The Craft in Conveying Characters’ Souls: An Interview with Rachel King

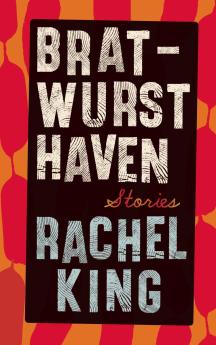

When I met Rachel King at the Portland Book Festival last November, there was something about her quiet presence, the way she watched people passing and seemed to really see them, that made me want to read her writing. She gave me a copy of her story, “Railing,” which had been published at One Story. From that first story I knew I needed to read more from King and so I was delighted when I got my hands on a copy of her forthcoming short story collection Bratwurst Haven (out November 1, 2022 from West Virginia University Press).

In Bratwurst Haven, King takes us into the complicated and yet ever-so-relatable lives of the workers at a Colorado sausage factory and in the community around them as they face the consequences of past choices and make choices that will have consequences long into their futures. Linked story collections can be a mixed bag, but King deftly takes us on a novelistic journey: we see a character in one story, then find them in another, further in their personal timeline from the point of view of a different character. Without being heavy-handed, King’s stories bring a close-up view on current issues facing people who are trying to make lives in the United States, with concerns such as lack of health insurance, mental health issues, managing a struggling business, divorce, and parenting. And while these stories may sound sad, the strong sense of resilience and King’s own love for her characters instill the reader with hope in the bonds people form with one another as well as in characters’ own individual persistence.

I was so happy when Rachel King agreed to an interview, because I wanted to know more about her writing process.

Jackie Shannon Hollis: In Bratwurst Haven your characters are so very real to life, and with small brush strokes you help us both imagine their physicality, but also help us dive deeply into their interior, even when the characters themselves aren’t aware of directly sharing that. From a craft perspective, how do you understand interiority and what tips do you have for new writers on how to access and express this on the page?

Rachel King: Thank you for your kind words. Interiority is complicated, but to put it simply, I think of it as a character’s soul, which Merriam Webster’s says is “the immaterial essence, animating principle, or actuating cause of an individual life.” That’s a beautiful definition; I’d never looked it up! So it’s what motivates a person, but also their essence, something deeper than motivation. Once I know the person’s soul, the story flows from there, and I find that if the problem with a story in revision isn’t technical, then it often comes from me not knowing my character well enough.

I think writing well about interiority starts with me loving interiority and wanting to write about it. Not every writer wants to focus on interiority, and that’s okay. If a writer wants to focus on it, I’d suggest them getting to know the characters before they start writing the story. For short stories, I often daydream about a character for a few weeks before I write; for novels, I always brainstorm about characters on a page, writing down characteristics or moments in their lives that may make it only indirectly into the narrative.

JSH: I was so compelled by each story, with a sense of urgency, wondering what was going to happen. And yet the circumstances of the characters in Bratwurst Haven are so familiar, so universal. How do you create this kind of tension? Do you write toward a specific ending when you begin a story?

RK: I’m so glad you felt urgency and tension in these stories. When I started writing seriously, I wanted to write about everyday moments and situations that seemed quietly charged, but I didn’t know if that was enough. Early on Amy Hempel’s story “Today Will Be a Quiet Day” gave me permission to write those kinds of stories, though I still had to find my voice and overcome some personal writerly faults to make my own everyday stories impactful. I learned to tighten my language and identify and heighten small shifts in characters and in-between characters. I learned when to write backstory as scene and when only a sentence or phrase would do. There are so many large and tiny skills and techniques that you acquire when you write for a long time, as you know. And I still have much more to learn. I’m excited for that too.

And no, I don’t write toward a certain ending from the beginning, though sometimes I realize an ending about three-fourth or so of the way through. Because my stories are character-driven, I think it would be a disservice to decide for my characters what they are going to do. I try to become these people and follow them and see what they do/what happens, then in revision I view them more as characters, not people, and tweak the stories accordingly, though I resist becoming too much of a puppeteer — I don’t want to edit out the magic.

JSH: How did this collection come about? Did you start off with the intention of writing a linked collection or was there a certain point when you realized you wanted to make it a linked collection?

RK: I wrote the first story in the collection “Railing” in summer 2016, then a year later wrote “A Deal,” then immediately started “Bratwurst Haven,” finishing it in spring 2018 along with an early draft of “Poker Night.” That’s the first time I thought that maybe I was writing a linked collection — but I gave myself the freedom not to, to just keep writing separate stories about these people in this place. Once I had eleven stories, I organized them into a collection, which was an intuitive process that I enjoyed. The collection begins with stories about characters in the factory, then moves out toward characters in the town, then moves back toward the factory in the concluding story. An editor and a peer reviewer at West Virginia University Press, after identifying some gaps, suggested that I cut one story and add two others before they published it. I enjoyed that process too, perfecting the breadth and depth of the collection.

JSH: Your stories are told both from third person as well as first person. Some are very small moments in time and some, most especially in “A Friendship,” which spans a lifetime, you cover larger swaths of time. Could you talk about the importance of this kind of texture and pacing in a short story collection?

RK: Sometimes I have an idea of a certain structure when I start a story. In “A Friendship,” I decided beforehand to write a story that would span a lifetime, and when I wrote “A Deal,” I challenged myself to write a story set in just one day. But in others I felt out the structure as I went along. I think each character and story demands a different structure, and I also think it can be important to vary the structure and length and POVs of the stories in a collection to engage readers. I didn’t order the stories chronologically — for example, the final story, “Bratwurst Haven,” ends right before the first COVID lockdown in the United States, whereas the

penultimate story, “Pavel,” expands into the first COVID summer — but rather intuitively, like you might have ordered songs on a mixed tape back in the day, or logically, based on when I want the reader to know facts about certain characters. I think the order of stories in a linked collection is more important than in a non-linked collection — like in a novel, the writer of a linked collection is determining the book’s overall pacing and tension by their rate of disclosure.

JSH: It’s always interesting to hear about a writer’s writing process. Where do you write? Do you have specific times that you write? What are your distractions and how do you move through them?

RK: Ten years ago my office job was giving away old desktops for free, so I took one, and have been writing on that ever since. I use a laptop for other work, and keep the desktop disconnected from the internet. Right now, I write on weekend mornings since I have a full-time weekday job. While writing much of Bratwurst Haven, I had two or three part-time jobs, so sometimes I’d write on a weekday morning or two, depending on my schedule. I’d love to write at least four or five mornings a week; maybe someday!

My biggest distraction is self-doubt, which is currently two-pronged: I doubt that I have a right to be an artist, and I doubt that my writing will be read. I’ve done the free-write morning pages from Julia Cameron’s The Artist’s Way off and on for the past five years, which has helped quell these two fears.

JSH: Let's talk about editing. How many passes did you make on these stories and what was the focus of the edits. I find that I have certain habits that I have to put a check on in the editing process.

RK: Yes, I agree; after you write a while, you start to notice your own quirks. For me, editing almost always means cutting words. I used to trim seven-thousand-word stories to three thousand words, now I trim four-thousand-word stories to three-thousand words. In general, however, each story’s editing journey is different, which fascinates me. In “Railing,” I expanded a critical scene, in “Strangers” I went from two point of views to one, and in “Middle Age,” I rewrote the entire story, starting where an earlier draft ended. Sometimes, especially if I didn’t write the first draft longhand, I’ll write the story longhand in a later draft, which allows me to see phrases or even paragraphs I need to cut or words I need to change. Revising can be chaotic and demanding, but it’s always interesting and challenging, and I love it.

JSH: Are you part of a writing critique group and if so, how did you find your group and what is the structure for looking at each other’s work? If you aren’t part of a critique group, do you have other ways of getting eyes on your pages and feedback on your work?

RK: I’ve been in small critique groups in the past — once or twice a month, we’d each submit a certain number of pages to be evaluated by the other members. But for Bratwurst Haven mainly one writer friend evaluated each story. I’d figure out most of the character, structural, and plot issues, then when I’d taken the story as far I could on my own, he’d comment on words or sentences or paragraphs or minor motives or moments that seemed off. Or I’d go to him with specific questions or issues and we’d talk through them. A couple other writer friends and sensitivity readers evaluated specific stories, but mainly it was him. My brother and spouse also read the stories as I wrote them, but as casual readers, not as editors or writers — they’d sometimes say something like, “Didn’t we visit a lake like that?” or “I liked that story best so far” but not really analyze them. I need readers like that too.

JSH: It seems that being a writer involves many hats and skills. There is the writing itself, and editing, but also the business of writing, of putting your work out into the world, seeking publication, then the process of marketing your book (social media and website and public readings and publicity). This is even more true when publication is with an indie or university press. How do you manage these different roles and what advice would you give to writers who are ready to send their work out?

RK: Yes, there are a lot of hats! For me, first and foremost, I try to keep my writing time sacred. I’m human so I don’t write every Saturday and Sunday morning, but most I do because I enjoy writing and have so many stories I want to tell.

If a writer is ready to send out work, I’d suggest looking at each publishing opportunity as an end in itself. Stephen King in On Writing suggests receiving credits in literary magazines before approaching an agent with a novel, but I don’t think it works like that anymore — writers often gain an agent at a conference or a prestigious MFA or because their tweet went viral. I’ve enjoyed the communities I’ve gained through publishing stories, but I wouldn’t recommend it as a stepping stone.

I’d also say that both writing and publishing may take two or three times longer than you may have planned or expected. For example, I received my first short story acceptance after five years of submitting. I’d also suggest being open to the unusual or unexpected — for me, after five years of sending out my second good novel, and many close calls, I decided to publish it through a hybrid press, where I paid most upfront costs. It has gone well — I’ve sold several hundred copies in less than a year — but I wouldn’t have imagined myself taking that path fifteen years ago.

As far as marketing goes, I’d advise others to lean into their strengths. For example, I’ve been using social media for only a few years, so although I promote my work there, I still don’t feel comfortable in that arena. On the other hand, I love to travel and meet people in-person, so I’m planning a tour when this book comes out, and trying to do many local events as well.

JSH: Thank you so much for writing Bratwurst Haven. The characters and stories have stayed with me. I’m sure it’s challenging to focus on new writing when you are guiding a new book into the world, but are you working on something new or do you have plans for new work?

RK: Thank you for reading Bratwurst Haven — and not only reading, but thinking so deeply about it, and wanting to interview me.

Right now, I’m working on a short novel where I’ve fictionalized the Red Heads, a 1930s women’s basketball team that traveled around the United States playing men’s teams. My short story on the same topic won an award a decade ago, and I’ve been trying to find the headspace to expand it into a novel ever since. It’s emotionally lighter than Bratwurst Haven, which has given me some relief. I’m going to return to writing about darker topics soon, so it’s nice to have this reprieve. I imagine many of us need something like that after the pandemic.

Recommended

An Interview with Ren Cedar Fuller

“Tracing the shape of real bodies”: An Interview with Frances Cannon

Becoming Visible