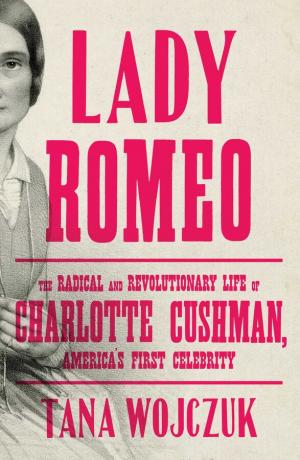

Lady Romeo: An Interview with Tana Wojczuk

Jeremy Schraffenberger: First of all, Tana, congratulations on writing this fascinating book, Lady Romeo: The Radical and Revolutionary Life of Charlotte Cushman, America’s First Celebrity. How were you introduced to Charlotte Cushman, and what initially inspired you to dig deeper in her as a subject?

Tana Wocjzuk: I’ve always been fanatical about Shakespeare, and I first encountered Cushman while researching another book about American Shakespeare. When I discovered that she was famous for playing men’s roles, and that she lived openly with female partners, I wanted to know more. Not just why she was so famous, but how her celebrity forces us to reconsider nineteenth-century America and our culture. I also love adventure stories, but as a girl felt like only boys got to have these adventures. But here was a woman who, like Viola in Twelfth Night, transformed herself into a man (onstage at least) and was able to live courageously and fearlessly in public at a time when women could not even go to college. Her life seemed like a wonderful adventure story, and representation—of women, of queer people—in the stories we tell about our history has always been important to me.

Tana Wocjzuk: I’ve always been fanatical about Shakespeare, and I first encountered Cushman while researching another book about American Shakespeare. When I discovered that she was famous for playing men’s roles, and that she lived openly with female partners, I wanted to know more. Not just why she was so famous, but how her celebrity forces us to reconsider nineteenth-century America and our culture. I also love adventure stories, but as a girl felt like only boys got to have these adventures. But here was a woman who, like Viola in Twelfth Night, transformed herself into a man (onstage at least) and was able to live courageously and fearlessly in public at a time when women could not even go to college. Her life seemed like a wonderful adventure story, and representation—of women, of queer people—in the stories we tell about our history has always been important to me.

JS: You call Charlotte Cushman America’s first celebrity. Why is she an important person for us to know about today? What can we learn about our contemporary world from her life and work, especially perhaps in the United States?

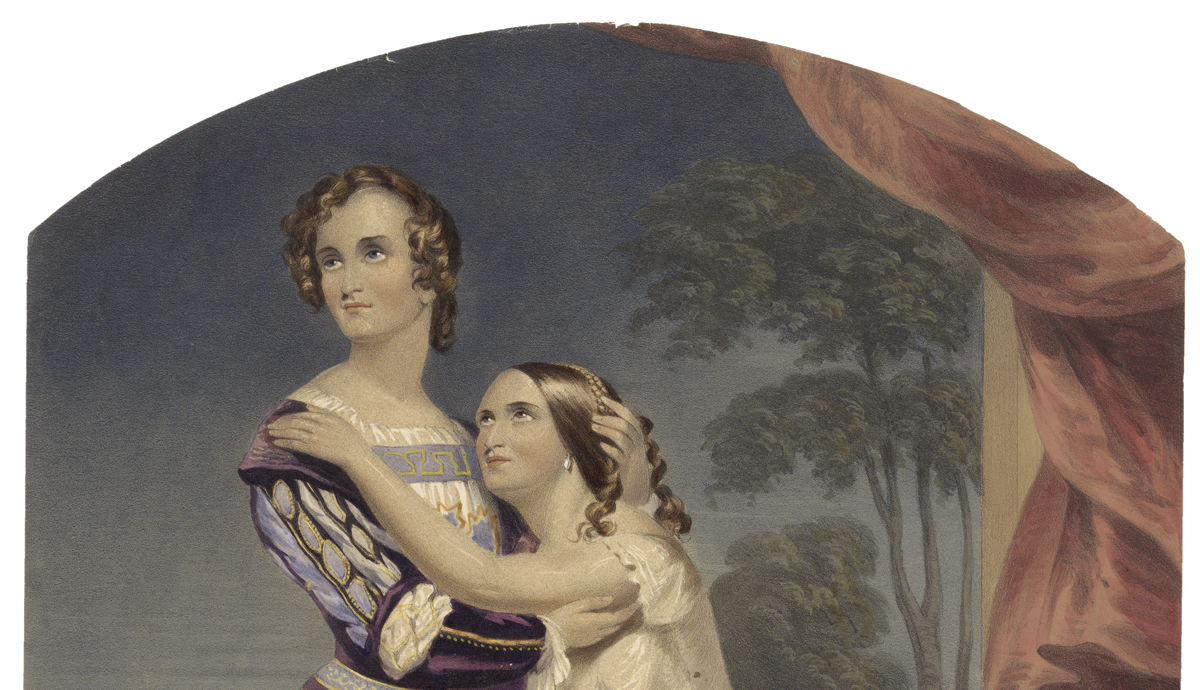

TW: When Cushman was born, in 1816 in Boston, America had no artistic culture to speak of. In Europe, it was thought of as a backwater, a “nation of campers.” Just as Cushman was making her stage debut, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Bronson Alcott, and others in the “Transcendental Club” were meeting to discuss why there were so few American Geniuses. They and many others, including Walt Whitman and Alcott’s daughter Louisa May, saw this genius in Cushman. But she wasn’t appreciated in America until she got the European stamp of approval. (She became famous in England for playing Romeo with her sister as Juliet.) One of the things we learn from her story is that the idea of gender as a performance was recognized in the nineteenth century, but also that gender norms were tightened after the Civil War and the rise of Victorian morality. I think of my work as a historian as a kind of “ret con” (as they say in the comics), where a shift in how we view history transforms how we see ourselves today. We are not just the product of stuffy Puritans. Audiences loved Shakespeare and they loved this powerful, ambitious woman. Our culture was not created only by educated elites but by the working class.

JS: Lady Romeo is a book rich with sensory detail, the writing itself is evocative with impressive narrative profluence. At times, reading it felt more novelistic than I’m used to finding in historical biographies. What tips, tricks, or techniques would you offer to writers wanting to craft artful nonfiction prose like your own, especially perhaps when the writing requires deep research of the kind you’ve done here?

TW: I’m glad it seems that way. That level of detail accrued over a decade of research, and though I want it to be known that it is deeply-researched, I also wanted readers who knew nothing of Cushman to fall in love with her. When I am writing I look for those sensory details and pile them up over many years. I also traveled to many of the places where Cushman lived and worked. For example, when I went to Rome I discovered that her first home was on the Corso and her second on the Via Gregoriana, meaning that she literally moved up the hill to one of the tallest points in the city as her celebrity grew. I also saw that she lived just a few doors down from the Villa Medici, where the ancient scions of Italian culture lived and controlled the city. One great tip is to keep track of your subject’s networks and to plunder their journals and letters for any mention of the people, places, and events you are writing about. Travel writing was big in the nineteenth century, and the travelogues of Dickens and others were a wealth of information. I tried not to rely too much on secondary sources, because I knew that the material I found exciting might not be quoted there

JS: The narrative shape you’ve given to Cushman’s life in Lady Romeo seems absolutely perfect for the stage or screen. Are there any discussions about adapting it?

TW: My editor Julianna Haubner made some great early suggestions that helped me shape the book into a more cinematic, three-act structure, and inspired the opening line of Chapter One. It makes sense to think of Cushman’s life in terms of an exciting adventure story with cinematic arcs and tensions, because it unspooled that way! But I also wanted to show how her life, and her work itself, challenged the traditional narrative arc. So I tried to show not only moments—like her unlikely triumph in London—that felt made for Hollywood, but also scenes like Henry James narrowly missing seeing Cushman perform as a child, that comment on how we narrativize our lives in retrospect, and how those narratives both falsify and help make sense of who we are. We are working with a wonderful film agent and I’ve been in conversation about adapting it for stage and screen.

JS: You’ve already mentioned having done a tremendous amount of research to write this book. As a writer, what are the joys of such research? What archives and collections did you consult? What were some of your most useful and reliable sources? I’m always interested, too, in learning about the surprise discovery. Did you find anything unexpected or rare that allowed you to fill in some historical blanks?

TW: Ah! I love reading detective stories and I get to feel like a detective in the archives. In the Houghton Theatre Library at Harvard I talked to the librarians and discovered that they were in the middle of digitizing tens of thousands of documents, but many were still unsorted in card catalogs and miscellaneous files. So I requested and read as many of these as I could, looking for unspotted gems and in one I found a cache of letters from Longfellow to Cushman, asking would she please star in a play he was writing for her! I realized quickly that published material from the nineteenth century was not necessarily reliable, as it is subject to the biases of the time. Letters were the most reliable, but nineteenth-century writing isn’t easy to read, and sometimes letters were written in pencil on tissue-like paper and cross-written with new lines written over the old ones. Whenever possible, go in person to the archive or to the actual historical site. Ask the librarians, and know that archives are created by people and they are idiosyncratic, each one works differently and is organized around slightly different principles.

JS: In part, Lady Romeo tells a history of American theatre in particular that parallels the development of American culture in general. In what ways does Cushman herself seem to embody a kind of artistic declaration of independence in a time when the United States was anxious about its cultural standing in the world?

TW: The nineteenth-century American theatre was a microcosm of the country as a whole. It was still segregated—by race, class, and gender—but it was the primary means of entertainment and everybody went. The “gallery gods” in the cheap seats up near the ceiling would throw food at the actors and the wealthier people below them if they didn’t feel the Shakespeare was good enough. Even though literacy rates weren’t high, working-class people understood and loved Shakespeare. I think that performance is essential to this understanding, and I worry about the state of Shakespeare festivals post-Covid. Cushman was a massively talented actor but she was also intelligent. I have a bit of training in dramaturgy and tried to approach her as a dramaturge might, looking at how her choices of where and how to give her lines changed the audience’s understanding of the text. Actors weren’t just vessels for the playwright, they were critics themselves and Cushman helped shape Americans’ understanding of female ambition (Lady Macbeth), masculinity (Romeo), and even prostitution (Nancy).

JS: Finally, knowing Charlotte Cushman perhaps more deeply than any other living person, you are likely in the best position to speculate about what she would have to say about 2020. How do you suppose she would react to our contemporary world?

TW: I’d say there’s a small but passionate few of us who know her story, and I’m hoping now there will be many more! But I do feel like I got to know her well, living with her for all these years. I think she would have been vocal about queer and trans-people’s rights. She tended to keep her work and personal life separate, but she also didn’t shirk when she felt that courage was called for, so she would likely be using her platform in more direct ways than she could in the nineteenth century. She revered Lincoln, and I think she would have ridiculed Trump, exactly the kind of bumbling, power-mad fool Shakespeare himself held up for scorn.

J eremy Schraffenberger is editor of the North American Review and a professor of English at the University of Northern Iowa.

eremy Schraffenberger is editor of the North American Review and a professor of English at the University of Northern Iowa.

Author photo by Adrianne Finlay

Recommended

An Interview with Ren Cedar Fuller

“Tracing the shape of real bodies”: An Interview with Frances Cannon

Becoming Visible