For my twenty-first birthday I did not drink, slamming down boilermakers

at the bar, shots of Jim Beam backed with Old Milwaukee beer. I would journey

to the ballpark in Milwaukee, city rising from a sea of beer, to see the Brewers

and the Red Sox. From the grandstand, I would shout praise for Sixto Lezcano

of Arecibo, Puerto Rico and the Milwaukee Brewers, louder than the drunks

who yelled Hey, Six Toes as the crowd murmured between pitches, then yelled

it again every time he snapped a throw from right field on one hop to the plate.

Baraboo handed me two tickets, grinning behind his mustache from 1884,

railroad fireman’s cap over his eyes, nicknamed for the town in Wisconsin

famous as the birthplace of Ringling Brothers Circus in 1884. Baraboo played

banjo in a folk trio. At rallies, he sang a song legend says the partisans sang

to topple Mussolini from his balcony: O bella ciao, bella ciao, bella ciao, ciao, ciao.

Roberta was three weeks free of the asylum on the lake, where she sat for years

staring out the window with visions of sinking to the bottom. The nurses

snickered whenever she swore she used to work as a nurse on a psych ward.

She once escaped by calling a taxi. She helped me brush hospital-white paint

up and down the walls of my apartment, so I paid her with a ticket to the game.

Roberta brought a first baseman’s mitt for foul balls she was certain she’d

catch like perch yanked from the lake. Baraboo pulled to the curb in his VW

van with two soccer players from Germany who had never seen an inning

of baseball. He eyed Roberta and grinned through his dangling mustache.

Roberta has a secret, he said to the Germans. She hid her face, burning

in the pocket of the first baseman’s mitt. She’s a Red Sox fan, he said. Roberta

whimpered into the mitt. I became a Red Sox fan. Solidarity, the song says.

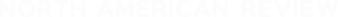

I sang hosannas for Luis Tiant of La Habana, Cuba and the Boston Red Sox.

El Tiante would spin on the mound like the stop sign I once saw spinning

in a hurricane on an island of wild ponies: saying stop to the hurricane god,

wrenched by wind, saying stop again. He showed his back to the batter, tilted

his head heavenward, wheeled and fired, the ball disappearing as an illusionist

would disappear rabbits at Ringling Brothers in the days of the elephants.

Maybe he saw his father in the centerfield bleachers, Señor Skinny, who tossed

his fadeaway for the New York Cubans, who taught his son how to grip the ball.

We saw the Brewers splinter bats and bicker with the umpire. They cursed

in the dugout at the pitcher with the shoulder blade cracked eight years ago.

Zero after zero rose on the scoreboard like balloons at the circus. Sixto lined

a single, but his teammates left him kicking the dirt at first base, a Puerto

Rican mystified by the snows of Milwaukee and the fans yelling: Hey, Six-Toes.

Roberta could not catch a ball hiding her face in the mitt. I prayed that Baraboo

would grab at a foul pop and topple from the grandstand the way Mussolini

toppled from the balcony when, the legend says, he heard the partisans singing

half a mile away. We filed out with the crowd, beer slapping in their bellies

like gasoline in the tank. El Tiante lit a cigar in the clubhouse after the shutout.

I never saw Baraboo and his mustache again. I would see Roberta, who won

back her nurses’ license and led the other nurses singing on the picket line.

Forty years later, I would shake hands with El Tiante and ask him if he could

remember Milwaukee in August of 1978. Four to nothing, he said. Ringling

Brothers lost all their elephants and collapsed the big top, but El Tiante

of La Habana still fires up cigars. He tells hurricanes to stop, and the wind dies.