Westing in America

The West is a noun

Getting there is a gerund

There were good reasons to leave England in 1635. Plagues often broke out during summers. Poverty was widespread. Heavy taxes were levied to pay for the wars with France and Spain. Civil war was imminent. Opportunities for a new life were there to be grasped in the American colonies. And families were stressed, especially when the mother had died, leaving the father with two young boys to be raised.

Probably some of these reasons account for the arrival at the Massachusetts Bay Colony of William Meeker, age 15, and his brother Robert, 10, aboard the ship Abigail in 1635. Both were indentured servants to a migrating family. They had left their home in Leamington, Warwickshire, on the Avon River a few miles upstream from Shakespeare’s birthplace in Stratford. Whether they were sent by their father Albert, or ran away from him, is unknown. The boys were a small part of the westward movement that peopled America.

According to Ken Keigley, a Meeker descendant and a gifted genealogist who has devoted many years to charting the Meeker history, William Meeker’s name appears next at the New Haven Colony where, as a free man, he took the oath of fidelity to the King of England in 1644. Two years later William married Sarah Preston, who had migrated from England with her family. William and Sarah finally settled in Elizabethtown, New Jersey, where William was appointed the town’s first constable. Their six children were raised there.

The family seemed content to stay put for the next century or so in New Jersey. They were farmers and fishermen, and one, Joseph Meeker, owned a small ship used for coastal trading and transport. They owned land, often adjacent to one another, in Essex and Morris Counties, where they prospered and proliferated. They were comfortable but not wealthy, respected but not important people.

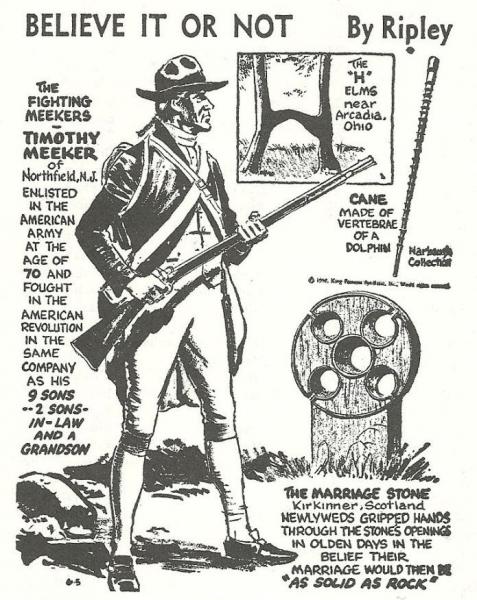

When the American Revolution began, the Meekers found plenty to do. Their location in coastal New Jersey was a good place to gather information important to the Continental Army, and several Meekers served as spies and couriers of strategic information to General Washington. Others simply joined the army, forty-nine of them according to military records. One of William Meeker’s great-grandsons, Timothy, enlisted at the age of 70, along with nine sons, two sons-in-law, and one grandson. At a time when many loyalists were fleeing to Canada rather than rebelling against the English crown, there is no evidence that Meekers were among them.

As the American frontier was pushed to the west and government inducements of free land were offered to settlers in the early 1800s, some Meekers decided to move on. They show up in Ohio, Indiana, Illinois and Iowa. Their westward movement was a little like molasses on a slight slope. The forward part moved slowly, always leaving some of its substance behind. Often it was the second or third generation that went west, with some elders and siblings holding fast to the land they farmed.

One such young man was Ezra Meeker, born on a farm near Indianapolis in 1830. At age 21, he was married to Eliza, a neighbor’s daughter, and they had a newborn son. Ezra figured it was time to own land rather than remaining on his parents’ homestead, so he and his family set off for Iowa. They spent one bitterly cold winter on a farm in western Iowa near Council Bluffs. If they had stayed there, they could have purchased land inexpensively, but there was news that settlers in Oregon Territory were receiving 320 acres of free land from the government. The miserable Iowa winters and the prospect of free land were enough to persuade Ezra to load his wagon and ox team to travel the Oregon Trail in 1852.

Recommended

Nor’easter

Post-Op Appointment With My Father

Cedar Valley Youth Poet Laureate | Fall 2024 Workshop