Lisbon Mon Amour

Originally blogged by The Best American Poetry, April 3, 2014.

It happens I am a fool. It happens I’m rather good at being a fool. It happens I am at my foolish best in Lisbon.

I wish it weren’t so. I wish I could report here to the committee that after ten trips in I could speak, say, ten words of Portuguese. I could name ten landmarks. I could name five restaurants and five bars. I could do more than identify a couple of churches and squares, a few signature dishes and luminary haunts.

It happens, yes, that I am a poet, and that the depth of things is the conceit from which I supposedly skate along in this world. The exploration of the unknown, the investigation of the other, the bona fide immersion into a foreign culture and its landscape––well, isn’t this the mortar of our métier? Isn’t this the inner lining that holds a writer’s mind together and keeps it warm? In no other foreign city, dear members of the committee, has sheer laziness burst forth from the seams and dressed me so; in no other foreign city has my mind felt so free.

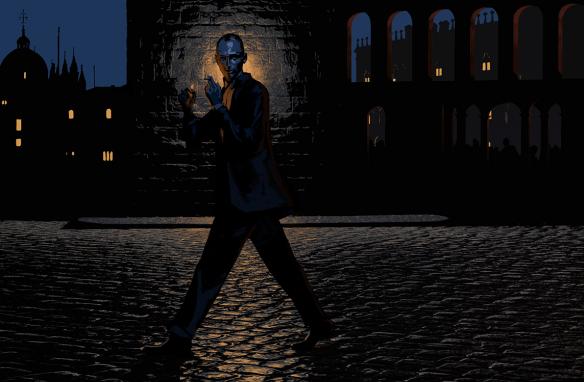

It is curious, to be sure––blasphemous, perhaps. But I wish not to have my porridge taken any other way. I wish to be bowled over by Lisbon the way I was the first time: with wonder. With ignorance. With abandon. “The insatiable thirst for everything which lies beyond, and which life reveals is the most living proof of our immortality,” Baudelaire wrote. Maybe he was right. For what lies beyond for this mortal hinges not, ultimately, on the understanding of Portuguese. Nor does it rest on an engagement with the people who speak it. It has no hankering for a rigorous knowledge of Lisbon’s history and its architecture. For this mortal walking the city has proved sufficient. Day and night, night and day. Year in, year out. New heels upon arrival, no heels at departure.

Sticking out like a big toe is the question: is this behavior in any way defensible? Can one justify experiencing a foreign city because of its language and because of its people, because of its architecture and its history, but from a distance? For much of it to remain a mystery, a grand mystery? Can one justify skimming a past as rich as Lisbon’s where aimless walking is the exclusive portal? Or is it sheer boorishness, for a writer, for anyone, to tether their experience merely to the physical landscape, to what is observed, to the sights and the sounds, the pulse and the pew? Can this and only this be the sole aperture––ten trips in? And what then, it must be posed, is particular about Lisbon that has allowed the mind to pivot in ways it hasn’t elsewhere?

I call on the human voice. The sound of the human voice is one I’ve always found comforting, no matter the language tunneling through it. And no matter how far I happen to have veered from central station, the sound of the human voice has always signaled that I am close to home. I know the species and the species knows me. What, however, are the consequences when a language and its tonal qualities do not fall gently on the ear, as Portuguese spoken in Portugal happens to fall on this Canadian's ear, this Canadian who has lived in New York City for the better part of his adult life?

I nervously propose that it is then that language becomes a buffer, and not a mediating tool. Language then becomes both the cacophony and the insulation from it. It becomes a separation fence between visitor and local, between the citizens of Lisbon and me. Yes, when in Portugal I should do as the Portuguese do. My default gaze, however, has turned inward. Walls have gone up and roaming of the interior gone down. Conversations heard in streets, in cafés and restaurants, immediately usher me into my own private world, a hovel, if one will. In Lisbon, my thoughts and me are one. We are as close as we have ever been. I have muted the noise that I’ve never been quite as capable of muting in places such as New York, Montreal, Tel-Aviv, Rio, Berlin, Buenos Aires or Paris.

It would be interesting, perhaps, to explore the psychological underpinnings explaining all this. I think it is far more interesting, however, to put Lisbon’s seven hills on the couch, its endless ascending and descending, its very step and stare. For the sense of circularity Lisbon manifests is one hard to avoid or contest. The physical experience simply permeates––everything. It courses through the mind as one walks from Baixa to Belem, and back. And so I wonder: is it possible, is it conceivable that the exposure to river views and city views that never seem to replicate themselves, the seemingly infinite number of fresh angles from which to absorb and process Lisbon, burnished by light that seems to shimmer and glimmer, reflect and refract, the Tagus River a body that never sleeps, does this experience of walking in Lisbon mirror, in some way, our mental state? If consciousness is an infinite reorientation, is the plethora of images experienced walking around Lisbon on an order higher than in most other cities?

Members of the committee: to walk is to love.

Howard Altmann’s second poetry collection, “In This House,” was published by Turtle Point Press in 2010. His poems have appeared in Little Star, Poetry, Slate, The Yale Review and elsewhere. A Montreal native, he lives in New York City. Howard was featured in North American Review‘s issue 299.2, Spring 2014.

Illustrations by: Clay Rodery, an illustrator who lives and works in Brookly, New York. Clay’s illustrations have been featured in the North American Review, most recently in issue 299.4, Fall 2014.

Recommended

Mercy

Eclipsing

Psychic Numbing