Write What Scares You vs Trauma Porn

Two bad ideas about trauma have wormed their way into the world of nonfiction writing.

The first: If you write about traumatic experiences you’re a self-indulgent purveyor of navel-gazing. Someone who believes this might tell you in a writing workshop that your subject is nothing more than “trauma porn.”

The second: If you don’t write about traumatic experiences, you’re avoiding the only worthwhile topic. Someone who believes this might tell you to “write what scares you,” by which they mean, “find your most painful wound and punch it as hard as you can while I watch.”

Here’s how those ideas translate in practical terms: Be quiet. Entertain me.

"Go backwards in time and understand that America was founded on trauma: genocide, slavery. Go out into the world and understand that it’s our chief export, with our forever-wars in multiple countries."

Neither is a useful way for writers to think about trauma, yet they were the most frequent instructions I heard from teachers and students alike when I was in school, and I’ve heard them many times since in the various writing groups I’ve been part of.

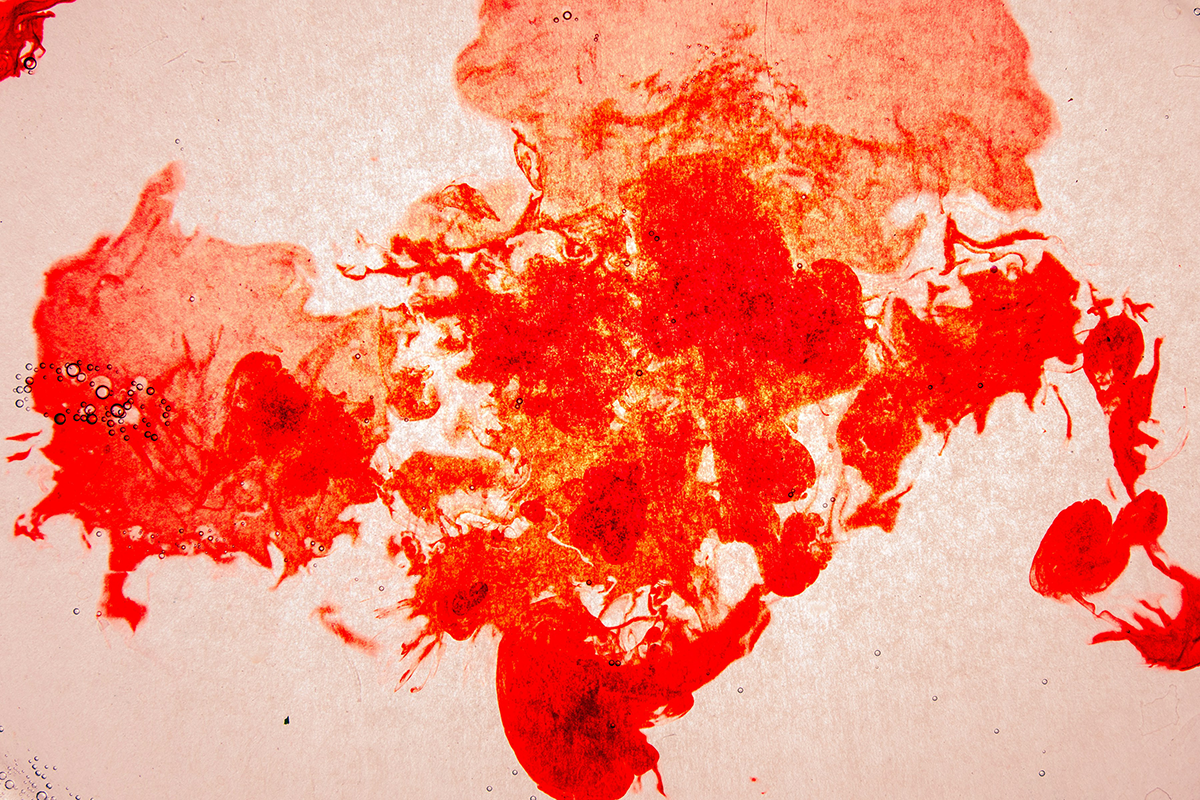

It’s impossible to satisfy both, but I tried anyway, and failed. It wasn’t until I thought about why they exist in the first place that I understood I could ignore them, which allowed me to finally write an essay about a frightening and physically torturous time in my life. That essay, "Bloodletting," will appear in the upcoming issue of North American Review and discusses contracting a deadly illness as a child while growing up in an abusive home.

The illness I suffered, ulcerative colitis, is often treatable if you catch it early. But the adults in my life told me it was everything except illness: it was growing pains, it was teenage laziness. When I mentioned I was shitting blood, a lot of blood, that was dismissed as a disgusting bid for attention. In other words: be quiet.

I fainted at school; it was hard to walk. Skin and bones. I was sent to a local hospital, where no one knew what to do for weeks. By a nurse’s insistence, maybe, or by that hospital’s wish to avoid a lawsuit–I don’t really know–I was sent to a larger hospital in a bigger town where a surgeon immediately recognized that I was bleeding to death. He took me from the intake exam directly into surgery where he cut out my entire large intestine and saved my life. He fitted me with a colostomy bag, and I spent the following days in the ICU and the following months in the hospital. I was fifteen.

Now the demands changed. I still shouldn’t talk about the things I wanted to–that I was afraid and ashamed and in pain. No one wanted to hear that I dwelled constantly on the fact that I had been dying and nobody noticed for a very long time. Instead I owed them a story about resilience and determination, the will to overcome. In other words: Entertain us.

I don’t know when, exactly, the symmetry between the messages I received as a child and the ones I received in my MFA program became clear. Maybe the stories my friends told of their own traumatic experiences piled up and with mine reached some necessary critical mass. All were terrible in their own unique specificity and made even more so by how easily the tellers could explain them into harmlessness.

It is clear to me now that we are all taught these two strange, conflicting messages, to be quiet or to entertain. And although they imagine trauma in opposite ways–either unpalatable or titillating–they both serve the same lie: that trauma is unusual.

But even if you grew up in a loving and attentive family, it’s impossible to avoid trauma, perpetrated as it is on a national scale. Take the system, for example, of allowing the sick to access modern medicine only if they have insurance, which they may not get unless they work. And if they can’t find a job or can’t work or get fired? What happens if they fall ill then? Well, then they just have to die. In other words: you don’t deserve to live unless you produce. Or, say, our collective decision to send children to school even though we are all afraid they might be murdered there in a mass shooting. Children face the possibility they could die every day–they prepare for it, even, they know how to sob quietly. The betrayal some must feel is that the adults in their lives sent them into that danger. Or our system of locking up more of our population in prison than any other country in the world. Or the ethos that says if you’re homeless, society has nothing for you, because protecting vulnerable people is not what society is for.

Go backwards in time and understand that America was founded on trauma: genocide, slavery. Go out into the world and understand that it’s our chief export, with our forever-wars in multiple countries.

It’s no wonder that we the people are increasingly unhappy. The suicide rate in the United States increased 33 percent between 1999 and 2017. Between 2008 and 2017, the percentage of adults in serious psychological distress rose for most age groups. Most of us are lonely. Symptoms of trauma, all. But like our dismissal of the horrors that caused them, none are widely acknowledged as a crisis or a tragedy, though they are both. No, these are simply personal matters. Remember, trauma is unusual.

Conventional wisdom peddles the idea that everyone would be happier if only we were more compassionate and better educated. But that is a fairy tale that avoids the hardest and most important step, which is acknowledgment. If we skip it, we skip seeing how we are affected by trauma, how we silence it within ourselves and in others, or how we force it into an acceptable package. It’s true for everyone, including writers trying to make sense of the suggestion that they avoid trauma porn or that they write what scares them.

So. Ignore the idea that you should be quiet. Likewise ignore the idea that your story may exist only if it follows a certain script, and even that you must write it for an audience. Instead, just consider whether you, like me, have had to endure things you shouldn’t have. Understand that you’re not alone. Then go from there.

Recommended

A Behind the Scenes Look at Art Selection and Cover Design for the NAR

“Doubling and the Intelligent Mistake in Georges Simenon’s Maigret’s Madwoman”

What the Birds Showed My Wounded Child, My Adaptive Adolescent, & My Wise Adult