A Relentless Hunger – What Woman That Was: Poems for Mary Dyer

It seems I was born a woman

to be written about…

I picture my story woven with the others:

how thick, the text of our sufferings!

– from “Mistress Dyer Considers Her Memorial, Written and Unwritten”

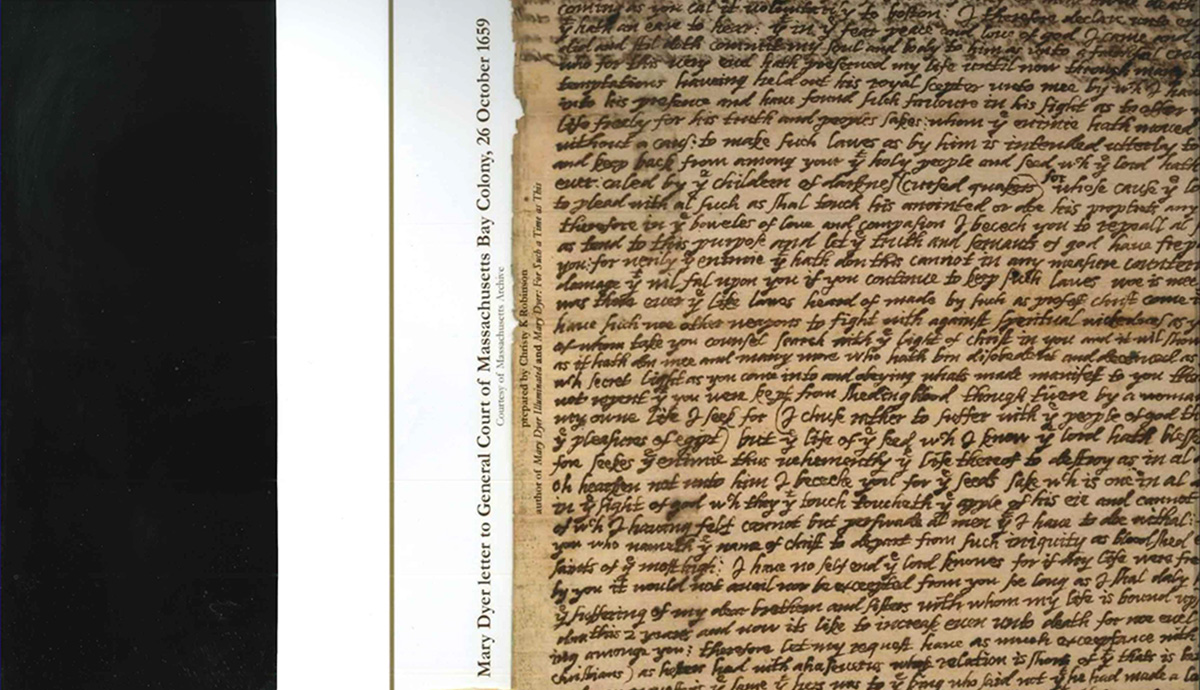

Before devouring What Woman That Was: Poems for Mary Dyer, I knew very little about the central character. I was aware of her name, had studied her as a brief paragraph in a survey American history class, and understood superficially her significance to Quakerism. Dyer was another forgotten woman. Another clear mind accused of “madness.” Another defiant heretic, silenced for public warning: “She did hang as a flag for others to take example of.” Another heroine who went willingly to her death, convinced of her revelations and desires, confident in her voice and dissent. Her death was a means to martyrdom, to the active preservation of a self and a narrative she had long sacrificed and suffered to discover. The poet Anne Myles unveils Dyer as one of many “courageous and troublesome women throughout history whose stories have been lost.” It is a gift to mine this stirring and necessary collection.

Before devouring What Woman That Was: Poems for Mary Dyer, I knew very little about the central character. I was aware of her name, had studied her as a brief paragraph in a survey American history class, and understood superficially her significance to Quakerism. Dyer was another forgotten woman. Another clear mind accused of “madness.” Another defiant heretic, silenced for public warning: “She did hang as a flag for others to take example of.” Another heroine who went willingly to her death, convinced of her revelations and desires, confident in her voice and dissent. Her death was a means to martyrdom, to the active preservation of a self and a narrative she had long sacrificed and suffered to discover. The poet Anne Myles unveils Dyer as one of many “courageous and troublesome women throughout history whose stories have been lost.” It is a gift to mine this stirring and necessary collection.

What astounds me most about Myles—so evident in What Woman That Was: Poems for Mary Dyer—is her language, her variance of form and line, the levels of textured surprise, the sonic propulsion and energy that carry these riveting poems. How she weaves so deftly and lyrically historical fact and reference with personal connection, with timely, vital questions about gender roles, power, hierarchy, and faith. She explores a woman’s individual, solitary place in New England’s and in America’s spiritual and historical arc. Myles also addresses themes of loneliness and grief, the search for solace, self-knowledge, and silence in increasingly turbulent, inchoate times. And such mastery of the persona poem, providing Myles the necessary distance for imaginative identification and enlightening dialogue. One example, from “Encounter:” “You listen to her strange tones mingled with your own. She sounds / like an ancient harpsichord, like a seagull screaming. She sounds like / the ocean booming, like a roomful of moans.” The sensory details alone are striking.

Throughout, I can feel the collective influences of Adrienne Rich (the political), Seamus Heaney (the historical), Emily Dickinson (the transcendent), and Marilyn Hacker (the “formally” complex), among others of Myles’ poetic forebears. What is most clear is Myles' obsession with the subject, her passion for Mary Dyer’s life and meanings, and in relation to her own. In “Invocation,” Myles writes: “You flash along the blurred edge / of my vision: a bright eye / is what I see, a raw vibrancy, / a relentless hunger / I want to sit down with.” (And yes, you definitely want to sit down with this hunger.) And later, “… I keep moving toward you, / watching my reflection / in yours, as you go searching / for what you lack; or long / for you instead, hidden figure of / another lost woman I can’t / let go of.”

At the close, Myles offers us “Monument,” a response to her experiencing Mary Dyer’s memorial at Earlham College in 2019. Beyond her awe for the reverberant stillness of the statue, The Poet, through Dyer, urges us to listen “to the sermon you preach in silence: / how to follow, to witness, to resist, / to walk the one road all the long way in.” A poignant end and crucial reminder.

Recommended

A Review of Portable City by Karen Kovacik

A Review of Haircuts for the Dead by William Walsh

A Review of Birdbrains: A Lyrical Guide to the Washington State Birds