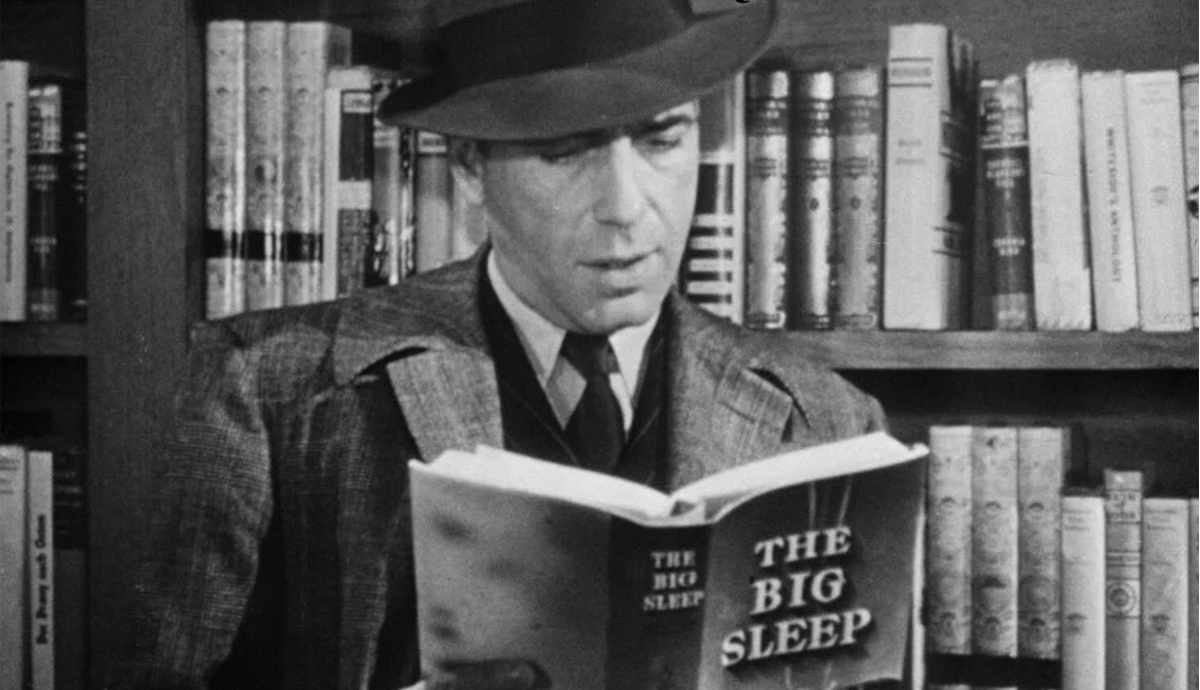

I Was a Part of the Nastiness Now: A Review of "The Big Sleep by Raymond Chandler

In “Against Epiphanies,” Charles Baxter makes a passing reference to narratives of eloquence (action-based) versus narratives of sensibility (the pursuit of insight and recognition). Genre stories are more action-oriented, but when Raymond Chandler shifted from writing crimes stories for the pulps to writing his first novel, the literary-inflected The Big Sleep, he pushed the boundaries of detective fiction into a hybrid form with a greater emphasis on psychological interiors, mood, and irony.

To help accomplish this shift, Chandler uses setting and props to define the inner lives of his characters. General Sternwood, in his crowded hothouse, is in exile, waiting to die, asserting no authority, surrounded by orchids and plants that have “the newly washed fingers of dead men.” Vivian, one of his two daughters, moves about in a bedroom whose ceiling is “too high,” the doors “too tall,” and the “enormous ivory drapes [lying] tumbled on the white carpet a yard from the windows.” These details reflect her lack of order, control. Younger sister Carmen too is associated with excess, “dirty” oil stains that dot the backyard.

Irony and voice further push The Big Sleep into a landscape of insight.

Marlowe’s integrity is defined by the spaces he inhabits. His office doesn’t put on “much of a front” and his apartment is his personal, spartan sanctuary. When Carmen crawls, unannounced, under the covers, naked and giggling, Marlowe interiorizes:

I didn’t mind what she called me, what anybody called me. But this was the room I had to live in. It was all I had in the way of home. In it was everything that was mine, anything that took the place of a family. Not much: a few books, pictures, radio, chessmen, old letters, stuff like that. Nothing. Such as they were they had all my memories.

His is a lonely life, and chess, a game with knights, represents Marlowe as a questing hero. Looking at the chessboard, Marlowe tells us, “Knights had no meaning in this game. It wasn’t a game for knights.” But down these mean streets he must go, a tarnished knight full of world-weary idealism. He rejects Carmen’s advances, sends her from his apartment, and admits to his own humanity, how he was tempted by her: “I . . . tore the bed to pieces savagely.”

Irony and voice further push The Big Sleep into a landscape of insight. There is a lot of gunplay, sudden violence in Chandler’s pulp stories, but in the six novels that follow Marlowe’s debut, he never kills anyone. Instead, action is downplayed in favor of attitude. In “Killer in the Rain” (one of two pulp stories Chandler “cannibalized” into The Big Sleep), the detective, in dialogue, tells Slade to put down his gun, “You don’t know enough to pop off yet. Not being bullet-proof is an idea I’ve had to get used to.” In The Big Sleep, the same line becomes inner monologue as Marlowe is confronted by the gun-toting Eddie Mars.

Through irony and interiority, Chandler more fully explores the world of the pyrrhic.

It’s a slight shift, but it hints at Chandler’s larger project of investing in character self-awareness (irony as self-protection), and Marlowe’s ability to poke fun at himself and his occasional role-playing. In a showdown with Lash Canino, Marlowe pretends to be mortally wounded:

A darkened window slid open inch by inch, only some shifting of light on the glass showing it moved. Flame spouted from it abruptly, the blended roar of three swift shots. Glass starred the coupe. I yelled with agony. The yell went off into a wailing groan. The groan became a wet gurgle choked with blood. I let the gurgle die sickeningly, one choked gasp. It was nice work. I like it. Canino liked it very much. I heard him laugh. It was a large booming laugh, not at all like the purr of his speaking voice.

What a wonderful passage. At the beginning, the language is vivid, poetic (“shifting of light on the glass”; “flame spouted”; “glass starred”). The action grabs hold and the rhythm propels us on as Chandler repeats key words from one sentence to the next (“yelled/yell”; “groan/groan” and “gurgle/gurgle”), and then he lets us fully inside, still using rhythmic repetitions (“like it/liked it”); “laugh/laugh”) as Marlowe ironically appraises his own performance (“It was nice work”). The passage ends on a Chandler signature, the simile, and contains subtle menace: Marlowe’s setting Canino up for the knockoff.

Through irony and interiority, Chandler more fully explores the world of the pyrrhic. Carmady, the hero of “The Curtain,” another pulp story that Chandler cannibalized for The Big Sleep, encounters Mrs. O’Mara and tells her that her fifteen-year-old son is guilty of murder. Get help for him, he says, suggesting he won’t turn him over to the police if she sends him to an asylum. Respectfully, she apologizes to Carmady for trying to buy him off, saying that was “nasty,” and that she was never in love with her late husband, “That’s nasty too,” she confesses. In The Big Sleep the boy is substituted for Carmen, Marlowe makes the same pitch Carmady did about an asylum, but the “nasty” aspect of the dialogue becomes an inner monologue, a moment of self-recognition, and one of the most elegiac insights in the novel:

What did it matter where you lay once you were dead? In a dirty sump or in a marble tower on top of a high hill? You were dead, you were sleeping the big sleep, you were not bothered by things like that. Oil and water were the same as wind and air to you. You just slept the big sleep, not caring about the nastiness of how you died or where you fell. Me, I was a part of the nastiness now. Far more a part of it than Rusty Regan was. But the old man didn’t have to be. . . .

Because Marlowe carries the weight of secrets, Carmen’s killing of Rusty, he too dies a little on his quest, becoming a part of the nastiness, but what does it all matter anyway, we’re all going to die. His final meditation has an aura of meaningless absurdity to it.

Perhaps the final rhetorical turn of The Big Sleep is even too much for Chandler. Instead of ending the novel at this epiphanic peak, he opts for a quick, three sentence epilogue, as Marlowe stops downtown for a couple of Scotches. “They didn’t do me any good,” he says.

Recommended

A Behind the Scenes Look at Art Selection and Cover Design for the NAR

“Doubling and the Intelligent Mistake in Georges Simenon’s Maigret’s Madwoman”

What the Birds Showed My Wounded Child, My Adaptive Adolescent, & My Wise Adult