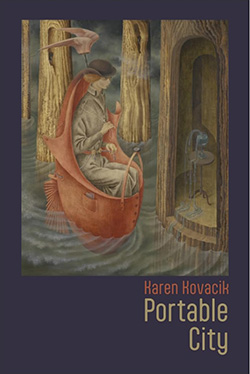

A Review of Portable City by Karen Kovacik

Karen Kovacik’s third collection of poems Portable City, published in 2025 by Hanging Loose Press, uses the title and opening poem as an introduction to the book in much the way same way that Elizabeth Bishop’s North & South uses an opening poem as a guide. Bishop’s influence is felt throughout Portable City, but especially in the title poem, an ekphrastic poem after the artist Yin Xiuzhen’s Portable Cities. In a 2017 Artspace interview, Xiuzhen explains the work and its significance:

In this series, I collected clothing worn by people in the cities I visited, and used these clothes to make small buildings that were then sewn into suitcases … The suitcase is a concentrated home for life on the road, and it’s an object that’s inextricably intertwined with globalization.

Xiuzhen’s series recalls the work of Joseph Cornell, an artist whose shadow boxes were a source of inspiration for Bishop, who wrote and published a translation of a poem by the Mexican poet Octavio Paz, “Objects and Apparitions,” which was dedicated to Cornell. It seems fitting then that Kovacik, a translator herself, would open with an ekphrastic poem that recalls Bishop translating Paz writing about and for Cornell, especially an ekphrastic poem that deals with the subject of travel:

You never know what

will fly out of my suitcase.

It has its own airport,

planes, and terrorists.

It bulges like a B-movie bomb.

Each of the four sections of Portable City creates a distinct silhouette in the collection’s skyline, which is wide and varied in scope.

That scope is highlighted in “Ghazal for the History of English,” which employs the ghazal form to narrate the history of the English language. In the notes, Kovacik explains how English has historically been “a tool of subjugation, but also a means of resistance,” an idea that is brilliantly illustrated through the ghazal, a form that allows for and even invites the transformation of the repeating word or phrase across couplets:

2001

In pace requiescat. Amen. Shantih shantih shantih.

Heed the fates of Latin and Sanskrit, O my brash English.

2004

This language is a murderer disguised as Mickey Mouse.

iPods and Google—two more Trojan horses of English.

By utilizing a form that was adopted into English, Kovacik cleverly demonstrates how English has become “the bastard of them all,” oscillating between exclusion and inclusion throughout history.

Kovacik’s work as a translator of Polish poetry is evident in this collection, with poems such as “Rothko in Warsaw,” “The Best Five Places for Kissing in Warsaw,” “Polski,” and “For Zbigniew Herbert” populating its pages. In addition to English, the poems in this book consider the Polish language and language in general, as the speaker muses on “the mysteries of verb and noun” and the “cold swan of language” that is her ancestral tongue. “It’s too late for me to unlearn Polish,” the speaker says in “Pandora Speaks,” as learning the language has changed her perspective of the world and altered her in a fundamental way.

Traveling from Poland to Mexico, poems such as “Globos del deseo,” “Ofrendas,” and “Ode to the Milagro Heart” make the collection a “Portable City” unto itself. In “Globos del deseo,” Kovacik alludes to Bishop’s “The Armadillo,” which describes the launch of “frail, illegal fire balloons” on St. John’s Day in Brazil. In Kovacik’s poem, the speaker observes a similar scene playing out on a beach in Puerto Vallarta:

Guys run with these balloons

to catch a breeze. Some globos

sputter on the sand, others flip

on their ascent, flare brief

as a wish, then plummet

to the sea …

Here, it’s not only the subject matter but also the quality of the observation and the musicality of the language that align Kovacik with Bishop; like Bishop’s, Kovacik’s speakers look closely at the world and translate their observations through language so rich and vivid it seems tactile.

In the second half of the collection, Kovacik turns her attention to the “Portable City” of the body and the “funk of late life” that includes aging and death. Many of the poems in the third and fourth sections are elegies, such as “Elegy for My Sex Life,” in which the speaker bids farewell to “stickiness and soapslide, all that gliding and lingering.” Similarly, in “Death and Turbotax,” the speaker tempers her mourning with a dose of humor, lightening the tone by framing her grief within the context of that most dreaded of tasks, filing one’s income taxes:

Black and white and blue

this mandate to recall the year—

your last. I’ve never run a fishery,

won big at blackjack or roulette,

but I contemplate each software prompt

as if examining my soul.

No, I’ve no electric vehicle,

yes, my husband died

before I finished this return.

Here again, the speaker of this poem recalls the speaker of Bishop’s “One Art,” who, while practicing “the art of losing,” must force herself to face and name her loss. In the same way, Kovacik’s speaker struggles to put her grief in perspective: “yet all this figuring on Schedule A / both makes you more remote and brings you close.” For both speakers, loss is made bearable when it is made visible: “like light, like printer ink, like you.”

For both poets, loss is also made bearable through travel and movement—both literal and figurative—an idea explored in “Treadmill with Virtual Active: Swiss Alps,” in which the speaker runs up a virtual Matterhorn, “fending off grief.” Acknowledging her position, the speaker declares that “Mine’s a different Matterhorn— / slog through life’s long middle,” as she describes herself as “a body in motion / and time,” who, having “outlived / the Romantics anyhow,” must now “walk and walk and walk / to get back down.” In “Polski” from the book’s first section, the speaker describes how “over decades I built on-ramps, / motorways, cities of concrete,” conflating language with place, as Polish becomes not only the speaker’s ancestral tongue but also a place she transforms as she inhabits and navigates it.

In Portable City, Kovacik offers an affecting and unsentimental examination of place, culture, language, and loss. “You don’t have a home until you leave it and then, when you have left it, you never can go back,” says James Baldwin. It is trying to get back home—back to the root of language, grief, and memory—that is the central project of this collection. For Kovacik, home is not a place to leave and lose but a journey that is continually created and recreated through language: “Let every sentence / be a life sentence / as it wends toward the grave.”

Recommended

A Review of Haircuts for the Dead by William Walsh

A Review of Birdbrains: A Lyrical Guide to the Washington State Birds

A Review of When We Were Gun: A Narrative Poetry Cycle by Deborah Schupack