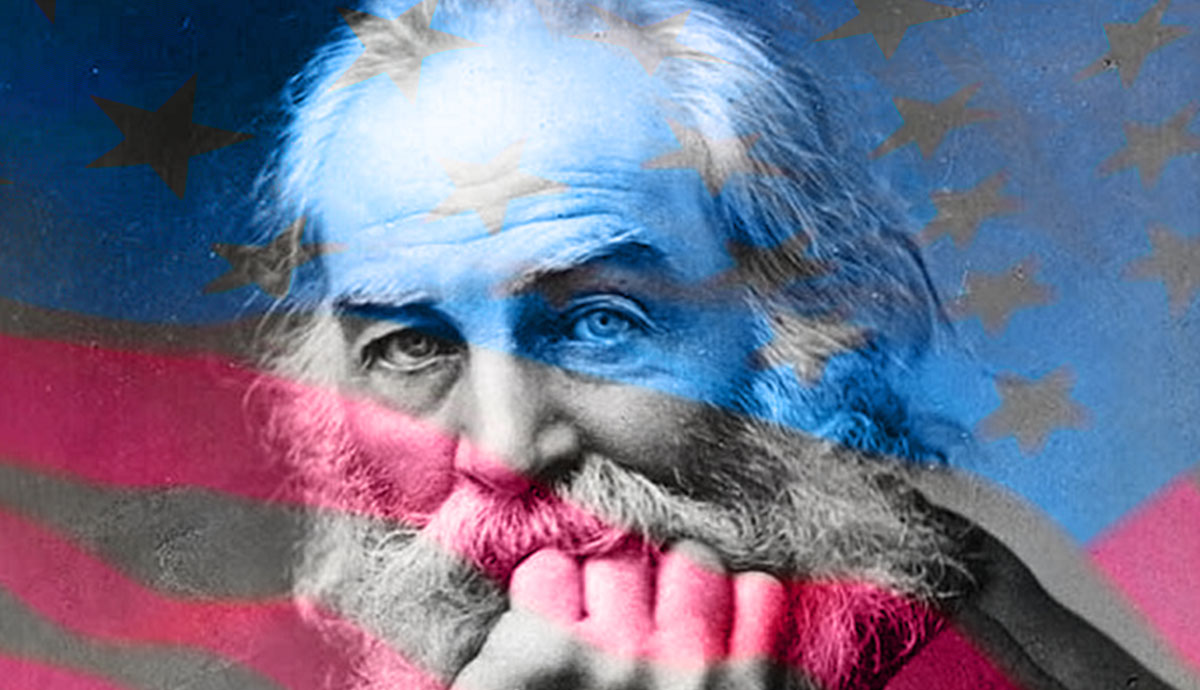

Every Atom | No. 157

Introduction to Every Atom by project curator Brian Clements

In order to read Whitman, to make my pact with him, I have to get over something that drives me crazy: the bombast, the flimflam pitch of Melville’s confidence man—the very opposite of Dickinson’s “I’m nobody,” as when Whitman writes, in the preface to the 1855 edition of Leaves of Grass:

The greatest poet hardly knows pettiness or triviality. If he breathes into any thing that was before thought small it dilates with the grandeur and life of the universe. He is a seer . . . he is individual . . . he is complete in himself . . . the others are as good as he, only he sees it and they do not. He is not one of the chorus . . . he does not stop for any regulation . . . he is the president of regulation.

Can someone who proclaims they are the “greatest” really be great? Possibly, but in that case the greatest poets are filled with pettiness, rivalry, and triviality; that is what keeps them close to the ground and away from the Profound Heights of Greatness (PHG) which, in nineteenth century American terms, is marked by Moral Purpose (MP) and High Class Didactics (HCD), signifying the Great Poet (GP) is our social and moral better, even if that entails that the GP’s work is lacking those short and intense the stabs of sensation that Poe called supernal.

The Americans of all nations at any time upon the earth have probably the fullest poetical nature. The United States themselves are essentially the greatest poem.

“Of all nations at any time”? This is American exceptionalism on a combination of steroids and acid. But something odd too: it’s so hyperbolic as to transcend its noxious content. Say, who is an American? Are these altered “states”?

Other states indicate themselves in their deputies . . . but the genius of the United States is not best or most in its executives or legislatures, nor in its ambassadors or authors or colleges or churches or parlors, nor even in its newspapers or inventors . . . but always most in the common people.

OMG. Not the ruling classes but we, the people, in order to form …

The American poets are to enclose old and new for America is the race of races. Of them a bard is to be commensurate with a people.

So then does America mean the multicultural overlay of contradicting people, black and white, immigrant and landed, Jew and gentile, Asian and Europenan, indigenous and settler? The American state has defined itself by acts of exclusion, in the law and in practice. Are we “a people?” Not yet!: “Are to” projects into a process.

We have not yet arrived. And never will. But we can move in the imperfect (more perfect) direction of the new.

Of all nations the United States with veins full of poetical stuff most need poets and will doubtless have the greatest and use them the greatest. Their Presidents shall not be their common referee so much as their poets shall.

You wish! Perhaps you could say, Poe almost does, that the United States is the country with least regard for its poets, as much now as in the nineteenth century, because disdain for poetry as anything but a moral prop is built into the fabric of these states. Whitman is echoing Shelley’s “unacknowledged legislators,” but close to George Oppen’s “legislators of the unacknowledged world.” But I also think of Rosmarie Waldrop’s refusal of poets as any kind of legislators.

The known universe has one complete lover and that is the greatest poet. He consumes an eternal passion and is indifferent which chance happens and which possible contingency of fortune or misfortune and persuades daily and hourly his delicious pay. What balks or breaks others is fuel for his burning progress to contact and amorous joy. Other proportions of the reception of pleasure dwindle to nothing to his proportions.

This comes close to Poe’s supernal pleasure principal, but for Poe it is the poem for poetry’s sake, whereas Whitman cathects his cosmogonic aestheticism onto the “greatest poet,” an imaginary object that is looking increasingly like Dickinson’s “nobody.”

The messages of great poets to each man and woman are, Come to us on equal terms, Only then can you understand us, We are no better than you, What we enclose you enclose, What we enjoy you may enjoy. Did you suppose there could be only one Supreme? We affirm there can be unnumbered Supremes, and that one does not countervail another any more than one eyesight countervails another . . . and that men can be good or grand only of the consciousness of their supremacy within them.

Not from many one but from one many. Whitman’s delicious inversions explode meritocracy and the pernicious ideology of greatness as a zero sum game.

Nobody’s the greatest. The one that doesn’t count.

“You don't understand! I could've been a contender. I could've had class. I could have been somebody. Instead of a bum, let's face it, which is what I am. It was you, Charley.”

Say, Are you nobody too? (“How dreary to be somebody.”)

This is nobody exceptionalism.

There will soon be no more priests. Their work is done.

Amen.

Brooklyn, September 25, 2019

Recommended

Nor’easter

Post-Op Appointment With My Father

Cedar Valley Youth Poet Laureate | Fall 2024 Workshop