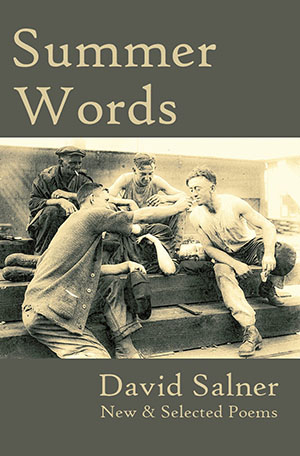

Poetry of Working People: A Review of David Salner's Summer Words

I have called David Salner “the Poet Laureate of working people,” and certainly he is that. Summer Words (Broadstone Books, 2023) contains many of his best poems about work—in various blue collar jobs as a longshoreman, iron ore miner, steelworker, cab driver, and garment maker—from his previous books: The Stillness of Certain Valleys, John Henry’s Partner Speaks, and Working Here. Yet in addition to powerful depictions of hard labor in Part Three, this gathering includes a wide range of impressive poems on various topics.

I have called David Salner “the Poet Laureate of working people,” and certainly he is that. Summer Words (Broadstone Books, 2023) contains many of his best poems about work—in various blue collar jobs as a longshoreman, iron ore miner, steelworker, cab driver, and garment maker—from his previous books: The Stillness of Certain Valleys, John Henry’s Partner Speaks, and Working Here. Yet in addition to powerful depictions of hard labor in Part Three, this gathering includes a wide range of impressive poems on various topics.

Part One has several memory poems about the poet’s early life. “My Father Catches Me Off-Guard” tells of a touching moment when he realizes how much his dad admires him and hopes for his success: “my father, this vulnerable child, walks towards me, / uncertainty lighting his eyes, two futures in every step.” “The Women of Paradise Township,” and “My First Slaughtering” evoke his boyhood rural world of rough work and others his hard-drinking kick-around life in the Sixties: “1968: The Diggers’ Place” and “For R.D. in the City of Poets.” While many of these poems are grim, others display the poet’s sharp eye, lightly held wisdom, and comic sense. In “What the River Said,” he turns Heraclitus on his ear and notes that “the river can never flow past / the same [philosopher] twice,” adding that had Heraclitus “stepped into a river, / any river, even once, / he’d be a better man.” Another favorite of mine from this section is “Cheerleaders Practicing in Eveleth MN.” As he watches the cheerleaders practicing, the poet conjures a small town world of intense blue skies and gum-chewing girls achieving a brief moment of grace: “when Sally Jongawaard flies in the air, / she knows that whatever else in the rest of her life / could go wrong, and probably will, the arms / of those girls from Eveleth High will be there / beneath the stone-cold blue of the sky, the sober sky, / will always be there, locked in a basket to catch her.” That added “sober sky” is the perfect note to suggest how poignant this moment is within the larger question of what fate has in store.

Part Two includes some fine pieces about the poet’s life as a worker, “A Calm is No Joke” and “Every Cab Driver Dreams,” as well as others that evoke some of the horrors faced by working class radicals, as in “Frank Little in the Big Sky State.” The author’s abhorrence of execution is seen in “The Hanging of Ben Harden” and “For Martin Bergen, Hanged as a Molly Maguire.” One of his briefest poems, “Death Penalty,” quoted here in its entirety, captures the harsh irony of one human taking the life of another: “In a book of Maya drawings / I saw the outline figure of a prisoner / who has been condemned to death. / He stands before the great ruler / and tears float like feathers / around his face. The two men / are identical / except for the tears.” Another understated poem of wry humor, “Lou Gehrig at the MDA Clinic in Morgantown WV,” shows the poet eying a poster of Lou Gehrig in his prime leaning on a baseball bat, noting how when we are healthy and fit a certain ease accompanies all our actions: “And there is not / the slightest suggestion of a crutch / in the way he leans on the bat.” We know, of course, that “the disease that will bear his name” lurks in his future. A kind of Coda to this poem is “In a Drugstore” where the still young poet tries out a cane for size.

As always in Salner’s poems, the job is described with precision…

As I stated earlier, the poems in the final part of the book feature a series of working class poems that speak with total authority about difficult and dangerous jobs, including “Waterfront Memoir:” “I scrape out ancient oil tankers, / breathe fumes all night until I’m dizzy. / I can barely climb the steel ladders /slick with condensate.” In “Furnace,” he recalls the lethal threats of an open-hearth mill where one worker and his brother after him fell into an “ankle-deep puddle” of molten steel. Two of the poems, “Monongah WV” and “The Seventy Ninth Miner,” deal memorably with mine disasters, the first killing at least 360 and the latter 78, as this moving poem narrates how a boy’s mother intervenes and saves her son from being the 79th victim of the explosion. Other gripping poems are set in the Iron Range of Minnesota and the Salt Flats of Utah where mining for Magnesium (“mag”) is the task at hand, creating a kind of fellowship among the workers (some of them convicts who hate the work but do it for “key privileges”). As always in Salner’s poems, the job is described with precision: “We cast mag into ingots slippery as brine / and grab them with steel handles. / We stack ingots until our coveralls / are caked with salt—so we can make / mag cheap enough for pop tabs / and racing wheels. Shift after shift / Mag sucks its value from us, / but we are the ones transformed.”

The title poem, “Summer Words,” is also set in the Iron Range, home, the poet notes, of Bob Dylan, but rather than mining mag, this one is about the poet and his friend Brian “who had a chain saw / and a couple of acres of spruce to stump.” The job was arduous and the weather bitter cold: “In Northern Minnesota / the work will get you quicker than the cold / which is, as Plutarch said, so serious / that words congeal as soon as they are spoken. / Those are the kinds of words we shared / on the Iron Range. Winter words.” After Brian sells the wood, he joins the National Guard; later they meet in a bar to talk. Plutarch had predicted that one day the words “would thaw out / and become the words you need. / For hours, we spoke those summer words.” This lovely poem is representative of much of Salner’s best creations: nitty-gritty telling detail, a compelling narrative, camaraderie among working people, a philosophical dimension, and the way, as with all truly accomplished poems, the lines, on repeated readings, keep yielding more meaning and pleasure. David Salner is a poet to treasure, and having much of his best work in a single volume is a gift to all lovers of serious poetry. ⬤

Recommended

A Review of When We Were Gun: A Narrative Poetry Cycle by Deborah Schupack

A Review of Apostasies by Holli Carrell