Every Atom | No. 77

Introduction to Every Atom by project curator Brian Clements

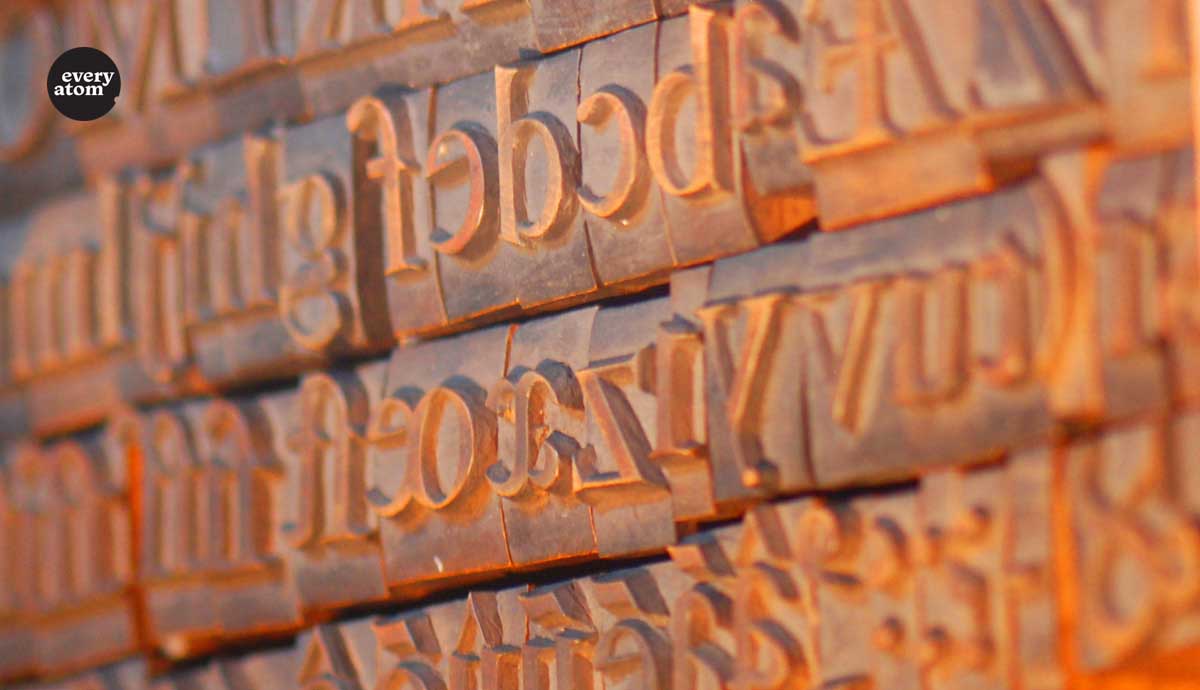

Given Whitman’s stature as one of America’s greatest poets, it’s easy to overlook that for much of his literary career Whitman simultaneously worked as a journalist. But the influence on “Song of Myself” is clear in Whitman’s push toward realism and in the narrative rhythm of free verse. Whitman spent more than a decade as a journalist in the years leading up to Leaves of Grass as an editor of The New York Aurora and The Brooklyn Daily Eagle and then filing dispatches from his travels around New York and Long Island.

Throughout the poem, we see Whitman as a witness and as a documentarian. We follow along as his “lead flies swiftly” over the page, carousing with clamdiggers “round the chowder kettle,” attending slave auctions, sharing intimate scenes as he lifts the gauze to watch a baby in its cradle and “silently brush away flies with [his] hand.” Describing a suicide, he takes us into the bloody bedroom: “I witnessed the corpse … there the pistol had fallen.” It’s unclear if Whitman actually witnessed this scene as a reporter, but we know from his “Letters from a Travelling Bachelor,” published around the time he began composing “Song of Myself,” that Whitman spent a lot of time among the fishermen of Montauk. In one letter, he even describes a wild chowder dinner and writes “I shall remember that dinner to my dying day.” Journalism provides access to myriad intimate moments. Reporters often arrive before the coroners. They’re in the room, the hospital, the refugee camp. They observe people at their most vulnerable moments or as they disclose something incredibly tender or even unforgivable.

Later, Whitman expresses his role as a medium and messenger: “through me forbidden voices.” One of the powers of journalism is giving audience to voices that are often ignored. Likewise, Whitman indulges in forcing readers to pay attention to parts of society they’d rather avoid. The opium eater, the prostitute with her “blackguard oaths,” come just before the President and his cabinet secretaries. Similarly, the great equalizer of the press places stories about the White House aside stories of opioid users.

In perhaps the poem’s most journalistic moment, Whitman renders the massacre at Goliad in stark detail. Weeks after the Battle of the Alamo, a group of Texian soldiers were captured and taken to a fort as prisoners, but General Santa Anna ordered them slaughtered. Whitman doesn’t romanticize it. He tells us of the “jetblack sunrise” … “it was beautiful early summer” … “the work commenced about five o’clock and was over by eight” … “at eleven o’clock began the burning of the bodies.” Interestingly, while Whitman wasn’t a war correspondent then, he later served as one during the Civil War, sending grisly dispatches to The New York Times from the war hospitals where he volunteered as a nurse following the publication of Leaves of Grass. “Song of Myself” is ultimately a transcendental celebration of the individual and the universal. But it is one infused with attention to the real word, that is to say, one grounded in facts.

Recommended

Nor’easter

Post-Op Appointment With My Father

Cedar Valley Youth Poet Laureate | Fall 2024 Workshop