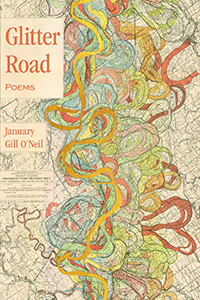

A Review of Glitter Road by January Gill O’Neil

A finalist for the 2024 New England Book Award and now in its third printing, Glitter Road by January Gill O’Neil is a gut check in its relentless pursuit of truth-telling. Throughout this collection, O’Neil constructs a cartographic narrative concerned with violences against the black body, racist ideologies and personal loss. As she navigates through these physical and emotional terrains, what glitters is a woman trying to reconcile herself to a ruptured past while trying to steady herself on the road ahead. When she finds love again, she pens lines with such sensual tenderness—a pleasure that feels like prayer.

In 2019, O’Neil and her family travelled south when she received the John and Renee Grisham Fellowship at the University of Mississippi. It was there that O’Neil encountered an unapologetic allegiance to the Confederacy, evident in the unabashed use of the term “rebel” to name everything from businesses to consumer products. In the poem, “Rebel Rebel,” she writes: “Every inch of this place has been touched by trauma. I feel it in the hills. / In the loam. In the wilt of wild daffodils. Who honors the enslaved rebels?” In this poem the text suggests that in some ways Mississippi willingly clings to its turbulent past, despite it being a dreadful, unspeakable memory for others. The constant repetition of the word rebel builds an urgency and intensifies the speaker’s repulsion.

It’s difficult to travel to Mississippi without being exposed to any aspect of Emmett Till’s story. This act of racial terror is remembered by highway signs, a memorial, a ten-stop self-tour and so on. It’s no surprise that Till appears in several poems; in some, he is briefly referenced, while in others, he is the central focus. In the poem, “Three white Ole Miss students use guns to vandalize a memorial to lynching victim Emmett Till” O’Neil writes:

They pose their bodies as if they’ve just bagged

their first 10-point buck. One holds a shotgun,

another squats below the shot-up sign

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

This is an old story, a Southern Gothic,

To deny this boy’s life and then

deny the marker that says he lived

breaks me every time.

Perhaps the intent is to immerse the reader in the prolonged grief often felt by those who have been targets or witnesses of ongoing racialized violence. The student’s deed is compared to a hunting trip—an image that evokes memories of animal trophies for some, while for others, it elicits Emmett Till being pursued by a vengeful mob. Here the speaker forces us to face the perpetrators’ irrefutable irreverence for Till’s memory.

This collection contains other poems that make temporal leaps to expand upon O’Neil’s concerns about racialized violence and divisive ideologies. The poem “Driving Through Mississippi After the Capitol Hill Riot,” offers a stern reminder to the nation of its history: “America, haven’t we been here before? Standing our ground / in failing light, our breaths held, not knowing what will happen next.” These lines evoke an American newsreel, bringing to mind a nation repeatedly at the crossroads. The phrases “failing light,” “breaths held,” “not knowing” serve as an exhortation. In “After Daunte Wright’s Murder, I Teach a Poetry Class to High Schoolers on Zoom,” the speaker questions: “Can art effect change when / every bullet blooms the color of elegy?” Both of these poems convey a sense of exhaustion and rejection of current conditions in America almost seventy years after Till’s brutal killing. It seems as if O’Neil’s proximity to death has heightened the stakes.

We see a self-assured, uninhibited speaker—still grappling with grief but determined to actively pursue joy and stand in her truth.

Although Glitter Road is a collection laden with personal and collective grief, there is a sense of hope and perseverance flourishing in many of the poems. “Narcissi in January” is a poem that describes harsh winter weather conditions while imbuing the lines with self-reflection, perhaps even some regret:

The syntax of strange,

lonely hours. How deep, how often have I

been touched? The knowledge of not enough

crunches like ice in my mouth . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Two-faced, the coldest month of the year.

January, the first narcissi are breaking

the surface.

The narcissus is a harbinger of spring, a perennial among the first flowers to emerge after the winter frost thaws. Here, the speaker reassures that absence, death, rest, and renewal are natural phases of decline and growth. O’Neil reveals personal resilience in lines from “Begin Again,” a poem about a new love interest: “perhaps the world begins here / begins again / which is no small thing.”

In sections three and four there is a change: we see a self-assured, uninhibited speaker—still grappling with grief but determined to actively pursue joy and stand in her truth. In the poem “Woman Swallowed by a Python in Her Cornfield,” the speaker declares: “I am done telling the kinder story. I am a myth of my own making.” In “The Great Hello,” there is a pervasive sensuality made clear:

I am an over-easy egg

trying not to break her yolk,

but I do. The joy of leaving the body,

tender and shimmering.

In “Mississippi Season,” the speaker initially describes herself as “a kind of carnival fish,” only to reveal that she is undergoing a transformation shaped by the gaze of her new lover:

Dumb luck that someone

flips a red ring on the mouth

of a glass jar and just like that,

I am kissing again,

kissing a man so luminous—

so beautifully flawed—

I can barely look at him.

This poem holds space for women at or nearing fifty, who feel erased by society. O’Neil herself expresses doubt about finding affirmation and love again after reaching her “half-life.” Some of the poems in the third and fourth sections are especially honest—sometimes giddy, but laced with grown woman sensibilities. The daring poem “Clit Ode” pays homage not only to her sensuality but also to other Black women writers, such as Toi Derricotte and Nikky Finney, who also wrote poems about the clitoris.

In the titular poem, “Glitter Road,” we see O’Neil’s map well-traveled. The collection opens with a poem about her ex-husband’s death and concludes with one that discovers hope in a momentary, infinitesimal observation. Her journey has been as much about self-discovery as it has been about place—a quest to rediscover faith in both the mundane and the miraculous. In that moment while driving down the road in her car, she seemed to be worlds apart from grief:

Hard not to feel good riding a glistening wave,

my tires now bespeckled with a purple sheen

that’s tough to rid or wash away, the road ahead

made beautiful by this temporary shine.

Recommended

A Review of When We Were Gun: A Narrative Poetry Cycle by Deborah Schupack

A Review of Apostasies by Holli Carrell