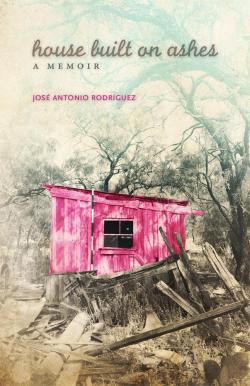

“Why then ’tis none to you; for there is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.” So exclaims Hamlet to his college buddies about their experiences of Denmark that are starkly at variance with Hamlet’s. Hamlet finds Denmark to be a prison; his fortune-favored or pampered friends “think not so.” We see much of this sort of consideration of the relationship between thought and experience over the course of the childhood of José Antonio Rodríguez, author of the melancholic memoir, House Built on Ashes, which I have been living with since its publication in 2017. Rodríguez, like the author of Hamlet, shows both the limits and the essential truth of the idea that one’s thought controls one’s emotional and mental states of being.

Rodriguez’s memoir can feel grimy to imagine and embarrassing to own, even imaginatively and only momentarily.

“The dark kitchen calls her back. She says nothing, which is everything. I close my eyes, the room hot and humid. In my chest, right beneath that bone in the middle, a little feeling of hardness settles like a small stone.” So closes “like a boy,” one of the longer vignettes of the memoir. This section recounts the memoirist’s experience of having two friends innocently humiliate him in front of their teacher and of wanting to do what is right and loving, even when the expectations, demands, and desires of one’s mother and one’s teacher are mutually exclusive. In the vignette, operating as most of them do thematically more than narratively, which is why they seem more like vignettes than chapters, the nine-year-old José is in a classroom with his two friends, Mario and Beto, and his teacher, Mrs. Jackson. Mario asks José, in front of Mrs. Jackson and really to put her on the spot, “Why do you carry your books that way? . . . Like a girl.” Beto agrees by exclaiming, “Oh, yeah, Miss, they’re always calling him names.” Mrs. Jackson “looks at them, then at [José], like she doesn’t know what’s going on, like if she looks at [José] long enough she’ll figure something out.” She doesn’t figure anything out. The friends eventually depart the room and Mrs. Jackson starts fresh, as if nothing, certainly nothing that puts a young queer, as I call us, into a traumatic state, what the actor Wentworth Miller calls “survival mode.” Mrs. Jackson asks why José is “all dressed up,” and José tells her that it’s “photo day.” He is wearing a button-down shirt and a crew neck undershirt, the latter because his mother insists that it’s necessary and proper. Mrs. Jackson says that the undershirt “shouldn’t show” and then gets him to take it off. Later at home, José’s mother asks him why he isn’t wearing his undershirt. He tells her “what happened, that the teacher thought it shouldn’t show.” His mother says nothing but is plainly upset, but exactly at what José doesn’t say, because he cannot quite know, and because his mother doesn’t quite know. It’s good to be saved from a faux-pas, but it’s good—better?—to have a mother’s wishes respected. And what is there to do about any of it at this point? Reprimand plainly distraught José? Complain to Mrs. Jackson? It’s a school photo. Important, yet not so. These are some of the possible suggestions for José’s mother’s feelings as she “purses her lips, drops her apron over her lap, and her hands smooth it out slowly, like she’s not sure what comes next.” They are also emotions José feels in some way, compounded by the trauma, unknown to his mother, of being put in homophobic survival mode for the entire undershirt incident. There is nothing for José to do but to suffer. And it’s no one’s fault, even as many people contribute.

“The dark kitchen calls her back. She says nothing, which is everything. I close my eyes, the room hot and humid. In my chest, right beneath that bone in the middle, a little feeling of hardness settles like a small stone.” So closes “like a boy,” one of the longer vignettes of the memoir. This section recounts the memoirist’s experience of having two friends innocently humiliate him in front of their teacher and of wanting to do what is right and loving, even when the expectations, demands, and desires of one’s mother and one’s teacher are mutually exclusive. In the vignette, operating as most of them do thematically more than narratively, which is why they seem more like vignettes than chapters, the nine-year-old José is in a classroom with his two friends, Mario and Beto, and his teacher, Mrs. Jackson. Mario asks José, in front of Mrs. Jackson and really to put her on the spot, “Why do you carry your books that way? . . . Like a girl.” Beto agrees by exclaiming, “Oh, yeah, Miss, they’re always calling him names.” Mrs. Jackson “looks at them, then at [José], like she doesn’t know what’s going on, like if she looks at [José] long enough she’ll figure something out.” She doesn’t figure anything out. The friends eventually depart the room and Mrs. Jackson starts fresh, as if nothing, certainly nothing that puts a young queer, as I call us, into a traumatic state, what the actor Wentworth Miller calls “survival mode.” Mrs. Jackson asks why José is “all dressed up,” and José tells her that it’s “photo day.” He is wearing a button-down shirt and a crew neck undershirt, the latter because his mother insists that it’s necessary and proper. Mrs. Jackson says that the undershirt “shouldn’t show” and then gets him to take it off. Later at home, José’s mother asks him why he isn’t wearing his undershirt. He tells her “what happened, that the teacher thought it shouldn’t show.” His mother says nothing but is plainly upset, but exactly at what José doesn’t say, because he cannot quite know, and because his mother doesn’t quite know. It’s good to be saved from a faux-pas, but it’s good—better?—to have a mother’s wishes respected. And what is there to do about any of it at this point? Reprimand plainly distraught José? Complain to Mrs. Jackson? It’s a school photo. Important, yet not so. These are some of the possible suggestions for José’s mother’s feelings as she “purses her lips, drops her apron over her lap, and her hands smooth it out slowly, like she’s not sure what comes next.” They are also emotions José feels in some way, compounded by the trauma, unknown to his mother, of being put in homophobic survival mode for the entire undershirt incident. There is nothing for José to do but to suffer. And it’s no one’s fault, even as many people contribute.

How before I could wave hi to Joe

my sister called him a faggot

because of the way he walked

hips swishing, head bobbing.

How she didn’t say it to him

but whispered it to me. How

at that moment

the late afternoon sky suddenly dimmed,

just a little. How only I noticed.

These verse sentences come from “Joe, I never write about you” included in José Antonio Rodríguez’s 2011 book of poems, The Shallow End of Sleep. The prose-leaning verse seems of a piece with the poetic-prose of the subsequent memoir. The numbing anaphora of “How,” with all of the detail it introduces throughout the poem, produces the sort of heavy yet entirely indeterminate melancholy that escapes acuteness only because it’s all recurringly, yet unpredictably, ephemeral. While unpredictable, once passing, the melancholic quality—mild sadness, wistfulness, wishing things might have been otherwise even as the way they were makes us now, near joy—presses, the way the “late afternoon sky suddenly dimmed,” yet with the solitary “only I noticed.”

Rodriguez’s memoir can feel grimy to imagine and embarrassing to own, even imaginatively and only momentarily. The dirt, the urinary incontinence, the socio-political vulnerability, the abjectness all can frighten as they become, in these artful lines and pages, familiar. In this, as in the maturation registered toward the end of the story, it shares with The Confessions of St. Augustine the sense of moving from ignorance to comprehension of mystery, minus the confidence Augustine expresses in the goodness of existence. The latter part of Augustine’s 9th book, in which he comes to terms with his mother’s life and death and his own existence in his conceptual reality, provides the feeling of metonymical comprehension, affection, and acceptance that was to become an hallmark of the genre. Reporting his final discussion with his mother as she lay dying, Augustine, for instance, tells us that

We were saying then: If to any the tumult of the flesh were hushed, hushed the images of the earth, and waters, and air, hushed also the poles of heaven, yea the very soul be hushed to herself, and by not thinking on self surmount self, hushed all dreams and imaginary revelations, every tongue and sign, and whatsoever exists only in transition . . . so that life might be for ever like that one moment of understanding which now we sighed after; were not this, Enter into thy Master’s joy? And when shall that be? When we shall all rise again, though we shall not all be changed?

Rodríguez’s masterful vignette, “siren,” brings such confessional maturation into postmodern life-writing and life-reading. In two and half pages, and in his distinctively metonymical manner, a manner readers have been schooled well in by the time they reach this late set-piece, Rodríguez harmonizes math and sex, knowledge and love, thought and realities by coordinating these with his college library, experiences of sex and math, an adult bookstore, and the police. Each place, each experience, each bit of knowledge feels true and even, in a far less significant way than the modern English grammar of the linking verb promises, it is true, Rodríguez reveals, never more so than when its falsehood overwhelms it. As with each new, higher-level school’s bigger library and with each advancement in mathematics education, “[i]t’s the same with sex.” The “it” is the lie that each reveals in the certitude of the previous institution or iteration of fact, even as the lie is understood to be necessary in coming to comprehend the current, new, advanced, yet surely also as contingent and ephemeral, institution or truth. All culminates or comes together in the end with the flashing lights but silent siren of the police. Concluding his reverie about knowledge, math, and existence with,

So I figure, when all lines eventually intersect, when all that crossing creates a chaos no mathematician can decipher into order, when everything comes crashing into each other, is it like a black hole or a supernova? The end of a universe or the beginning? The day dawning or the day dying?

Rodríguez, approaching an adult bookstore, concludes the vignette with the following speculative observation:

The lights above the police car whirl without the siren, and it seems like a contradiction, a warning that isn’t fully uttered. I wonder if there are men in there doing the thing I dream of when I let myself dream of it, if that thing they do mends the heart or further breaks it.

Both and neither. Culpable and innocent. Warned and seduced. Almost exquisite suffering and almost exquisite knowingness the memoir provides as the abiding experience of this singular poet’s youth. I can’t manage to maintain the experience as long as I would like, but I’m always rewardingly edified when I am able to dwell in it for a while. It makes sense of much that I have found inexplicable about queer life in America.