memorable. But each involved a careful and concerted study of the writer I was attempting to imitate, with voice, language, subject, intonation. I learned to hear. Like any painting student watching their “master,” they knew that the way to improve one’s work was to study the art of others. Listening was an act of attempting to understand the beauty of language. With the assistance of Koch and the writing program, I was able to spend a year working for Teachers and Writer’s collaborative in NYC. I followed in his example, using imitation as a core component for my classes. Imitation is truly a sort of magic. It is one of the few “applied” approaches to poetry that is somewhat teachable, a doorway into the mysteries of language that a good teacher with little creative writing experience can use. Write enough imitations and you actually begin to hear when Rimbaud stops and your own little yawp begins.

In a humble attempt to bring state university education back to some of its initial “coordinates,” our Honors Program at Chico State recently underwent a redesign. The four required undergraduate courses now required are Beauty, Nature, Truth, and Virtue. Courses are intended to be interdisciplinary, with each seminar taught by a core of 3-4 professors from differing fields, bringing a wide range of perspectives for students to enter the conversation. I have been teaching the Beauty seminar with a colleague from Biology and another from Religious Studies. I want to say that we are aware of the objections to the question of whether or not beauty is the sort of thing we ought to be teaching at all; we were interested in engaging the concept of beauty and some of the philosophical, scientific, and artistic discussions that relate to its study. However, this proved to be an intensely difficult.

We approached the course with the principles of Phil Ochs’ marvelous saying, In such ugly times, beauty is the biggest act of rebellion. The students did not want to rebel much. They were tired from years of K-12 drilling and were ready to do as asked, so long as it was not particularly taxing. The problems of how to approach questions of aesthetics, connections to ethics and morality, the existence of beauty, and the complications of relativistic thinking proved to be more difficult than we anticipated. Explaining beauty—or rather, a concerted conversation about aesthetics, nature, geography, even the beauty of complexity—was nearly impossible. Many of our students grew up in the Silicon Valley, with its abundance of strip malls and press board housing. Many others came from the Fontana/San Bernardino area, not far from where I grew up, where for days and even weeks at a time, the mountains are obscured by smog. My escape from this unpleasant skyline was reading and camping deep in the woods. Many of our students did not have the ability, or sometimes, the interest or encouragement, to engage with escapes that provided refuge from the familiar landscape. Imagining the very concept proved difficult. Writes one student in her final essay, I came to understand in this course that there is a real importance to thinking about beauty. It seems to touch every area of my life, and now I cannot stop paying attention to it.

In thinking about how to approach teaching and studying writing, poetry in particular, Koch’s advice still seems so obvious and crazily relevant. Apprentice, journeyman, master. Imagining ourselves in the Era of Information to have evolved beyond listening to the voices of those who wrote before us is nothing short of silly. Learning to train the eye and the ear, to pay attention in a way that helps develop an aesthetic sense of the world, is perhaps one of the most important “skills” we can teach, even when the marketability of such skills seems to amount to little. If you don’t develop a sense of voice and your real size in the world, what will you have to think about besides the blouse on sale at Filene’s Basement when all of your friends are working or dead?

Heather Altfeld’s recent publications include poetry in Narrative Magazine, Poetry Northwest, Pleiades, Greensboro Review, Superstition Review, ZYZZYVA, North American Review, Green Mountain Review, and others. She teaches and lives in Chico, CA and is at work on a children’s book and a second book of poetry. Heather is featured in 299.2, Spring 2014.

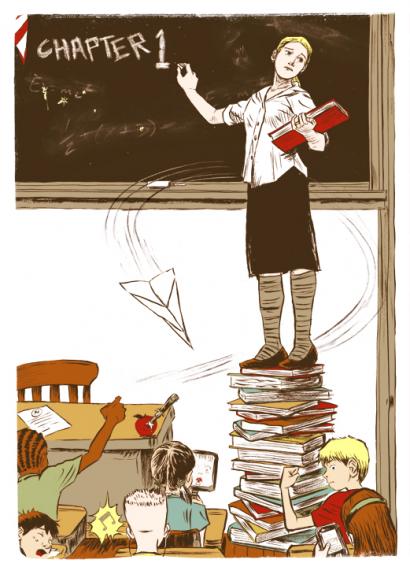

First image by: Ryan Inzana is an illustrator and comic artist whose work has appeared in numerous magazines, ad campaigns, books and various other media all over the world. His graphic novel Ichiro was the honor selection for the Asian/Pacific American award for young adult literature and was also nominated for an Eisner. You can see more of his work at www.ryaninzana.com. Most recently, Ryan has contributed an animated comic adaptation of Issac Asimov’s short story Nightfall to the July iPad edition of Popular Science magazine. It is now available on iTunes: http://lnkd.in/dcWm-kT

Second image by: Hye Jin Chung is a New York-based Korean illustrator. You can find her work in various magazines. She and other cool artists contributed illustrations to the upcoming book The Who, the What and the When, which will be published this fall. Hye Jin Chung is featured in issue 299.2.