“That Man’s All Bad": John D. MacDonald’s The Executioners and the Melodramatic Imagination

About a third of the way through John D. MacDonald’s white knuckler The Executioners, Nancy tells her father that she disagrees with her English teacher: “She’s been telling us that good fiction is good because it has character development in it that shows that nobody is completely good and nobody is completely evil. And in bad fiction the heroes are a hundred percent heroic and the villains are hundred percent bad. But that man’s all bad.”

“That man” is Max Cady.

He’s despicable. A psychopath described by MacDonald’s narrative voice and his characters as an “animal.” He raped a fourteen-year-old in Australia, served time, and wants revenge against Sam Bowden, the former lieutenant who captured him. Cady’s logic is adrift in rambling references to the “word” and the “picture.” There’s a strange reckoning to him. He nearly beats a woman, Bessie MacGowan, to death; he wounds Bowden’s son Jamie, shooting him in the arm with a high-powered rifle (if not for high winds that day, he would have killed the boy); he poisons the Bowden family dog Marilyn and the children witness the dog’s death convulsions; he exerts power, tormenting children, women, and men who believe in reason and law.

Cady in not a character out of literature, to be discussed by readers of The New Yorker; instead, he prefigures Charles Baxter’s take on the melodramatic imagination. Nancy’s disagreement with her English teacher’s position is MacDonald’s way of positioning us within the irrational chaos dead center in The Executioners.

Cady is what Orson Welles would define as a Mr. Wu figure, a character in a play that the other characters discuss, building up his menacing gravitas, until he makes his appearance at the end of the first act (Welles himself played such a figure: Harry Lime in Carol Reed’s The Third Man).

Prior to the conclusion of MacDonald’s “first act,” Cady is only seen in retrospective exposition. The pleasant stasis of Sam Bowden’s life is disrupted as he tells his wife Carol about a strange encounter he had with Cady outside the law firm Bowden works for; he also informs Carol of his very first meeting with Cady, during World War II, and capturing him after the drunken sergeant had raped a fourteen-year-old girl. Carol, after hearing Sam’s description of Cady, relays to her husband the sight of a similar man she saw skulking about the fence line to their property; and much later, she calls Sam at work, telling him about the death of Marilyn from strychnine and how traumatized the children are over it.

Cady, for the first third of the novel, is a structured absence, his reputation growing by the tales told about him.

Finally he makes his first appearance onstage. Sam and Nancy are working on the family boat when Sam sees Cady, comfortably above them, leaning against a fence, drinking a beer, smoking a cigar. Sam confronts Cady who laughs and fires back, “Nice lines, Lieutenant,” voice full of taunting menace, referring to the boat’s lines and those of Sam’s coming-of-age daughter.

Cady then goes into his own nasty backstory, an expository tale full of animalistic power. After his release from prison, Cady kidnapped his ex-wife, repeatedly raped her, and left her with next to no clothes to crawl back to her new family. He had her sign “love letters” so she couldn’t press any charges. “You get the picture,” he says, implying this is what’s in store for the Bowdens. And as he prepares his exit, he makes the threat brutally direct, “That’s a real stacked kid, Lieutenant. Almost as juicy as your wife.”

All of the past Cadys, the stories told by Max and others, coalesce palpably into this traumatizing moment. The terror is now.

How can the lawyer protect his family?

He turns to the law, but since Cady has broken no laws, they can’t stop him.

They can only react, not act.

Therapists often describe cycles of abuse as a triangle, consisting of an abuser (in this case Max Cady), a victim (here, the Bowdens), and a bystander (those that know something is going on but can’t or don’t do anything: in The Executioners, the law). Often with time, the players within this triangle can shift roles. For example, a victim may become a future abuser. In J. Lee Thompson’s film adaptation Cape Fear, this is exactly what occurs. Bowden (Gregory Peck) wounds Max Cady (Robert Mitchum), captures him, and promises to send him to prison for life where he can “rot” in “a cage.” Peck’s Bowden relishes getting even, and lacks the self-awareness necessary to realize that he has sunk to the level of the psychopath. He has taken on Cady’s abuse of power, Cady’s reckoning.

By contrast, in MacDonald’s novel, Bowden contemplates killing Cady outright, but decides to work within the law to trap Cady and bring him to justice. Bowden has no final fist fight, tussle in a river, and playing possum with a rock, like the heroic Peck bringing down bad-boy Mitchum. MacDonald’s Bowden is an ineffectual hero. He sets the trap, falls asleep on his watch, sprains his ankle, and rushes in tears to rescue his wife. As Cady retreats he fires two random shots into the shadowy night.

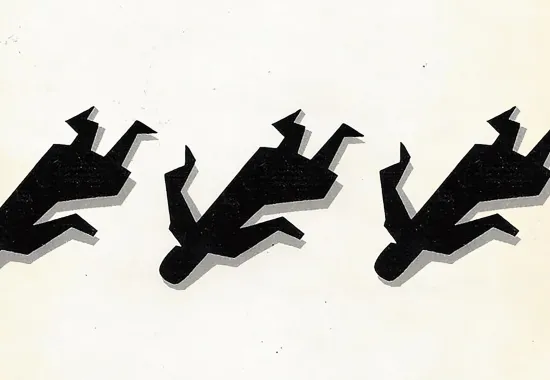

MacDonald’s finale inverts the novel’s opening. Cady’s built-up menace, his present-absence across the book’s “first act,” becomes a diminished retreat, a silent absence, an offstage death in the final act. His power is totally diminished. Like an animal, the wounded Cady runs from the Bowdens, and is discovered the next day, dead under some brush. There is no glorious “Made it, Ma, top of the world,” exit. Cady is no James Cagney as Cody Jarrett in White Heat going up in an atomic fireball. Instead, his body is brought back by troopers on a litter, and they “clumsily” handle it and drop Cady “face down in the damp grass.”

In the end, Sam Bowden’s world has returned to stasis. “I have come all the way out from under a dark cloud.”

But for Carol, her idealism is lost; she discovers, “There are black things loose in the world. Cady was one of them. A patch of ice on a curve can be one of them. A germ can be one of them.”

For her there is no stasis to fully return to; she has taken up permanent residence in the imaginative landscape of melodrama. The veil of innocence has been lifted from her eyes, portraying a world where rational logic can’t always protect you, a world where random things happen, terrible things, and life doesn’t always make sense.

Recommended

A Behind the Scenes Look at Art Selection and Cover Design for the NAR

“Doubling and the Intelligent Mistake in Georges Simenon’s Maigret’s Madwoman”

What the Birds Showed My Wounded Child, My Adaptive Adolescent, & My Wise Adult