Every Atom | No. 76

Introduction to Every Atom by project curator Brian Clements

The lines occur about two thirds of the way into the long, untitled work that later came to be known as “Song of Myself.” It’s the culmination of lines describing a maritime scene that few readers today probably recognize:

How the skipper saw the crowded and rudderless wreck of the steamship, and death chasing it up and down the storm,

How he knuckled tight and gave not back one inch, and was faithful of days and faithful of nights,

And chalked in large letters on a board, Be of good cheer, We will not desert you

This shipwreck passage is also one of those “action scenes” in Whitman’s work that present moments of heroism or of historical interest, like his passage describing The Battle of the Alamo, or the vivid section in which firefighters risk their lives in an inferno. In that section, Whitman proclaims “I am the mashed fireman with breastbone broken . . . . tumbling walls buried me in their debris,” and in this one he makes a similar identification but with greater power and concision: “I am the man . . . . I suffered . . . . I was there.”

Reading these lines in 1855, the scene would likely have been more familiar. About a year and a half earlier on December 22nd, 1853, a powerful new steamship christened The San Francisco embarked from New York on its maiden voyage. Two days out at sea, it encountered one of the most fearsome hurricanes in maritime history. The engine was wrecked, and scores of crew and passengers were washed overboard.

It’s a long and gruesome story, but one with a somewhat happy ending in that some passengers were eventually rescued thanks to the heroism of the ship’s captain. Whitman, along with most of the rest of Brooklyn and New York, followed the reporting of this sensational story.

So it was a bold move for Whitman to present himself as the heroic captain. For this reader at least, it works in the finished product, due to the strength of Whitman’s language and his inclusive insistence on the power of compassion to allow us to “dilate” and include others within ourselves.

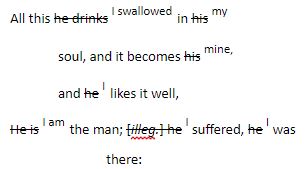

Whitman, however, was not always so sure. An early notebook dated to 1854 reveals a writer still struggling:

This is one of many notebooks and manuscript drafts that provides a glimpse of the painstaking and complex process Whitman went through composing his poems. While it can be exciting to imagine that great poems like “Song of Myself” emerged whole and complete through some process of transcendent inspiration, anyone who has spent much time writing poems knows this is usually not how it works.

What may come as a surprise to some of Whitman’s readers is the understanding that Whitman’s poetic sense of self was also something revised into being. This is just one of many passages in Whitman’s early notebooks where we discover the poet transforming a story about someone else into a story about himself, simply with a revision of pronouns. The “he” becomes an “I,” and that’s that.

I was fortunate to be one of the last people to actually hold in my hands the notebook in which this passage was drafted. It is one of many highly revised and edited notebooks in the Harned Collection at the Library of Congress. While many of the most precious of these notebooks are now sealed away from the public due to their fragility, readers can explore high quality digital images of them at the amazing Walt Whitman Archive. Many years ago, I became deeply immersed in these notebooks as part of a book project. I was startled to find that so many of Whitman’s most famous lines of poetry were originally drafted as prose, and that some of his most bold and assertive moments were originally written from a much more detached, third-person point of view.

This is a subject I have turned over in my mind for many years. What is the significance of these revisions and of Whitman’s creative process—a process that more closely resembles self-collage than it does immaculate conception? I don’t believe this complex process of revision detracts from the authority or authenticity of Whitman as a visionary poet. Whitman seems to have experienced forms and intensities of love and compassion that few of us encounter during our lifetimes, but when he sat down to make poems of these experiences, he became a poet and was subject to the same struggles with writing experienced by the rest of us.

Recommended

Nor’easter

Post-Op Appointment With My Father

Cedar Valley Youth Poet Laureate | Fall 2024 Workshop