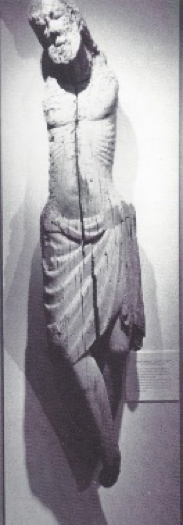

It seems incredible now, but as kids, when the six of us had the run of our old house on Summit Street, art was rarely, if ever, damaged. African pieces remained on their pedestals and rubber balls missed the Kunisada actors hanging on the dining room walls. Our Spanish Romanesque Christ, mounted between floor length windows in the living room, never once opened his eyes in consternation at our commotion. Over life-size, arms gone, his head remained bent in sleep as it had for centuries.

It seems incredible now, but as kids, when the six of us had the run of our old house on Summit Street, art was rarely, if ever, damaged. African pieces remained on their pedestals and rubber balls missed the Kunisada actors hanging on the dining room walls. Our Spanish Romanesque Christ, mounted between floor length windows in the living room, never once opened his eyes in consternation at our commotion. Over life-size, arms gone, his head remained bent in sleep as it had for centuries.

For my parents, I believe there were similarities between raising kids and collecting art—the commitment to protect, the patience with vulnerability, the respect for individuality. When new pieces joined our household, the sighs of relief were almost audible: from wood, from clay, even stone. They would have restoration and sanctuary. Goya prints were matted and framed, African and Pre-Columbian sculptures were carefully cleaned. Their new homes became the plexiglass cases Pa constructed with epoxy glue.

We took in stride the constant activity accompanying and accommodating an expanding collection: the rearranging, re-hanging. As the years progressed and more objects entered our home, the fellow from Burgos remained my favorite. He spoke to me. I have no idea if he had the same effect on any of my siblings, but from the beginning, his riveting presence became integral to my visual well-being—the swag on graceful hips, the tranquil harmony. I loved him for what he was: damaged, worn, softened by time. His genesis might not have been so likable: the sharp edges and distinct planes of the creator’s chisel, the polychrome, the reality of religious purpose.

In my last year of high school, while writing my senior paper on the Gutenberg press, I audited a history of typography course taught by Professor Harry Duncan at the University of Iowa. The next year, first semester of college, my schedule included his ‘hands-on’ typography class, an elective amid the string of boring requirements. When Professor Duncan learned of my poetry, he encouraged me to hand-set a booklet of poems. Christ from Burgos, one of four in the collection, was written in my mid-teens.

It’s been years since I last looked at the poem. Now, on rereading, I’m shocked. As a young person writing, I had neither religious knowledge nor the associated vocabulary. The inferences within the naïveté of that poem are astonishing: the decline of faith, corruption, resurrection, and hope. It goes without saying I knew little of these concepts, if anything at all.

Christ from Burgos

Slain by man, carved by man, his home was

once the church altar,

Many, many years ago.

Your church was destroyed, you were buried.

The bugs and the worms ate their way into man,

Many, many years ago.

Uprooted from his grave, golden as the dirt

herself,

Man Came.

Many, many years later.

Once again you hang on a wall, old and pained,

your arms gone, your eyes closed heavy with sleep,

your ribs eaten by worms and aged by time.

Now.

Lost in his quiet face is the grief yet hope of

all man.

Still.

May I rub my fingers through your dusty ribs?

Yes.

You, you with your peacefully quiet face, why,

why don’t you cry out once in your dreams!

Open your ancient eyes, just once…to me.

When?

At the age of fifteen or sixteen I was describing what I saw in that piece of wood—fragility caused by the passage of time. Those ‘inferences’ were accidental by-products of youthful writing. That’s all.

But why so many worm holes, why so much dust? As a child, I’d seen similar crucifixions in our travels across Castilla and Catalonia, Romanesque pieces in near perfect condition, still shiny with paint. To this day, our Christ’s physical deterioration remains entangled with my poem, the Prado Museum, and my youthful fascination with the painters Pieter Bruegel and Hieronymus Bosch.

That winter in Madrid, when Pa picked us up from Colegio Británico, the English grammar school my brother, Leo, and I attended, if time permitted, he’d circle back to the museum for another quick look before returning home for the mid-day meal. Wearing our coats and hats, we’d follow him through the chilly passages until he came to the Greco or Velasquez he’d abruptly left—realizing the late hour, realizing we’d be waiting at the school entrance, playing hopscotch on the pavement. Standing patiently in one of the painting galleries, we watched as he resumed his observation. With his left eye squeezed closed, the index and third finger of his right hand moved horizontally in space, blocking out a chair rung or a spot of light on the ruff. Turning vertically, they concealed a crucial length of drapery, or the perpendicular alignment of a desk and window in the background. Finally, stepping back, smiling, he shook his head in silent amazement.

After, as promised, Pa took us downstairs. Leo and I were drawn to the Dutch painters, especially Bosch, and with typical childlike curiosity we moved in as close as possible. We created work for the old guard, with his missing teeth and mended gray uniform. Straightening up to his full height, he approached, his voice serious and smelling of garlic. We pulled back before our cold noses touched those fascinating scenes.

A leaking church roof and dripping water was the obvious explanation for the crumbling wood, but why not interment? Even feisty Faustina, my family’s household help during our time in Madrid, even she would not have come up with such a wild possibility. Maybe Hieronymus Bosch wouldn’t have either.

The scenario emerged organically, pulling itself forward from the distant past, from an unknown, remote corner of Burgos province. A rural churchyard gathering of baying animals and devout, frenzied peasants. A Technicolor display of religious fervor: strange musical instruments and passionate dance around ladders and shovels, flamboyant garments and elaborate knitted caps (the kind Flagstaff hippies would kill for), a swarming mass, teetering at the brink of lunacy. Moving determinedly across the cobblestones and into the ancient church—ladders with which to lower, shovels with which to inter—the crowd approached. He, still in the prime of youth, wept, knowing there was more to come.

*

My father found the Christ in an antiquities shop in the vicinity of El Rastro, Madrid’s flea market. There were other acquisitions that year, joining us at 77 Francisco Silvela before our departure for Iowa. Among them, an early Spanish panel painting of Christ at the Column—as a kid, the fascination was the sixth digit on his left hand—the African harp, and a fifteenth century Madonna and Child, missing her crown. The

My father found the Christ in an antiquities shop in the vicinity of El Rastro, Madrid’s flea market. There were other acquisitions that year, joining us at 77 Francisco Silvela before our departure for Iowa. Among them, an early Spanish panel painting of Christ at the Column—as a kid, the fascination was the sixth digit on his left hand—the African harp, and a fifteenth century Madonna and Child, missing her crown. The  wooden statue was so covered with grime, our Faustina declared she’d never seen a Madonna tan cubierta de mierda, so covered in shit. Pa spent several days cleaning her.

wooden statue was so covered with grime, our Faustina declared she’d never seen a Madonna tan cubierta de mierda, so covered in shit. Pa spent several days cleaning her.

I don’t remember where everything came from, but there were trips out of Madrid to Avila, Toledo, and Segovia, with visits to museums, sites, and dealers.

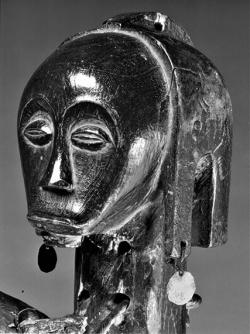

Many things caught my father’s eye, but he was stopped in his tracks by the harp. Though he still hadn’t begun to own, he was aware of African art. One of his first print students had been Roy Sieber.

Roy and his wife, Sophie, rented the upstairs of our house on Summit Street in those early years, and our families became lifelong friends. Sieber went on to receive the first PhD in African art history from the University of Iowa, made trips to Africa and ultimately became a foremost authority in the field. In addition to this close relationship with Sieber—the eager exchange of knowledge and visual experiences would stretch far into the future—my father knew of many artists’ fascination with non-western art, including Matisse, Lipchitz and Picasso. They had been discovering tribal art since the first decade of the century, so it seems reasonable that Pa would have seen photographs of their sculptures.

Facts of attribution were secondary for him. He was an artist, not a scholar; he would leave that to his friend, Sieber. The harp’s tribe was the Fang people of Northern Gabon, and its purpose of creation? An instrument of communication with the spirit world of Fang ancestors. When my father first encountered the harp, it’s unlikely he knew any of these details, or that it would prove to be extraordinarily valuable, or that it would become iconic in the world of Fang art.

But Pa knew aesthetic uniqueness, and he instinctively recognized what he needed: the maker’s emotive candor, his humility, his humanity. With future purchases of primitive art, this winning combination could make my father tune-out the world, and make him ‘want’.

My siblings recall a purchase price of fifteen dollars. Amazing now, but it couldn’t have been trivial in 1953, especially for an American university professor with a wife and four children, and his Guggenheim Fellowship’s fixed amount. The harp, my parents’ first primitive piece, became the nucleus of their collection. The assemblage of art eventually stretched beyond paintings by graduate students, my father’s own work, Pre-Columbian sculpture, Japanese, Piranesi, and Goya prints, to concentrate solely on the numerous tribes of Africa. The years changed my father’s collecting habits and purpose. What began as a young man’s diversion grew into passion, passion that morphed into need, need that became the mania of possession accompanying him to the end of his life.

I never questioned that the Christ belonged with us, that he would fare better in Iowa than collecting dust in the backroom of an antiquities shop. After lengthy negotiations and arrangements, he was crated and shipped to Iowa directly from the dealer’s establishment. My older brother, William, was included in the covert preparations and hushed talk. I blithely carried on with my activities, oblivious to what was going on, including possible complications. The exportation of historic art from Franco’s Spain was no small matter.

A separate crate, containing the Madonna and Child and a few other pieces, was packed with articles of clothing, household effects and my brother’s black bomber jacket. This was probably done on the chance our container would be pried open and inspected by Spanish customs officials. While unaware of the details regarding our Christ’s departure for the new world, when those wooden boxes were dismantled in our Iowa living room, I was not at all surprised to see William’s jacket.

404 South Summit in Iowa City had to have been more peaceful than our Christ’s beginning, possibly in that church with the leaky roof. I was familiar with Spanish women in black, their cloth slippers shuffling across cold stones of churches and cathedrals. Approaching in prayer, they must have pleaded for so many things, so many cures, so many miracles he could not fulfill. In our home, there were no expectations. We felt his relief, his serenity.

Countless came to see our Romanesque friend: those who could see and those who couldn’t, the knowledgeable and those who weren’t, the art faculty, students, curious neighborhood kids, and finally, our caring, family doctor, Pauline Moore, a devout Catholic. She’d stop by our home whenever one of us was sick. It was a bonus that Christ was present. In response to my mother’s calls—a fever, possible strep throat, flu, general malaise—she’d show up at the end of the day on her way home. It was the ‘polio scare’ era: public swimming pools and young, stiff necks that would not bend to touch chests. Tired and hoarse after long hours of work, our patient doctor would amble into the living room to write out prescriptions. Sinking into one of the Eames’ style plywood chairs, she’d kick off her shoes and settle back for a few minutes of quiet reflection in the company of our ancient friend. I was fascinated by her empathy, her acquiescence. More than once we saw her leave our house moist-eyed and remarkably refreshed.

Our parents’ protective, evasive natures prolonged our innocence and ignorance. Barely conscious of world religions, I knew little of the traditions we came from, what would have been our birthrights. Yet when we were kids, sharing the living room with our Christ from Burgos, possibly there was no need for religious knowledge. For us, he was not about belief, as he was for our family doctor. He was another work of art, another opportunity to exercise our visual curiosity and appreciation. If Pa had spoken about birthright, if he’d used the word—which I never heard him do—I believe he would have considered art to be our heritage, our inheritance. Did any of us give thought to how completely we were raised in its embrace, how comfortably and easily we moved in the visual world? I certainly took it for granted.

When my father presented us with art he admired, it had already been filtered through his lenses, yet he refrained from intruding when it came to our individual pursuits and interests. True in my case, but I became a writer, not an artist. My artist-siblings might have different thoughts on the subject. As with most parents and children, my dad and I had shared experiences—the same landscapes, the same familial and societal concerns, the same positive and negative poles, waiting for our winds to point us during dilemmas and under duress. Sometimes he spoke about our joint encounters, other times he did not. He moved quickly. There was always more beyond, more to see, more to accomplish. He didn’t dwell, especially if he felt the experience irrelevant to him—a trait I’ve come to identify as ‘male’. Women are more willing, timewise and emotionally.

Pa wasn’t concerned with my imaginative explorations. My inclination to literature and writing presented him neither vested interest nor threat. This reality was—knowingly or unknowingly—a wand’s wave of genius on his part, a stroke of luck for me.

At the time my parents moved from Summit Street, they gifted the Christ to the Cedar Rapids Museum of Art, where it was displayed for many years. When I wanted an image, and before my brother, Phillip, located the one included in this writing, five photos arrived by email from the director. The close-ups were taken in the museum basement—individual shots of the head, torso and thighs lying on a white sheet—looking, for all the world, like something from a post-mortem, rather than a museum’s storeroom. Missing were the tagged toes. What a way to end.