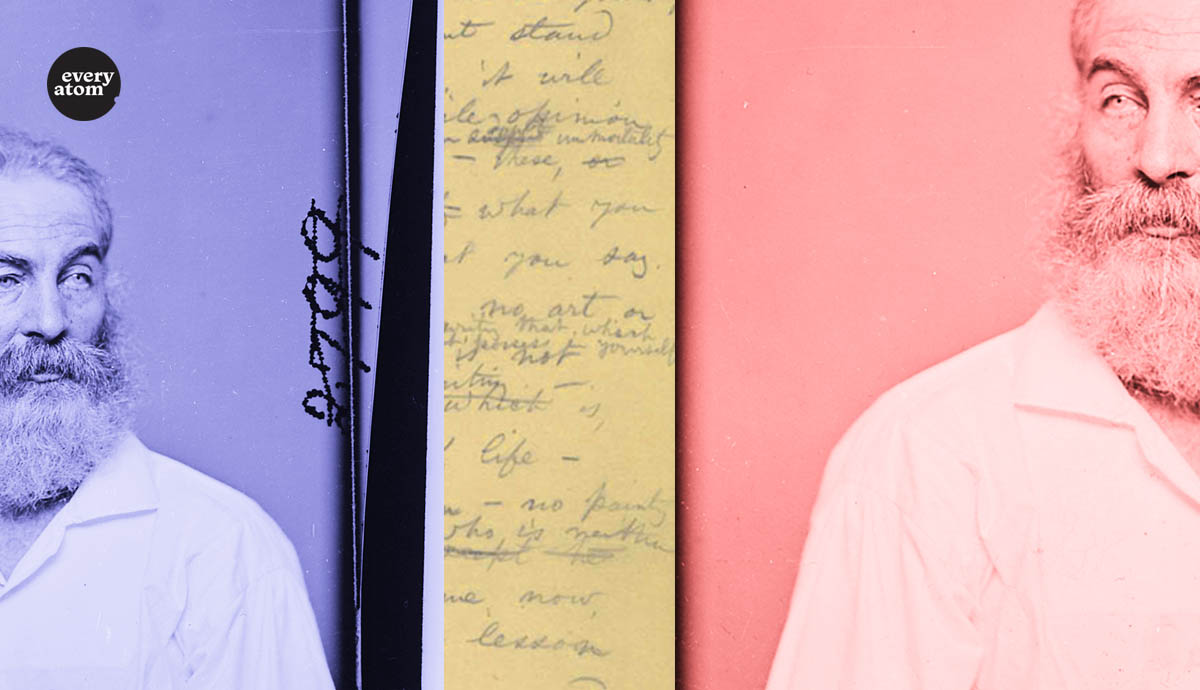

Every Atom | No. 11

Introduction to Every Atom by project curator Brian Clements

Listener up there! Here you….what have you to confide to me?

Look in my face while I snuff the sidle of evening,

Talk honestly, for no one else hears you, and I stay only a minute longer.

Very well then….I contradict myself;

I am large….I contain multitudes.

I concentrate toward them that are nigh….I wait on the door-slab.

Who has done his day's work and will soonest be through with his supper?

Let us now praise Whitman’s pronouns.

Walt Whitman’s “I” is himself— a man, mortal and time-bound, soon to depart. It is also famously, declaratively multiple. (“I am large... I contain multitudes.”) The aside has been echoed, amplified, proven throughout his poem’s pages, as in this earlier passage:

Through me many long dumb voices,

Voices of the interminable generations of slaves,

Voices of prostitutes and deformed persons,

Voices of the diseased and despairing, and of thieves and dwarves,

Voices of cycles of preparation and accretion,

And of the threads that connect the stars--and of wombs, and of the father stuff,

And of the rights of them the others are down upon,

Of the trivial and flat and foolish and despised,

Of fog in the air and beetles rolling balls of dung.

Human, weather, and insect; ecstatic and beaten; ground-near and star-flung— this “I” through which others who have been long-wordless speak, its multiple allegiances, transparence, and breadth travelling outward in every direction, is the poet’s foundational genius. The opposite of ego, of fixed identity’s narrowing, Whitman’s “I” holds the liberating awareness shared by all mystics. His “I,” both American and a kosmos, is the “I” of the 13th-century Zen master Eihei Dogen, which studies the self, forgets the self, and awakens into the ten thousand beings and things.

Whitman’s “you,” though, is different. Let us grant that the still-unknown poet assigned to himself the attention and ears of not only his living countrymen but also future, unborn readers. (And look: here we are.) To that degree, Whitman addresses his “you” to many. But throng, plurality, collective, are not how his second person pronoun most usually lives. Whitman’s second person is indubitably, profoundly, singular. The paradox empowers both voices. From English’s unambiguously singular “I,” Whitman conjures a prismatic multitude; from its numerically ambiguous “you,” he crafts a single, focused light-beam, pointed at the one person this moment receiving his words. Even as his poem works to remake a country’s self-understanding and social contract, Whitman’s continual, murmured “you” turns it into a conversation private, intimate, individual. We listen most acutely to what we feel is whispered to us alone.

Listener up there! Here you….what have you to confide to me?

This “you” looking down at the page – or perhaps it may also be down toward the imagined grave from which Whitman confides, and waits for confidence in turn to be given? –is you yourself, each time you pick up his book. Your own person and body, whose pulses race or slow with his words.

Which leads to the contract forged between Whitman and his reader, so deeply a part of his work. For this “you” is also a “you” of whom something is being asked.

Whitman’s query is urgent, demanding. It presses into your consciousness and your conscience. A request more generally made would be necessarily more muffled, blurred—someone else, after all, might be called on to answer. A request more generally made would snub the size of what the poet means us to be: one largeness speaking with and into another. By his intimate, pressing “you,” Whitman asks us to know ourselves his camarado and equal.

And to that “you,” now commensurate in size to his own largeness, the poet assigns a responsibility equal in size to his own. He tasks us to do as he has, to find out for ourselves who we are and what it means to know ourselves inseparable from everything that shares with us this singing, speaking, barking, murmuring world. Another passage holds the transfer explicitly:

You shall no longer take things at second or third hand....nor look through the eyes of the dead....nor feed on the spectres in books,

You shall not look through my eyes either, nor take things from me,

You shall listen to all sides and filter them from yourself.

Whitman’s empathy and first-hand knowing; his confidence that this one, lived life is sufficient passageway into the life of all--the poet passes them now to us, to carry directly in our own going-forward:

Will you speak before I am gone? Will you prove already too late?

In our own time of seemingly insoluble divisions and separation, Whitman’s “I” of permeable, unlimited embrace, his “you” invited into unbreakable connection, remain indispensable remindings. These pronoun-enacted understandings are curative, tender, healing, a book-long binding of what in our lives,country, and ecological home has been broken. The task is urgent. May we have not proved ourselves already too late to take it up and pass it in turn to others.

Recommended

Nor’easter

Post-Op Appointment With My Father

Cedar Valley Youth Poet Laureate | Fall 2024 Workshop