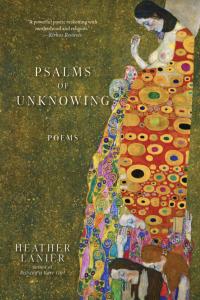

A Review of Heather Lanier’s Psalms of Unknowing

To read Heather Lanier’s Psalms of Unknowing (Monkfish, 2023) is to encounter a poet’s unflinching deconstruction of language—of received narratives in motherhood, faith, ability, even grief—and then to witness how such language might be reimagined, reembodied. In the prefacing poem, “Pumping Milk,” Lanier launches directly into essential themes through a catalog of questions, pulling the reader into that necessary unknowing—a prerequisite for engaging with the collection:

Is this what it means

to be a mother? The self, split

in two, like the body in labor?

Or is this just the tear

in humanity, even as we

shoulder-pad our denial—

always tugging us back

to the garden, to the beginning,

which wears the same

clothing as the end?

From its own beginning, Psalms of Unknowing refuses to offer easy answers. Instead, the poems embrace ambiguity, grappling with the uncertainty of the human experience across a varied terrain of topics, as the title indicates. But while psalm might evoke a musicality, a sacredness, the unknowing harkens back to an earlier meaning. Originally, the Greek word psallein meant to pull or pluck—and that’s exactly what occurs across this collection: an unraveling of assumptions, and, as we journey through each poem, the possibility of a new way of seeing, stitched across a full lived experience.

From its own beginning, Psalms of Unknowing refuses to offer easy answers. Instead, the poems embrace ambiguity, grappling with the uncertainty of the human experience across a varied terrain of topics, as the title indicates. But while psalm might evoke a musicality, a sacredness, the unknowing harkens back to an earlier meaning. Originally, the Greek word psallein meant to pull or pluck—and that’s exactly what occurs across this collection: an unraveling of assumptions, and, as we journey through each poem, the possibility of a new way of seeing, stitched across a full lived experience.

Written in four parts, Psalms of Unknowing is always upfront—and often humorous—in its irreverent yet urgent interrogations. “‘Free Bible in Your Own Language,’” the first poem in Part I (“In the Name of the Mother . . .”), continues the questioning: “Call me doubting Tom, but have you heard / my language? How I pepper the day / with oh shits of running late and roadkill?” Already, the poet seeks to redefine the meaning of “language.” This language has space for “shunyata, / that wide bell of a Buddhist word—emptiness . . .”—its “vacant pages” symbolic for ambiguity and doubt. This bible knows wildness, defiance—and although it questions, this vernacular isn’t asking for permission:

Upon what, you ask, is the book

written? Give me some space,

a quiet walk in the grass, unburdened

by your kiosk of Korean, Finnish, French....

With my footprints bending the blades,

I’ll write a psalm of unknowing,

knowing the sun will erase it, will call it back

into straight, green, speechless strands.

The subsequent poems in Part I also speak to pregnancy, to both fragility and resiliency—naming the losses that accumulate even as new life grows. Lanier reckons with what it means to bring life into a world such as ours, one that spins on “two turntables and a microphone-shaped gun” (“My Form of Yelling”)—what it means to bring a life “toward some stray / jagged thing / from which I must / with all I am / keep you safe” (“The World Turns Too Fast”).

These paradoxes of parenting in our modern world are further explored in the second section, “And the Child . . .” In Part II, Lanier dissects how such a world receives her own child, questioning our collective assumptions around disability. In “To the Comic Who Says Her Critic Is Missing a Chromosome,” the poet responds, “How many genes does it take to change / a heart?” But here there is room for a mother’s grief as well as her delight: “Your gloss-black pupils reflect / my stressed brow // easing into adoration. I see you / seeing me – mother struck / by the ancient wonder . . .” (“Your Eyes, My Daughter, Are Genius Caliber”). Here there is much to see that most of the world—in its “favor / of other bodies to be made more right”—doesn’t or won’t (“Psalm For Doctor Normal”). Here there is room for the holiness of it all: anger and adoration, despair and hope, the invitation to “rewrite / daily the world / with our baring” (“Etymology of Apocalypse”).

Part III (“And the Holy Unknowing . . .”) tackles relationships with self and others: political divisions and their saturation of our most basic interactions, entrenched patriarchal views, self-image in the age of the internet. Again the reader is offered new ways of seeing, of asking, of naming. In “Loving Thy Right-Wing Neighbor,” Lanier acknowledges the “inner crossing guard” present even in simple conversations—as well as shared human needs that exist simultaneously alongside cataclysmic divisions. (Similarly, in a brilliant use of caesura throughout the poem “Beyond Chitchat,” she explores the metaphor of quantum entanglement: “Einstein called it spooky / didn’t understand that two are sometimes one // despite light years between them What relief to know / we’re not alone so long as we’ve once been together”) These poems, such as the poignant “Beatitude for the Internet Age,” hold the tension, lay it bare in sacred spaces—churches, home, our inner lives—to proclaim:

Get low, not to repent but to press

your ear to the earth. Listen for the pulse

beneath the billions of you pacing. Hear it?

Soft, subtle—same word you cry for mercy.

Enough enough. But not this time

a begging. Enough enough—a blessing.

The collection’s final section, aptly titled “Amen,” builds on these themes, culminating in an expansive way of seeing, of being. In “Agnostic Says Morning Prayer,” Lanier is at her best in challenging—and reimagining—the patriarchal language and imagery of religion:

Call God a mountain. A mother.

I don’t know, Second Jesus,

surprise me. Melt the stained glass

in all these windows as we leap out,

breathe pine, are caught

by angels or very strong women.

This demand “to rewrite the language of heaven” reveals an expanded view: a way of seeing that winds back in acknowledgement yet also reaches beyond, ahead. The inherent holiness of nature is particularly notable throughout this final section, as the place where everything “wants no more than it is” (“News Fast [at a Monastery on the Hudson]”). Here, the hallowed halls lead back to the earth. Here we witness both the trading of “kidhood faith / for oaks and a void of sky” (“Ovulating in Church”) and a remembering of the “inner garden we were given / from the start” (“Eve”) . . . by a God “so big / we cannot find her” (“Packing for a Silent Prayer Retreat”).

The penultimate poem, “Canticle of the Ordinary,” is another returning—not only to nature as “living scripture,” but also to the mother and child:

Be delighted

in five-petaled stars.

Let them be

for once not prophets of death

or hope,

but canticles

of the ordinary, which seems

to be the most holy

we have.

The holy unknowing persists—among us, within us, and threaded through each section of Lanier’s insightful collection. These poems are individually trenchant, and their progression reveals an arc both keen and tender, spiritual and deeply human, specific and universal. To read Psalms of Unknowing is to uncover manifold gifts: an honest unraveling of held narratives and beliefs, space for uncertainty in our imperfect experience, and the invitation to reclaim what we once knew instinctively, as children—that unknowing is another word for wonder.

Recommended

A Review of When We Were Gun: A Narrative Poetry Cycle by Deborah Schupack

A Review of Apostasies by Holli Carrell