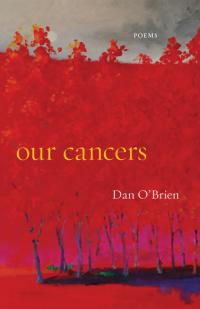

A Review of Our Cancers by Dan O'Brien

The title page of poet and playwright Dan O’Brien’s Our Cancers (Acre Books, 2021) announces that his latest book is not just a collection of, but a “chronicle in poems.” A chronicle implies more than mere chronology, promising a narrative, an official historical account of events so that they will be preserved for posterity. As such, a chronicle is defined by its relationship to and through time. Indeed, O’Brien’s 101 lithe, lyrical poems recount a period of time in which the poet and his wife each are diagnosed and treated for cancer. Like much of his other writing, some of which has graced the pages of the North American Review and Open Space, the poems are intensely personal, very much from the perspective of a singular “I” who emerges from the experience of pain, grief, and ongoing uncertainty with a new post-traumatic identity. In his recent collection of essays, A Story That Happens: On Playwriting, Childhood, & Other Traumas (Dalkey Archives, 2021), O’Brien explains that his obligation as a writer is “To tell others the truth, as skillfully as possible. To make art out of pain. To heal.” Our Cancers tells his truth not only skillfully but masterfully, making from pain a lasting chronicle of art that traces fragmentary moments of healing over time.

As a playwright, O’Brien is accustomed to dealing in dramatic time, which approximates the time of everyday life on the stage, the life of the body as it perceives the world moment by moment. Lyrical time slows the world down, lingering on the image, the interior experience of thought or emotion, or the sheer musicality of language itself. Narrative time speeds things up, able to summarize and move through history with the simplest of phrases. O’Brien operates within each of these modes with equal poise, beginning the book lyrically with the discovery of his wife’s cancer before leaping narratively back many years to September 11, 2001, when they lived in New York City and spent months breathing in carcinogenic dust he speculates may have been the origin of their diseases. Each of these opening moments is defined by a parallel experience of pain: “can you feel / my breast O / no O no // is all / I can say” becomes a memory of national tragedy, watching the towers fall as “An old woman fell / to her knees O // no O no.”

As a playwright, O’Brien is accustomed to dealing in dramatic time, which approximates the time of everyday life on the stage, the life of the body as it perceives the world moment by moment. Lyrical time slows the world down, lingering on the image, the interior experience of thought or emotion, or the sheer musicality of language itself. Narrative time speeds things up, able to summarize and move through history with the simplest of phrases. O’Brien operates within each of these modes with equal poise, beginning the book lyrically with the discovery of his wife’s cancer before leaping narratively back many years to September 11, 2001, when they lived in New York City and spent months breathing in carcinogenic dust he speculates may have been the origin of their diseases. Each of these opening moments is defined by a parallel experience of pain: “can you feel / my breast O / no O no // is all / I can say” becomes a memory of national tragedy, watching the towers fall as “An old woman fell / to her knees O // no O no.”

That echoing word O is a pure creature of poetry, peculiar to the lyrical mode, signaling that what is to follow in Our Cancers should be received in the spirit of the sacred. We are meant as readers to open ourselves to O and what it has to offer: the gift of human frailty, of mortality, of the possibility to be whole again in a broken world, however painful the process might be. O’Brien’s O rings loudly with the entire history of lyric poetry as a prayerful and reverent song, resonating with notes of the elegiac, a longing whose source is always grief. O is tinged with death, our first and original universal experience of loss and longing, and in O’Brien’s hands, it casts a spell on the page so that we hear and understand differently the words we find there. The O also becomes the lump itself, the cancer found in his wife’s breast and later in his own colon, and the painful O of 9/11 remains, not just grief over the American dead on that day, but the countless others worldwide who have suffered as a consequence.

The O returns here and there in Our Cancers to connect other pieces of pain and grief, namely around O’Brien’s memories of an abusive childhood, concerned that he will “regress to / what maimed us,” culminating in a moment unmoored in time and space: “Mother / O Mother / Mother I // call to / and from / nowhere.” Here, the O is accompanied by the source of another lyrical impulse, represented by the letter I. Nowhere can one observe these two poles of poetic creation in action as clearly as in Whitman’s well-known “O me! O Life!” when he asks and answers a (or the) fundamental question of existence: “The question, O me! so sad, recurring—What good amid these, O me, O life? // Answer. / That you are here—that life exists and identity, / That the powerful play goes on, and you may contribute a verse.” Our Cancers is not merely a statement of recurring sadness, it is the contributed verse, the assertion of being here, of life, of a new identity.

Our Cancers is a haunted book, with literal ghosts, poltergeists, apparitions, and angels, but it is also haunted in the way that all art is haunted, by traces left behind of the artist who created it in the first place.

O’Brien performs Whitman’s feat in a dream poem worthy of Berryman, hinting at his other abusive parent: “In the dream / he pronounces / he is pleased // that you suffer / I suffer even / our daughter // So I shatter / the mirror and slash / poor dad in half.” The O of suffering meets the I of a new father who “sings / the only lullaby / he’s ever known” against the specter of despair. The lullaby is an expression that the poet is still “somehow / believing // words can / cure this / curse,” which amounts to a faith in the power of art. Later, the poet asks, “Will these words / be my voice / haunting you.” The answer is, undeniably, yes. Our Cancers is a haunted book, with literal ghosts, poltergeists, apparitions, and angels, but it is also haunted in the way that all art is haunted, by traces left behind of the artist who created it in the first place.

Our Cancers presents other striking images and metaphors worth paying attention to for what they have to teach us (cancer as flies, chemotherapy as spiders), but a particularly apt one appears near the end of the book. For O’Brien convalescence is like being inside a remote cave listening “for the voice // raining like ash from / sky moon stars / that whispers // of birth / upon birth / O hear // O world / all that I am / hearing.” At first the voice is God’s or the divine, some cosmic explanation for the created world, including the darkness and suffering we must all endure, but with the phrase “O world” the poet performs a genuine magic trick, not ventriloquism or illusion, but truly becoming the whispering voice, the I, he had previously been listening for. The final entry in this chronicle of poems begins with a clever double voice: “There is beauty / I may not / recover.” Indeed, Our Cancers is itself proof that there is beauty, and the personal, clear-eyed recognition of uncertainty about the future is a necessary element to the poet’s post-traumatic identity. The secondary meaning in these lines, however, that there remains beauty in the world to be had that is not yet recovered in these pages, invites us to be alert to it in our own lives, just as the poet revels in the final life-affirming image of love and simplicity: “night falls / moon rises / daughter laughs.”

Recommended

After Hearing David Rothenberg Sang with Birds

Frothing Pink Poodle Droppings

Shoebox Reunion