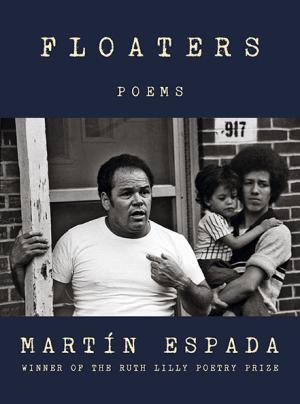

A Review of Martín Espada's Floaters

Sunburnt, bug-bit, and flat broke, the poet Hart Crane wrote a letter to his friend Waldo Frank, occasionally gazing through his little study’s back window at the mango tree on Villa Casas, his family’s winter retreat on Isla de Pinos, thirty miles off the southern coast of Cuba across the Gulf of Batabanó. He was transfixed by the vibrant green of the island’s mountains, the heavy perfume of oleanders and mimosas. Isla de Pinos was like another world. He’d vacationed with his family here once before, as a teenager eleven years ago, but had arrived this time to get away from the distractions of New York—and to work on his monumental poem The Bridge. By the summer of 1926, however, the plantation had long since fallen into disrepair with overgrown groves of grapefruit and orange trees, the old house’s roof rotten and leaky. At first energized by the decaying grandeur of the place, Crane was now depressed, despairing at having made no real progress on what he hoped would be a new modern epic, his answer to T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land. “I’m writing nothing,” he confessed to Frank. Poetry felt like “mere wordpainting and juggling,” and “the whole theme and project seems more and more absurd.” Crane was losing faith in The Bridge even as he admitted that “the very idea of a bridge...is an act of faith.”

In the coming months, he would overcome his doubt completely and enjoy the most productive period of his writing life, finishing sizable portions of The Bridge in a frenzy, along with a number of shorter individual poems, until an October hurricane ended his stay on the island. As poet and Crane biographer Paul Mariani vividly describes the scene, the storm “smashed into the Isle of Pines,” and “Villa Casas, along with so many other houses, was badly damaged and the sagging roof finally torn apart….the walls of the house began collapsing around them and the plaster ceiling buckled then came down in sections.” Crane returned to New York, and in the days following the hurricane, President Calvin Coolidge initiated Operation Rescue, ordering the US Navy to send the USS Milwaukee to Cuba to help those suffering from the devastating aftermath of the storm, the ship baking thousands of loaves of bread for the victims.

Espada promises to fight, which itself becomes a victory only made possible through poetry.

Upon its publication in 1930, The Bridge was received by critics as a flawed if ambitious failure, but over the years the famously difficult long poem would be recognized as an important artistic achievement and canonized as a classic of American modernism. To casual readers today, however, Crane is perhaps more famously remembered not for The Bridge but for his death in 1932, when he drowned in the Gulf of Mexico.

In his poem “Be There When They Swarm Me,” dedicated to the aforementioned poet and biographer Paul Mariani, Martín Espada recounts his friend and colleague “squeezing my arm to tell me about Hart Crane, / who leapt from a ship to drown at sea: Did he struggle / to regain the surface, suddenly sobered by what he’d done?” Like so many of Espada’s poems, this one springs from a deep well of gratitude for an elder mentor, who “called me brother...spoke the word poet like a benediction.” Espada empathizes with his friend’s failing body (“your spine a wreck”) and mind (“your wobbly brain”), ending with a promise to “be there,” not despite our inevitable suffering, but because of it: “We will win, though we know we cannot win.” Rather than accept the futility of human mortality and shrink in resignation from it, Espada promises to fight, which itself becomes a victory only made possible through poetry.

Crane’s suicide is not the only specter of watery death haunting the pages of Espada’s latest book of poems, Floaters. It’s The Bridge, however, that comes to mind first as a useful contrast for entering the pages of Floaters and understanding the aesthetic principles beating at its heart. In Crane’s hands, the Brooklyn Bridge sinks into the realm of what he called “intrinsic Myth,” encrusted with obscure allusions typical of the high modernist style. Weighed down by an essentializing American symbology, from Christopher Columbus to Manifest Destiny, the poem lurches toward a unified national identity. “The form of my poem,” he explained to Frank, “rises out of a past that so overwhelms the present with its worth and vision.” Like The Waste Land, however, whose “London Bridge is falling down falling down falling down,” Crane’s The Bridge never fully coheres, by design, relying instead on Eliot’s “fragments I have shored against my ruins” to suggest a modern American consciousness utterly incapable of conquering despair, much less communicating clearly the outlines of its suffering.

Crane’s suicide is not the only specter of watery death haunting the pages of Espada’s latest book of poems, Floaters. It’s The Bridge, however, that comes to mind first as a useful contrast for entering the pages of Floaters and understanding the aesthetic principles beating at its heart. In Crane’s hands, the Brooklyn Bridge sinks into the realm of what he called “intrinsic Myth,” encrusted with obscure allusions typical of the high modernist style. Weighed down by an essentializing American symbology, from Christopher Columbus to Manifest Destiny, the poem lurches toward a unified national identity. “The form of my poem,” he explained to Frank, “rises out of a past that so overwhelms the present with its worth and vision.” Like The Waste Land, however, whose “London Bridge is falling down falling down falling down,” Crane’s The Bridge never fully coheres, by design, relying instead on Eliot’s “fragments I have shored against my ruins” to suggest a modern American consciousness utterly incapable of conquering despair, much less communicating clearly the outlines of its suffering.

All of this is to say that nothing could be further from the poetics of Espada’s Floaters, whose bridges, despite their clarity, are more complicated, manifold, at once real, solid structures that are still deeply metaphorical figures. Some of the bridges in Floaters are not even built yet, but they stand more powerfully as an invitation to imagine a more just, integrated future by refusing to deny the truths of history. Instead of being hamstrung by “intrinsic Myth” or overwhelmed by the delusional past of Americanist narratives, as Crane arguably seems to have been, Espada faces its ugly truths, requiring that readers do so, too.

We linger on the first of such bridges in “Jumping Off the Mystic Tobin Bridge,” returning to Espada’s life as a lawyer in Chelsea, Massachusetts, where he defended low-income Spanish-speaking tenants from 1987 to 1993. The poem recounts an instance of everyday racism, a cab driver warning the suit-and-tie-wearing Espada, on his way from court that “There’s a lotta Josés / around here.” After the poet “leaned into his ear...and said: I’m a José….I’m Puerto Rican,” the rattled driver “shouted: What do you want me to do...jump off the bridge?” Here is the moment of truth, when the poet admits “for a flash, I wanted him to jump” but then peels back a layer of text to reveal the underlying social dynamic that animates this entire book: “The driver, the cops, the landlords, the judges / all wanted us to jump off the Mystic Tobin Bridge, all wanted us to sprout gills / like movie monsters so we could paddle underwater back to the islands.” The final stanza demands our attention as it rebuts the systemically racist, white powers-that-be, cutting to our present moment with the arrival of migrants and refugees who are destined to be “builders of bridges” themselves. “You can walk across the bridges they build,” suggests Espada. “Or you can jump.” Bridges, then, invite connection across the chasm of difference, pointing the way toward a new, distant shore; the choice remains: to traverse or to jump.

All poetry carries the possibility for incantatory magic, but on Espada’s tongue it is especially potent.

The American failure to build such bridges is never more evident than in the book’s title poem “Floaters,” the dehumanizing term certain members of the Border Patrol use for the dead bodies of migrants crossing the Rio Grande. Espada honors two of the dead, a father and young daughter, by saying their names, asking the reader to do the same: “Say Óscar Alberto Martínez Ramírez. Say Angie Valeria Martínez Ávalos. / See how they rise off the tongue.” Speaking the names of the dead becomes a creative act of historical witness: “Carve their names in headlines and gravestones,” Espada commands, and even on the page the reader can hear the poet’s fist pounding. “Enter their names in the book of names.” All poetry carries the possibility for incantatory magic, but on Espada’s tongue it is especially potent; “Floaters” ends with a further rousing imperative, reversing the power dynamic inherent in the term “floaters”: “may the men / who speak of floaters…float through the clouds to the heavens” and “plunge back to earth” on “the Mexican side of the river.”

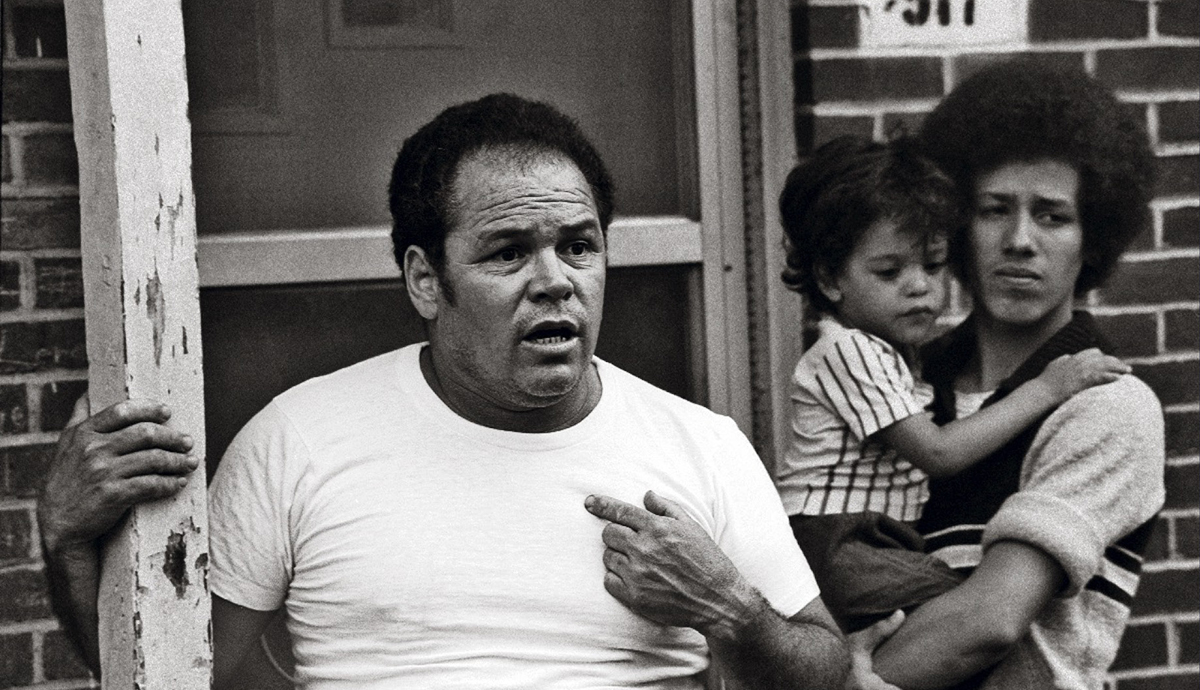

These two opening poems clearly announce the broad contours of Floaters and Espada’s concern as an activist and an artist with both literal and figurative bridges, their historical functions and malfunctions, and the promise they hold for social justice. This principle has always found expression in Espada’s extensive body of work, as he recognizes his many mentors as bridges, too, from the poet Clemente Soto Vélez, who served as a bridge between the Puerto Rican independence movement on the island and the mainland; to his father Frank Espada, whose photographs documented many communities of the Puerto Rican diaspora; to his “second father,” the poet and community organizer Jack Agüeros.

Another prominent mentor Espada honors and memorializes in Floaters is Luis Garden Acosta, the community organizer who died in 2019. In 1982 he founded a grass-roots organization in Brooklyn called El Puente (The Bridge). The poem “Morir Soñando” recounts the poet’s visit with Garden Acosta to the empty church that would become El Puente, then only a dream of a community center that would offer “ESL classes,” “clinics on contraception,” “karate lessons,” and “workshops on Puerto Rican history.” At lunch, Espada is introduced to the drink from the Dominican Republic called morir soñando, in English “to die dreaming.” On Espada’s tongue, the drink becomes an “elixir,” leading to “a vision” of a radically different future, understanding at last Garden Acosta’s hopeful prophetic dream of El Puente as a bridge for “a generation condemned to amnesia” to unforget their history, to die dreaming themselves.

If Floaters initially calls to mind Hart Crane’s The Bridge, because of its centrality in the modern American literary canon, “Morir Soñando” evokes the Mexican poet Octavio Paz’s slim gnomic poem “El Puente,” from his 1962 collection Salamandra, formally quite different from Crane’s sprawling fragmented epic but thematically offering a more apt frame for thinking about Espada’s book:

El Puente

Entre ahora y ahora

entre yo soy y tú eres

la palabra puente.

Entras en ti misma

al entrar en ella:

como un anillo

el mundo se cierra.

De una orilla a otra

siempre se tiende un cuerpo,

un arcoíris.

Yo dormiré bajo sus arcos.

The Bridge

Between now and now,

between I am and you are,

the word bridge.

Entering it

you enter yourself:

the world connects

and closes like a ring.

From one bank to another,

there is always

a body stretched:

a rainbow.

I'll sleep beneath its arches.

Just as Luis Garden Acosta’s dream eventually came true, his vision for El Puente becoming a reality that is still thriving in the world, so, too, does Espada operate throughout Floaters at the same transformative moment between word and world, palabra y mundo, on a bridge made of poetry where “the world connects.” In his 1974 essay “The Closing of the Circle,” Paz elaborates on this faith in poetry as a bridge: “Poetry is the bridge between utopian thought and reality, the moment when the idea becomes incarnate. Poetry is the true revolution that will end the discord between history and idea.” All of Espada’s work is a “true revolution” of this kind.

Espada takes the salvific function of poetry seriously, both personally and politically.

“Standing on the Bridge at Dolceacqua” offers the image of a seemingly quite different bridge, one that spans cultural difference toward the redemption to be found in unconditional love: the stone bridge near the border between Italy and France, made most famous by Monet’s 1884 painting. The poet stands on the bridge with his wife, who the entire book is dedicated to, “poet, teacher, / amati, like amada in Spanish, the word for beloved.” Espada remembers repeated instances of racist violence that he suffered as a teenager at the hands of Italian Americans in his school, but is then finally able to let those memories go, as his Italian American beloved “leads me / across the bridge.” This poem initiates a lively and poignant section of love poems, some of which have graced the pages of the North American Review, from the sonnet “Love is a Luminous Insect at the Window,” which presents the redemptive power of love as a beautiful luna moth, to “Aubade with Concussion,” which portrays his lover as a teacher saving a traumatized student by instructing her to “Take this journal. Write it down,” the journal’s cover offering the fitting poetic imperative to “Dream,” dream begetting dream toward salvation.

Espada takes the salvific function of poetry seriously, both personally and politically, as evidenced by the powerful 2019 anthology that he edited for Curbstone Books, What Saves Us: Poems of Empathy and Outrage in the Age of Trump. Despite our new presidential administration, the Age of Trump is hardly over. As Espada explains, the man’s name is merely “a symbol for the destructive forces with which he is now synonymous,” including explicit and systemic forms of white supremacist racism, as well as subtle and not-so-subtle attempts to undermine the signifying power of language, from alternative facts to self-aggrandizing exaggeration to outright propagandistic lies. Poets must, Espada implores, “take back the language, resisting the corruption of words themselves.” The connection between word and world, palabra y mundo, relies on this poetic retrieval and resistance.

Floaters culminates with a poem born from equal portions empathy and outrage in the Age of Trump, “Letter to My Father,” written in October 2017 after Hurricane Maria ravaged Puerto Rico. Espada returns the reader to Utuado, where his father was born and his great-grandfather served as mayor: “His name was Buenaventura,” his father explains to the young poet on a childhood trip to Puerto Rico. “That means good fortune.” Readers familiar with his work will recall the title essay of Espada’s 2010 collection The Lover of a Subversive is Also a Subversive, which describes searching unsuccessfully for his great-grandfather’s grave in Utuado; as well as the poem “La Tumba de Buenaventura Roig” from his 1990 collection Rebellion is the Circle of a Lover’s Hands, where the poet learns that in Utuado his great-grandfather “built the stone bridge / crushed years later by a river.” In “Letter to My Father,” Espada describes another “bridge collapsed,” the “rolling wall of mud,” the death and destruction caused by the storm, and the botched response by the United States government to the increasingly lethal humanitarian crisis, exemplified by the now famous image of Donald Trump, who “flips rolls of paper towels to a crowd / at a church in Guaynabo, Zeus lobbing thunderbolts on the locked ward / of his delusions.” To combat this jealous god, Espada invokes his own father as an intervening God dispensing justice at last:

Stride from the crowd to seize the president’s arm before another roll

of paper towels sails away. Thunder Spanish obsenities in his face.

Banish him to a roofless rainstorm in Utuado, so he unravels, one soaked

sheet after another, till there is nothing left but his cardboard heart.

This climax of Espada’s outrage in the Age of Trump is tempered by his empathy for those suffering and trying to survive in “Campamento los Olvidados: Camp of the Forgotten.” The poet’s resolve to return to Utuado to scatter his father’s ashes is a promise not to forget, one that the reader is also compelled to heed. Floaters is itself a promise that poetry does indeed have the power to save us, a promise between the word and the world, a promise only made possible by “the true revolution” of poetry, which is the ultimate promise of El Puente: to build a bridge between us.

Recommended

A Review of When We Were Gun: A Narrative Poetry Cycle by Deborah Schupack

A Review of Apostasies by Holli Carrell