How did your parents meet? I remember when my friends in grade school compared notes about the first romantic meetings of their moms and dads—my parents went out in high school, mine met on a blind date, mine at the movie theater—and they’d turn to me with an extra charge of curiosity, a more purposeful focus: How about mine?

They didn’t say it but they were asking, How did my conservative Afghan father, with his thick accent, grumpy demeanor, and the inability to get along with the good Christian folks of our small town, end up with my pretty, blond, high-heeled, publicly pleasant Catholic-Slovak-American mother? To add to the mystery, my family had spells of involvement with foster care, family court, the local police, and the county jail. At the start of new school years, teachers raised their eyebrows skeptically when they saw my name on their student roster. Ah, another Nadir.

So how did the husband and wife at the helm of this notorious family get their start together? I honestly don’t know. My parents would never tell me. But I have theories, and I wrote about them in “Cold War,” my essay for the North American Review’s Summer 2013 issue.

Their entire relationship, at least what I experienced of it as their daughter, was an endless cycle of violent fights and tearful make up sessions.

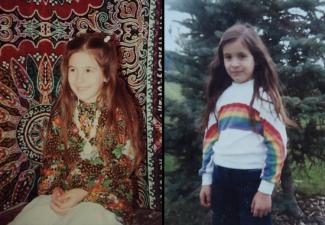

“Cold War” is an excerpt from the memoir I am writing, based in the 1980s, about the colorful marriage of my Afghan father and American mother, who together raised seven children, grew all their own vegetables, and sponsored the migration of dozens of Afghan refugee families into the United States. Yet, despite these collaborations, my parents never got along: Their entire relationship, at least what I experienced of it as their daughter, was an endless cycle of violent fights and tearful make up sessions.

I began work on my memoir after finishing my PhD in literature and theory at Columbia University. After being immersed in academic prose for nearly a decade, I assembled what imaginative resources I could find in my limited repertoire to assist me with my shift toward creative writing. One of my dissertation chapters had been on Willa Cather, and I found myself returning to a popular anecdote about how she came to write so successfully, an anecdote that contained writing advice that I now realize is a well-known creative writing precept. Cather’s first novel about high-society Boston failed miserably; only after her mentor Sarah Orne Jewett enjoined her to “write what you know” did she embark on the novels about her home state of Nebraska that brought her prominence. This little tale worried me. My memoir was about my Afghan-American childhood—an experience I obviously “knew” intimately—but it would also need to explain my parents, two people whom I described recently in an interview for Asian American Literary Review as “the most eccentric characters” I’ve ever known. And the originary event that made their relationship, and my childhood, possible—how did Mom and Baba meet?—was inaccessible to me.

In “Cold War,” I write, “Because they were engaged in a perpetual power struggle, my parents refused to tell me how exactly they met. They didn’t want to give each other that much credit. Their relationship had turned so bitter they couldn’t concede that, once, long ago, they had actually fallen in love.” How could I write a childhood memoir in which my parents figure so largely when I could not even figure out how they met? Was it possible to write a work of nonfiction involving two people so uncooperative that they wouldn’t answer me when I asked them basic questions about their life together?

...these narrative fragments were perhaps more telling than any tidy report my parents could have handed down to me.

I tried writing fiction instead (albeit autobiographical fiction) to fill the factual gaps. But this approach didn’t feel right for my material. Inserting details into a fictional version of my parents’ early relationship, even details likely to be true, made my story feel propped up. Such a coherent narrative was true to my experience neither as their daughter nor as their chronicler, and I didn’t want to take on the point of view of an all-knowing narrator when I’ve been in the dark for so long. The exercise was illuminating: Forcing a linear path to take form despite ubiquitous obstacles made me realize that my parents’ non-forthcoming-ness (and their mutual sabotage of their story) was integral to my memoir, and I needed to acknowledge that.

As my comfort with my mother’s and father’s silences and ambushes grew, so did my realization that there were emotional impulses circulating around what I didn’t know, cultural and historical details underlying comments I had heard, and these narrative fragments were perhaps more telling than any tidy report my parents could have handed down to me. I looked deeply at my parents’ avoidances, at their passive-aggressive jabs, at their casual references; I investigated and scoured my memory for clues. I did not write what I knew; I wrote in order to know. And this path led me through diverse, intertwined traces of their early romance, through pop feminism, USSR-US nuclear tensions, personal proclivities for the outdoors, dating practices (or lack thereof) in American and Afghan cultures, the Clarence Thomas Supreme Court hearings, and the US-funded Institute of Technology in Kabul.