Way Back Machine

Remember when you didn’t have to pump your own gas, and someone washed the windshield and checked the oil and your tires for free? Probably not.

But what was it like to be a young woman poet in the 70s, 80s, and 90s? How charming to use typewriters! To find writing advice or poetry criticism addressed most of the time to a man, using a male pronoun.

How, back then, did you find where to submit? The library sometimes had small press journals, something other than The Atlantic and The New Yorker, impossibly out of reach. Poet’s Market and Writer’s Market still exist, and assumedly people still use them. A copy from the library was probably three years old by the time the data was gathered and formatted, the book published and distributed. Chances were the editor they listed was no longer on the masthead of that journal.

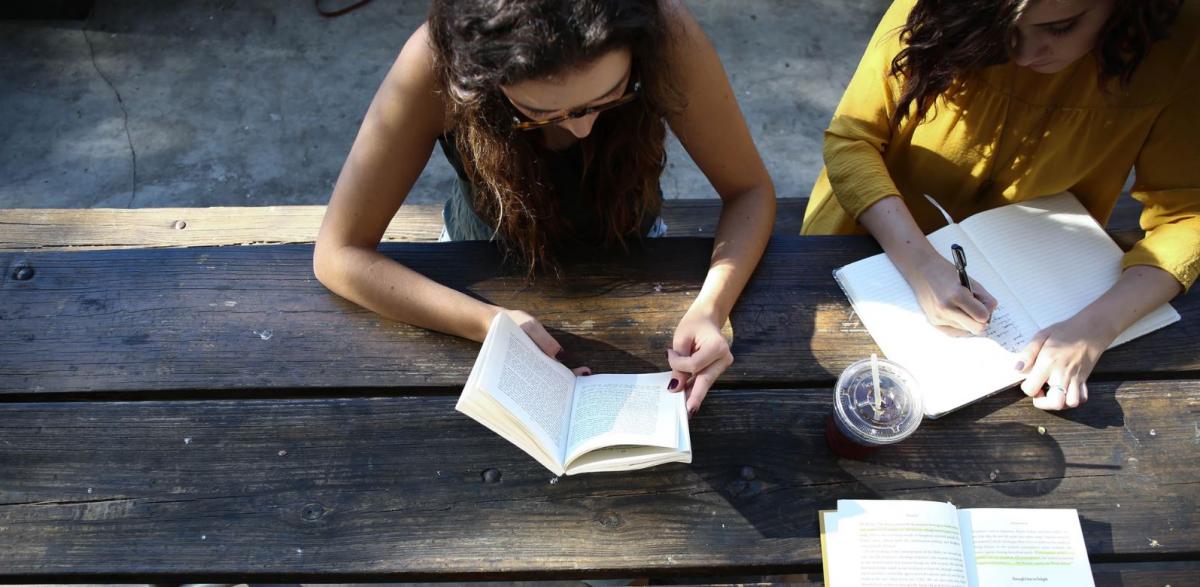

In Northern California, you could find some current information in Poetry Flash. Calls for submission there might be in that year’s ballpark. You could find literary journals to browse in places like Small Press Traffic. I did not find Small Press Traffic welcoming or illuminating, but I did find it. I remember going there with a friend, for encouragement, leafing through and taking notes in journal after journal, while the person behind the counter looked coolly on.

Once you found someplace to send work, you typed up copies or found a shop where you could get decent Xeroxes, stuffed four poems and a cover letter in an envelope, and then you went to the post office. There you weighed the folded submissions to know how much postage to put on the SASE and weighed it again with the outer envelope to know how much the whole package came to.

But the worst part of being a young woman poet in those days, for me, was having no community, no confrères (or sistahs). Few MFAs existed then, at least to my knowledge, and anyway, we had no money for those things. The master’s program at SF State was about $500 a semester. I started it around 1980 and stayed in it as long as I could, taking courses in teaching composition and semantics, despite being pregnant and then having an infant and a toddler at home. I finally handed in my typed thesis before the deadline ran out in 1986. But community didn’t happen. I was already old (in my thirties! imagine!), married, a mother. I left with my MA, even more isolated than when I began.

I’m sure there were people there who already knew what they were, what they wanted, what the poetry world meant. When asked, instructors gave me some reading lists—Bly, Simic, Dubie, Gilbert, Orr, Carruth—all great poets. No one suggested Plath or Sexton. They were hysterics. Atwood was lightweight. Bishop was, you know. Kumin? Clifton? Forché? Rich? I wanted to read work that would pull me in; yes, it would say, you are one of us. It didn’t happen.

I saw an ad in Poetry Flash for a poetry group not far from where I lived. After two meetings, however, the workshop disbanded. That’s when a friend suggested we start our own workshop. We used my husband’s photo studio in SoMa (then dumpsterville), despite the grungy locale and his work partner’s disapproval. The workshop eventually became the 13 Ways Poetry Group, still going strong after more than 30 years, now without me.

The Community of Writers at Squaw Valley was a saving grace. It’s still a source of inspiration and support, and then there’s the mountain air. The faculty poets who teach there work on new work themselves. It can mean a lot to suggest a line break or word change to a Galway Kinnell, to know that they are not gods.

It’s all different today. Maybe you take for granted today’s poetry climate where diverse poets—gays, trans, the differently abled, people of color, recent immigrants, and even impossibly old women are welcomed. Maybe you think the scale has tipped too far in that direction. In 1990, I reviewed a book called Spreading the Word (Bench Press) that revealed the acceptance strategies of sixteen solidly respectable print (of course) journals, all but two headed by men. It was not encouraging. In the next edition, in 2001, four of the twenty-one editors were women. Not very heady progress.

If I say women, once they get past a certain age, or the certain age, are invisible, is it ageism or sexism that makes them invisible? Once, at Bread Loaf, hanging with—I thought I was conversing with—two “fellows,” the top of the hierarchy at that conference except for faculty—one asked the other, “Can you imagine coming back here when we’re 40?” (I’m sure he meant as paying contributors.) They laughed; it was so ridiculous. I, a contributor, was 50 at the time. That was 20 years ago.

Would things be any different now? Maybe they would be more careful about who overheard them.

Recommended

A Behind the Scenes Look at Art Selection and Cover Design for the NAR

“Doubling and the Intelligent Mistake in Georges Simenon’s Maigret’s Madwoman”

What the Birds Showed My Wounded Child, My Adaptive Adolescent, & My Wise Adult