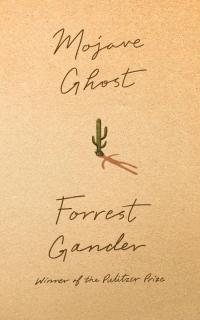

A Review of Mojave Ghost by Forest Gander

Much has been made of Forrest Gander’s college major, but what’s most remarkable is how it’s considered remarkable at all—a poet with a BS in Geology. Wouldn’t a good grounding in any kind of science seem to lend itself to the patient looking and thorough thinking such an exacting art demands?

In his latest collection, the resonantly titled Mojave Ghost, Gander—who grew up on the East Coast but was born on the West—returns to his roots in Barstow, California. Too small to call it a city but too big to call it a town, the poet’s birthplace sits along the western edge of one of the hottest deserts on the continent. It doesn’t take hopping off the busy I-15, halfway between LA and Las Vegas, to realize it’s a rocky, ragged, let’s say overtly geologic place, far in every sense from the desirable coastal locales for which the state is known.

Gander’s take, of course, is more cosmic than that. He may not mention the Pacific more than once in these pages, but a veritable ocean of desert, with its stretches of sand and burnt brown motley of rocks and scrub, makes aesthetic overtures the poet in Gander is helpless to ignore: he riffs on it and it riffs on him. And his college major comes in handy. Words of a type that Cormac McCarthy might have taken a shine to (and which his novels tended to suffer from) here serve to render one just-right image after another. Yet, more than just a virtuosity with the earth’s own specialized vocabulary, it’s Gander’s expert touch as an all-around wordsmith that enables him to impart his own idiosyncratic brand of experience—telegraphing what it’s like, say, to “lie listening to the ilmenite dark, / to the thrum of rain.” It’s wonderful how even his most alien lines seem to confer an intuitive understanding without necessitating recourse to the dictionary. Not just anyone will be able to rattle off the definitions for “arnica,” “laterite,” “spalling,” or “nidorous.” But in Gander’s hands, context tends to conspire with one’s gut instinct, and an elemental understanding is never far off.

Gander’s take, of course, is more cosmic than that. He may not mention the Pacific more than once in these pages, but a veritable ocean of desert, with its stretches of sand and burnt brown motley of rocks and scrub, makes aesthetic overtures the poet in Gander is helpless to ignore: he riffs on it and it riffs on him. And his college major comes in handy. Words of a type that Cormac McCarthy might have taken a shine to (and which his novels tended to suffer from) here serve to render one just-right image after another. Yet, more than just a virtuosity with the earth’s own specialized vocabulary, it’s Gander’s expert touch as an all-around wordsmith that enables him to impart his own idiosyncratic brand of experience—telegraphing what it’s like, say, to “lie listening to the ilmenite dark, / to the thrum of rain.” It’s wonderful how even his most alien lines seem to confer an intuitive understanding without necessitating recourse to the dictionary. Not just anyone will be able to rattle off the definitions for “arnica,” “laterite,” “spalling,” or “nidorous.” But in Gander’s hands, context tends to conspire with one’s gut instinct, and an elemental understanding is never far off.

Alongside these clarifications of the natural environment (including a whole lot of noticing what’s up with the animals, the birds especially, who call it home) runs a thread of love poetry which, at its most lyrically devotional, rivals the best of Rumi. In 2018’s Be With, Gander was a widower grieving the death of his wife, the poet C. D. Wright. He won a Pulitzer for that effort—cold comfort, maybe—but in Mojave Ghost there’s a rousing call for forward motion, for shedding past lives and slithering out from under them. “There is nothing in me now,” he writes, “of what I was before.” It isn’t always easy going, either; past and present jostle one another in competition for his attention—and no wonder: time goes taffy-soft beneath the desert sun.

What to say of the pastel

chromaticism of these Mojave sunsets?

Here, as everywhere, when you go still,

what has disappeared comes forward.

In the course of such a generous collection, one not just brimming but haunted with life, it’s fitting that the most marvelous poems are those responsible for sounding the emotional depths of Gander’s love life. Yes, he’s fallen in love anew, and his partner is everywhere in this book. The way she tugs at the corners of his poems, infusing them with her presence—sometimes literally, in casual quotation, lending an italicized ballast to Gander’s drift—will make you wish more poets would go out and find their muses. Gander calls what they have “the long encounter.”

Glancing up from the page to acknowledge

no one there. Which is only

one of your forms....

I recall the human event

of you turning your face

toward me for the first time. How

many lives before I fail to see it so clearly?

As tangible as they come, these are poems that periscope into moments. Not only do they call attention to the art of paying attention; they play host to an understated mysticism that binds to everything it touches, invoking what sometimes seems to be an accidental ethic of generosity. Such is love. When Gander opens his ear to the world, as poets do, the simple act of listening doubles as an invitation. “Meanwhile,” he writes, “do you hear it? That / insistent knocking outside the house?”

Which is when the brachiomandibular muscles contract,

forcing the hyoid bones forward in their sheath

so that the Gila woodpecker’s long tongue—

forked at the base of its throat, coiled

around its skull, and anchored to the eye socket—

is propelled through the drill hole

into a gallery of beetles

below the barky skin of a rotting saguaro.

There are no titles to be found in this book. Instead, marked off from one another by a twinkling of asterisks, the poems simply step forward one by one, saying what they need to say before clearing the floor for the next nameless piece. Their anonymity is part and parcel with Gander’s obvious striving for humility, which lends the book a refreshing “coming of age” quality. It makes an immediate kind of sense, then, to discover that Mojave Ghost is subtitled “A Novel Poem.” Rather than some 2D, paper-thin pose—playing with the categories of art for the sake of mess-making—the title invites direct comparison with another great poem, Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin (that “Novel in Verse”), the parallels of which emerge at the slightest glance: both about men struggling to achieve self-definition, both about a woman invested with the quality of completing the man. Rejected, unrequited—in Pushkin’s case—Onegin’s end is tragic. In contrast, Gander’s personal denouement—a wick he keeps trimming and lighting, trimming and lighting—might just make Mojave Ghost this season’s least expected comedy: not ha-ha funny, but a work with its own special kind of happy ending, the kind that exists in the wild but which nature likes to conceal—the same thing lovebirds feel when they’ve discovered their love does go on (as when the eye sees the world for what it is and the soul gladdens with wonder).

Perfectly adequate as a series of meditations on the meaning of “home,” an elaboration of the American Southwest from a poet with the vision to see a world in each of its grains of sand, Mojave Ghost is that rare thing—a book of poems with something new to say about love.

Recommended

A Review of Portable City by Karen Kovacik

A Review of Haircuts for the Dead by William Walsh

A Review of Birdbrains: A Lyrical Guide to the Washington State Birds