Narrative Tension: The Promises Writers Make

Not every jumble of events makes a story. Writers employ each element—plot, setting, voice, and more—to shape curiosity in the reader’s mind. That well-shaped curiosity poses questions that the writer promises to fulfill with their story. These questions infuse those jumbles of events and details with connection and meaning and push the story toward its purpose. All of this is narrative tension.

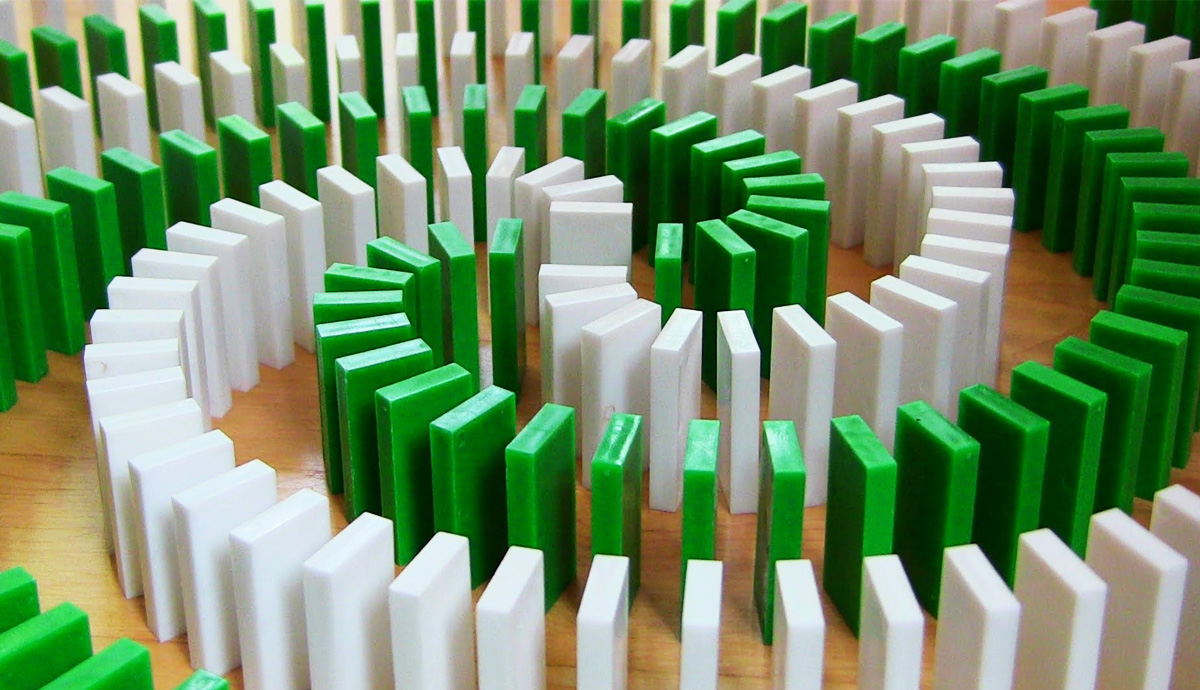

Picture a trail of standing dominoes with lots of twists and curves. What happens when you knock the first one into the second? If the dominoes are placed correctly, the first knocks the second one over, and that knocks over the next, then the next and the next on down to the long winding end of the trail. In fact, when dominoes are placed correctly, they have to fall.

Connection, momentum, and inevitability are intrinsic to narrative tension. Keep these concepts in mind while you read the anecdote I’m about to share. Ask yourself, Where is the tension coming from? What promises is the storyteller making?

Let me set the stage. For several of my daughters’ elementary school years, they took piano lessons with a man we’ll call Mr. Dale. He had a deep Carolina accent, a brush broom mustache like Mario from the Super Mario Brothers video games, and a boom to his voice that compensated for hearing loss he suffered from the crack of thunder after lightning struck him. At his house, he would welcome me with hearty claps to my shoulder and shouts of, “How ya doin’, Mama?” or “How ya doin’, sugar?”

One summer, Mr. Dale’s mother was ill, so he called often to rearrange lessons around trips to visit her. I assumed that was why he was calling the day this story unfolded instead.

“Sit down, sugar. Are you sitting down?” he started off, at full blare. “You know that little room off my studio? The one with the refrigerator in it?” He taught lessons in a small outbuilding behind his house. “Are you sitting down, sugar? Oh, Lord. You know that little room? I was thinking of painting it. Remember that little skinny guy, Steve Combs, who painted my house a couple years ago?” I probably did remember, but he didn’t wait for an answer. “I was looking for two gallons of paint back there. Are you sitting down?” Next, he went into his house to ask his wife, “Lona, do you know where that two gallons of paint is?”

And she said, “Albert. We got to talk. We got to get a divorce.”

In a well-told story, we crescendo to the end with a final, satisfying, “Ohhh!” as all the pieces click together and culminate in a surprise that everything before it foretold. In Mr. Dale’s story, we reach the end with a thudding, “Huh?” instead. Picture a domino trail with the pieces set too far apart, clacking to an unfinished end.

Why did Mr. Dale’s story leave us with that “Huh”? For one thing, his details did not relate to each other or to the final crisis. For another, whenever he urged me to sit down, he focused the oncoming danger on me, the listener. If I needed to sit to hear his news, then that news should affect me at least as much as it did him. As I listened, I scrambled to attach danger to the places and things he mentioned. The little room with the refrigerator, was there a nest of copperheads there? So close to where my young daughters practiced piano? The two gallons of paint, was the can nestled in a bower of shrubs with an escaped convict crouching beside it, evading capture? Armed and dangerous?

In writing workshops, drafts with underdeveloped narrative tension often trigger questions such as, “Why this? Why now?” or, “Where’s the urgency?” or, “Has this story earned its ending?” Endings that fail to connect to the tension a story builds evoke that “Huh?” rather than the “Ohhh!” writers aim for. These problems persist even when stories enlist other effective and engaging elements. Think of Mr. Dale’s quirky, vibrant voice; his specific, tangible details that anchored us in the scene; his constant remonstrances for me to sit down that indicated urgency. Still, his ending broke every promise he made in the telling.

A quick caveat for Mr. Dale: Humans experiencing trauma do not have to follow storytelling rules. He related a very specific chain of events in the order that they happened immediately before he got the worst news of his life. He didn’t owe us the satisfaction of denouement. His example, though, demonstrates how a story can be chock-full of good ingredients and still fail to cohere. A story needs narrative tension to glue elements together and drive them toward the story’s end.

Mr. Dale’s anecdote reveals the essence of narrative tension through its absence. Let’s zero in on its presence next. Narrative tension often piggybacks on plot and suspense, but we aim to understand it as its own discrete entity. To do this, we’ll examine narrative tension in three stories with radically different plot structures.

Forward motion is easiest to detect in stories of imminent and increasing danger, so let’s start with William Gay’s “Charting the Territories of the Red,” from his Time Done Gone Won’t Be No More collection. This suspenseful tale involves a river rafting trip that evolves into a brutal melee over the character Wesley’s machismo-induced reaction to jealousy. Here, events start out badly and end up worse. The plot arc depends on intensifying violence, and narrative tension derives from this escalation, following Jessica Page Morrell’s recipe for narrative tension, with “a character being threatened and transformed by a series of changes, and as the story progresses these changes become increasingly threatening.”[1] The defining question in readers’ minds is a breath-holding, “Dear God, what awful thing is going to happen next?” Everything that delays or delivers that danger fulfills the story’s promise.

The combination of revelation and forward motion sustains the reader’s tension/attention and binds the story’s actions together.

Even in this story of edge-of-the-seat peril, though, plot isn’t alone in conveying tension. Every element comes along for the ride . From the story’s opening, Gay braces us for violence, guaranteeing that we both expect it and react to it: a one-two punch of unease, and of narrative tension. Foreshadowing of Wesley’s volatility shows up through flashbacks near the beginning when we learn tales of his abusive past. Descriptions boost this ominousness, such as when Gay compares Wesley to “a sinister statuary,”[2] a fitting parallel for a character driven by what turns out to be a fatal lust for revenge, and again when he describes the river as, “[moving] under them, yellow and murmurous, flexing like the sleekridged skin of an enormous serpent,”[3] which is especially apt since the river literally delivers the characters into the conflicts that destroy them.

Thanks to the shape of the plot and these corroborating story elements, the culminating uproar of violence at the end feels like a natural outgrowth of what came before it—the fulfillment of the author’s promise. Readers experience the grisly finale with that hoped-for, “Ohhh!”—or, in this case, “Oh no!”—reaction.

The plot structure in Edward P. Jones’ “Lost in the City,” from his Lost in the City collection, looks nothing like the one in “Charting the Territories of the Red.” In the first paragraph, Lydia learns that her mother has died and pledges to come to her hospital bedside right away. Here she utters the promise of the story herself, assuring the caller from the hospital in three different ways that she’ll get there “‘soon as I can.’”[4]

“The relationship between the fiction writer and reader is, in some ways, tantamount to seduction,” says Bret Anthony Johnston, “the writer, via the plot, awakens a desire within the reader, and the longer that desire remains unsatisfied, the more intensely it burns.”[5] Anything that interferes with the incumbent expectation that Lydia will go to her mother’s bedside promptly, then, inflames the story’s tension. So we feel antsy when she delays, snorting coke and showering. When she finally calls the taxi, we’re relieved. Tension spikes again when the driver asks where Lydia wants to go, and she instructs him to “‘[j]ust get me lost in the city.’”[6] Maybe she’ll never get to the hospital.

Narrative tension is the source of all of a reader’s expectations as well as the agent that fulfills or dashes them. Lydia’s aimlessness is the final dasher of the expectation that the reader will see her reach her mother’s bedside at all.

As in Gay’s story, elements cooperate to increase tension. For example, at the moment of her mother’s death, Lydia is in bed with a man whose name she can’t remember. She has to page through her planner to piece together his identity. From this scene, we shift into remembered dialog from a trip Lydia took with her mother to the Holy Land. Lydia considers her naked bedfellow immediately before story recounts her mother saying, “‘I can’t believe I’m walkin the same paths that my Lord walked.’”[7] Next, in the story’s present arc, Lydia sniffs her first line of coke.

Sandwiching Lydia’s mother’s spirituality between evidence of Lydia’s corporeality creates tension by underscoring Lydia’s sense of unworthiness in her mother’s eyes. More memories of her mother sprinkle through the story and remind us of Lydia’s low self-worth. All these moments not only build the story’s tension but also drive us toward its purpose: Lydia grieves her mother deeply but cannot bring herself to do so with propriety because of her profoundly felt shame. The combination of revelation and forward motion sustains the reader’s tension/attention and binds the story’s actions together.

The last story, “The Littoral Zone,” by Andrea Barrett from her Ship Fever collection, presents yet another plot structure, one that begins in a moment in the past, travels a couple decades beyond it, and returns us to the past. In it, two science professors have an affair during a three-week summer program on a remote island and decide to abandon their families for each other after their return.

In the opening scene, the lovers are about to part ways and return to waiting families. The middle portion gradually discloses the lovers’ regrets over leaving their families, feelings they never admit to each other. The final scene shows the lovers before and after consummation, a scene which would normally carry at least a hint of joy despite the taboo, but our somber knowledge of their future regrets usurps the mood entirely.

As with the other two stories, narrative tension fluctuates along the sine wave of the story’s central question, which, in this case, is, Are these lovers happy together? Whatever shows happiness or discord about their decision to be together provides the tension and pushes us toward the ultimate discovery of their regrets.

Barrett uses omniscience to demonstrate the many ways the lovers’ memories align as well as contradict each other. This wavering plants doubts in the reader’s mind. Phrases such as “They both remember,”[8] and “They have always agreed”[9] establish moments of accord. They often remember details of events differently, though. For example, they remember much about their first conversation similarly, but they disagree on which day it took place. Small differences in their memories, which the omniscient narrator carefully doles out through the text, cue the reader to suspect potentially more significant differences beyond these.

In the closing scene, the omniscient narrator takes a step back and lets the reader experience the moments as if they are new, unfiltered by the characters’ recollections. We don’t get to compare the lovers’ same or separate memories. The details of their conversation, foreplay, and lovemaking follow one after another. Even in the absence of the characters’ retrospective feelings, we understand that the love we watch slowly budding will wither and die on the vine.

Point-of-view, in the form of an almost heavy-handed omniscient narrator, generates much of the narrative tension in the story, but, of course, it is not the only delivery system. The narrator points our way toward the couple’s secret regrets, and secrecy itself brings tension. The mention of the story’s title within the text boosts pressure, too. We are unsurprised to learn that the lovers’ “first real conversation took place on the afternoon devoted to the littoral zone,”[10] because one of them in an expert on it, “that space between high and low watermarks where organisms struggled to adapt to the daily rhythm of immersion and exposure.”[11] Later, the couple’s earliest happiness is described this way: “They swam in that odd, indefinite zone where they were more than friends, not yet lovers, still able to deny to themselves that they were headed where they were headed.”[12] The story celebrates this liminal space, and references to the littoral zone emphasize that fact: that the couple was happiest when the notion of sex was alive between them but before actual consummation and before they sacrificed the lives they knew.

These three stories vary in plot type, point-of-view, narrative distance, setting, tone and more, so narrative tension takes a distinct form in each one. In every case, though, in these stories and beyond, narrative tension derives from whatever leans a story forward and links scenes together with urgency and relevance. As Peter Turchi notes in his essay, “The Writer as Cartographer,” we enjoy giving ourselves over to stories “as long as we feel confident we are following a guide who has not only the destination but our route to it clearly in mind.”[13] Narrative tension is that guide.

[1] Jessica Page Morell, “How to Build Tension and Heighten the Stakes,” Writer’s Digest (November 17, 2010).

[2] William Gay, “Charting the Territories of the Red,” in Time Done Been Won’t Be No More: Collected Prose (Brush Creek, Tennessee: Wild Dog Press, 2010), p. 57.

[3] Ibid, p. 63.

[4] Edward P. Jones, “Lost in the City,” in Lost in the City: Stories, 20th Anniversary Edition (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2012), p. 140.

[5] Johnston, “What Every Fiction Writer Can Learn About Plot from That Lovable, Furry Old Grover,” in Naming the World, p. 203.

[6] Jones, p. 148.

[7] Ibid, p. 144.

[8] Andrea Barrett, “The Littoral Zone,” in Ship Fever (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1996), p. 48.

[9] Ibid, p. 49.

[10] Ibid, p. 46.

[11] Ibid, p. 51.

[12] Ibid, p. 52.

[13] Peter Turchi, “The Writer as Cartographer,” in Bringing the Devil to His Knees: The Craft of Fiction and the Writing Life, edited by Charles Baxter and Peter Turchi (Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 2001), 169.

Recommended

A Behind the Scenes Look at Art Selection and Cover Design for the NAR

“Doubling and the Intelligent Mistake in Georges Simenon’s Maigret’s Madwoman”

What the Birds Showed My Wounded Child, My Adaptive Adolescent, & My Wise Adult