A Review of "Bone Chalk" by Jim Reese

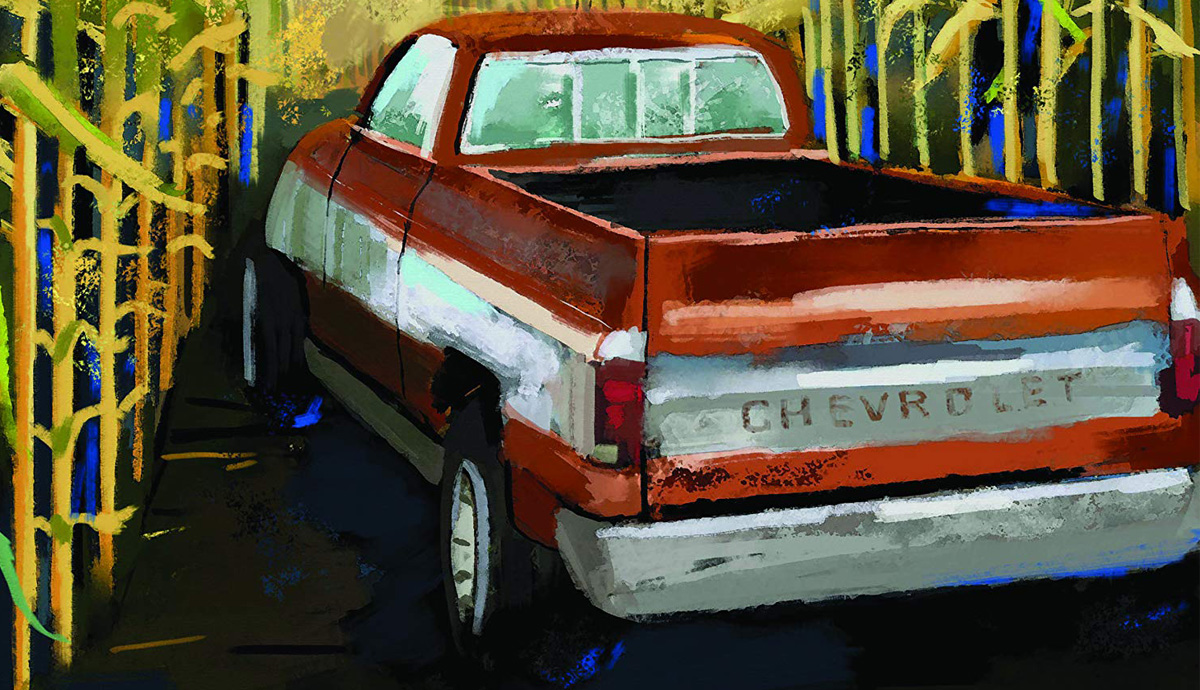

Jim Reese’s new memoir Bone Chalk well illustrates some important lessons acquired in the writing and publishing of his previous collections of poetry. One of the more important of those is the necessary use of significant detail in an attempt to share an experience rather than simply tell about it. And Reese’s desire to share his experiences is evident from the opening chapter of the book, “How to Become a Regular,” where the reader is invited directly into the scene as an observer, along with the author, of an evening in a small town bar: “Picture Main Street. Pickups in a row like a used car lot, Chevy vs. rusted Ford….” The invitation continues as the author steps inside “Tootie’s Chicken, full of farmers”: “See Pauline and Linus Cummins, two out-of-towners…. Now, imagine a more serious affair than prices dropping $2.00 a bushel.”

In this collection of essays, Reese shares a variety of experiences: of his youth in Omaha; as an undergraduate student in a state college in Nebraska; of living, working and raising a family in small town and rural Nebraska; and of his job teaching writing at a South Dakota college, two South Dakota prisons, and at San Quentin. Embedded in these experiences are insightful comments on the political and economic concerns that daily affect rural and small town folks, and that have adversely affected many of those presently confined in America’s prisons. An experience in chapter two: “I’m in the machine shed handing Carl tools as he rebuilds a 350 motor,” soon invokes such comments as, “Here, with everything spread out—where you can actually see the sky, piles of wealth and extravagance stand in sharp contrast to some families struggling to get by”; “That romanticism of the small American family farm diminished in the late seventies and early eighties with the proliferation of corporate farming and American greed.” And, fully aware of himself as an outsider to such things: “I’ve never sat at the kitchen table calculating unforgiving ground—whole sections drying up at a time—families splitting up out of stubbornness and greed.”

In this collection of essays, Reese shares a variety of experiences: of his youth in Omaha; as an undergraduate student in a state college in Nebraska; of living, working and raising a family in small town and rural Nebraska; and of his job teaching writing at a South Dakota college, two South Dakota prisons, and at San Quentin. Embedded in these experiences are insightful comments on the political and economic concerns that daily affect rural and small town folks, and that have adversely affected many of those presently confined in America’s prisons. An experience in chapter two: “I’m in the machine shed handing Carl tools as he rebuilds a 350 motor,” soon invokes such comments as, “Here, with everything spread out—where you can actually see the sky, piles of wealth and extravagance stand in sharp contrast to some families struggling to get by”; “That romanticism of the small American family farm diminished in the late seventies and early eighties with the proliferation of corporate farming and American greed.” And, fully aware of himself as an outsider to such things: “I’ve never sat at the kitchen table calculating unforgiving ground—whole sections drying up at a time—families splitting up out of stubbornness and greed.”

The longest essay in the book, “Never Talk to Strangers—12 Years in Prisons and What Criminals Teach Me,” is a compilation of short pieces that center on a single question, “Why?” Included here are the John Joubert killings in Nebraska, as well as the murder of a good friend of Reese’s while she was babysitting. Juxtaposed to such memories are Reese’s present-day interactions with inmates in his job teaching writing in prisons. The central question is ever present. Why do criminals do what they do? Why do we incarcerate more of our people here in the United States than anywhere else in the world? Why are some people in prison for selling marijuana, while others go on selling opioids and profiting from the often tragic consequences?

In “Coda,” the final piece in “Never Talk to Strangers,” Reese writes, “Things that have altered me are crimes. When I was young, I felt like an outsider, a stranger (especially as an only child), someone who was never afraid to ask, ‘Why?’ I’ve never shaken that. Nor do I intend to. We as humans are indecisive—are unpredictable. We act out.” (Indeed. But why do we most often act out against the innocent, rather than against those sponsors of the corporate greed that are so obviously oppressing us all?)

Yet Bone Chalk is not all seriousness, and Reese is also quite adept at sharing the more humorous aspects of his life. Among the lighter works offered here are a series of experiences involving Reese’s relationship with his wife’s family, titled “The Mother-in-Law Archives.” Included as well are several compilations of humorous quips found, as the title of each makes clear, on “Midwest Bumper Stickers.” And in “My Life as Willy the Wildcat,” Reese shares the ups and downs of his experiences trying out for and becoming the school mascot at the state college he attended as an undergraduate, offering the reader a wildcat ride, to say the least: “As the mascot, I was invited to the parties after the game. Every Saturday night was trick or treat for Willy—I was on the prowl.”

In this debut memoir, Jim Reese shares a wide variety of personal experiences that few readers would be able to relate to in any other way. As he writes in “The Mother-in-Law Archives,” “If you need something—a blow torch, nunchucks, twist-ties, marbles, propane, a chandelier, suspenders, a curtain rod, spare tire, a putter, basin wrench, bell bottoms, a bowling ball—anything; she’s your woman.”

And if throwing the door open to new experience is one of the reasons you choose to read, Bone Chalk is definitely your book.

Neil Harrison’s stories have appeared in various journals, most recently in Pinyon Review. His poetry collections include In a River of Wind, Into the River Canyon at Dusk, Back in the Animal Kingdom, and Where the Waters Take You. He formerly taught English and Creative Writing and coordinated the Visiting Writers Series at Northeast Community College in Norfolk, Nebraska, where he now lives with his third drahthaar, the Happy dog.

Recommended

A Review of Portable City by Karen Kovacik

A Review of Haircuts for the Dead by William Walsh

A Review of Birdbrains: A Lyrical Guide to the Washington State Birds