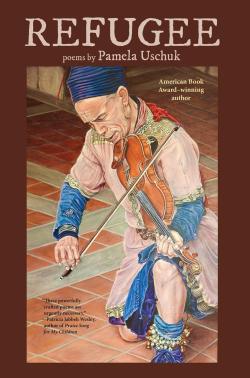

Seeking Refuge: A Review of Refugee by Pamela Uschuk

I doubt many readers would contest the notion that we live in a world in distress. Whether we focus on the war in Ukraine, racial discord, income inequalities, severe political rifts, threats to gender rights, climate change, or any of the other myriad dilemmas overwhelming our discourse, with that focus comes a throng of refugees—refugees from bombs and violence, refugees from drought, from disease, from hostile ideologies. Since all around us refugees seem to be fleeing from something, one must ask from what they themselves flee—and that it’s hard to imagine there is anywhere left one can go to find refuge.

I doubt many readers would contest the notion that we live in a world in distress. Whether we focus on the war in Ukraine, racial discord, income inequalities, severe political rifts, threats to gender rights, climate change, or any of the other myriad dilemmas overwhelming our discourse, with that focus comes a throng of refugees—refugees from bombs and violence, refugees from drought, from disease, from hostile ideologies. Since all around us refugees seem to be fleeing from something, one must ask from what they themselves flee—and that it’s hard to imagine there is anywhere left one can go to find refuge.

That is the dilemma at the core of Pamela Uschuk’s collection Refugee (Red Hen Press, 2022), a book of poems in four parts that beautifully and heartbreakingly renders a speaker’s quest to find either a safe place in a world deteriorating around her or a place from which to fight against the fall. In part one, the poem “Cracking One Hundred” shows us a view where “No wall can stop rising heat, the death of coral reefs / or the governor calling for the National Guard to secure the border,” while “Aggravated Child Death” renders the “deterrence” of immigration through separating children from their families as “our history of shame / hooked on the coiled razor-wire laws of inhumanity.” Whether looking at images of charring skulls or smoking cities, Uschuk demands we ask if we truly can “live remote / from city streets paved with bullet casings, / mass shootings in churches, refugee mothers in cages, / the beheading of girls sprayed from cable TV.”

While part one of the collection can be said to provide a window into a world on fire, Uschuk steps back in part two to a world on the brink, a speaker witnessing an ember ready to flare into inferno. We meet the speaker throughout as an “eco-poet” longing to glimpse the rarities of nature in poems such as “Giving Up,” where she seeks to witness the “sky-eyed snow leopard” and to hear “the thick screams of Himalayan eagles diving.” In her journey to see the manatee, she feels she perhaps has missed her chance as she is “baffled / by the singularity of their failure to appear.” The reader is forced to wonder through the book’s menagerie of birds, elephants, and squirrels whether they might inevitably face a world where the barred owls, moccasins, and moles might only exist in memory, and, if they are in fact seen, they will be just a reminder that their extinction is a conclusion long forgone.

Despite the power of the alarm and sadness created by the first two parts, the collection takes on a new intensity in the third part, strikingly titled “Liquid Book of the Dead” as the idea of healing emerges to the forefront. The section’s opening poem, “Healing Song For Surgery,” ends in the remarkable plea: “White wolf of healing, lap milk from moon shadows, / lope away from disease, from malfunction / to the center of the immutable, / sliced by fine tempered steel.” In “Pathology Report,” we see the brutal openness and trauma of “Day’s scalpel slices to widen the gap for hysterectomy / to remove all hysterical desire, flesh and mind / anesthetized, numb as a tomb,” but even in such invasiveness where “she was gutted by strangers who scrubbed her abdomen / of any trace of woman,” “her scream celebrates the strength to make a fist.” We come to realize that healing itself is a traumatic act, that just as an oncologist “make[s] you sick to make you well,” so too perhaps we must accept that the world will pass through brutal hardship as part of the process through which it repairs itself. As Uschuk writes in “Towards Wings,” “This time I pull the spear from my chest, / cauterize that terrible wound with burning feathers, / the hooked beak of the eagle buoyed by the wind.”

“... the poems arrive at a sort of sanctuary, a place of sipping coffee ...”

It is here, perhaps, the real strength of the collection coalesces: Uschuk is not a poet of pointing fingers even as the poems anger at injustice and violations. Instead, she focuses on the path that she and her readers might choose to move forward. In the fourth section, the poems arrive at a sort of sanctuary, a place of sipping coffee and watching birds at a “kitchen table / under which the sleeping dog of reason breathes.” In the stunning poem “Weather Change,” we encounter a prayer-like incantation as the speaker calls for clean air to provide relieving breaths for her cancer-ridden, veteran brother, women trying to be strong in Damascus and Kabul, mothers with premature babies, and the derelict and indigent. Uschuk reminds us in “Refuge” that we can be aware of corruption in the highest tiers of government and bear witness to the destruction of families in “our country that’s lost its heart” but still “sit with families / breathing the sweet tincture of mesquite smoke, watch / a girl’s head lean on her grandma’s t-shirt sleeve, resting / away from alternative facts beating truth blind.”

In the end, Uschuk brings home that the harsh truth is that sometimes “We are so dumb with loneliness / we cannot speak for wings we only guess,” and all we can do is “wait, holding tight our arms against news that darkens daily…nothing else to do but lean into one another’s sorrow, our disbelief.” Make no mistake: while Refugee does not paint a world in which there is no hope, it does paint the clear message that hope is the hard road, and the right one. In the meantime, the poems elevate love, companionship, and community as the refuges in which we gather our strength and remember what in this world is so beautiful that it demands we fight for it. In a world where it seems there is nowhere left to run, Uschuk’s Refugee offers more than just a vital shelter: it offers the road we need forward.

Recommended

A Review of Portable City by Karen Kovacik

A Review of Haircuts for the Dead by William Walsh

A Review of Birdbrains: A Lyrical Guide to the Washington State Birds