I feel as though I should begin my review of The William H. Gass Reader with a disclaimer like those espoused by the anchor of the evening news when the forthcoming story is about the entity which owns the TV station for I have been a Gass subsidiary of sorts for more than a decade. Of course, no money ever exchanged hands, at least not in the direction of my hand. A few of my pennies would fall into Gass’s, I should hope, after being filtered through third, fourth and fifth parties in the form of booksellers, publishers and agents.

So there you have it up front: I have been a disciple of William H. Gass’s writing since my doctoral days at Illinois State University, where I wound up devoting much of my dissertation to Gass’s fiction. (1) That was only the beginning, however. Since then I’ve published a bit on Gass—a review of Middle C in NAR (298.4), for example—but most of my critical work has been in the form of conference papers, something like a dozen of them (all available at my own blog). A student a few years ago coined the phrase that I was “preaching the Gass-pel,” and I promptly purloined the expression because it is both amusing and true: Gass is my religion, and I speak of his Word with the fervor of a Witness who has just rung your bell.

So there you have it up front: I have been a disciple of William H. Gass’s writing since my doctoral days at Illinois State University, where I wound up devoting much of my dissertation to Gass’s fiction. (1) That was only the beginning, however. Since then I’ve published a bit on Gass—a review of Middle C in NAR (298.4), for example—but most of my critical work has been in the form of conference papers, something like a dozen of them (all available at my own blog). A student a few years ago coined the phrase that I was “preaching the Gass-pel,” and I promptly purloined the expression because it is both amusing and true: Gass is my religion, and I speak of his Word with the fervor of a Witness who has just rung your bell.

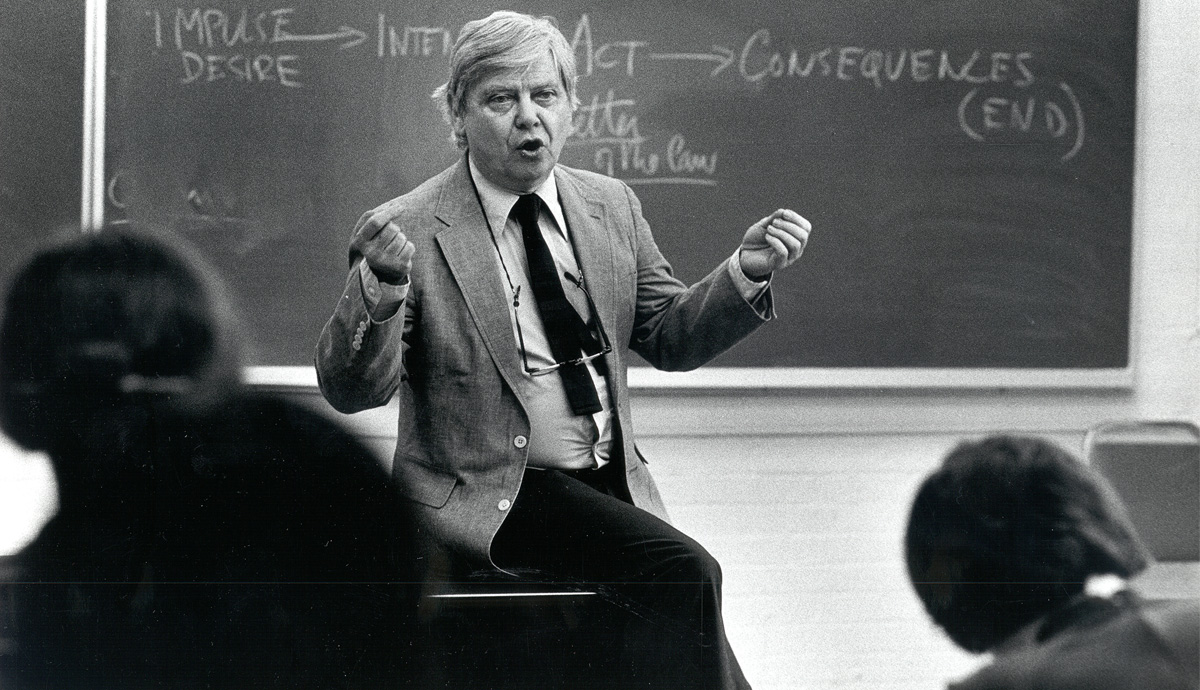

Moreover, Gass has been at the heart of (the heart of) my teaching and writing. He is a constant presence in my classrooms, both the earthly one and the ethereal one. Since 2016 I’ve been a lecturer in Lindenwood University’s MFA in Writing program online. To date, I haven’t taught a course devoted exclusively to Gass’s work, but in a sense there’s no need because every class I teach contains a regular dose, a steady I.V. drip, of his thoughts on writing. Besides his creative work, he wrote frequently about writing—he’s given credit, incidentally, for inventing the word metafiction—and he was a generous granter of interviews, during which the topic regularly turned to technique. (2)

Gass has been at the heart of (the heart of) my teaching and writing. He is a constant presence in my classrooms, both the earthly one and the ethereal one.

So regardless of the text, I offer my fine-artists-in-making insights from the Master. (You likely think of Henry James as “the Master,” as did Gass, but not so in my world.)

In addition to his fiction and his criticism, Gass was a sought-after reviewer of books. His reviews were known for their wit and wisdom, but equally so for their seeming only barely connected to the book or author under consideration. Thus, given that this review quickly veered away from the business at hand, know it is a meandering the Master would approve.

Nevertheless, some vital data are overdue. The William H. Gass Reader (Knopf, 2018) is a nearly 1,000-page collection of fiction and nonfiction that spans six decades, divided into four sections: Introduction, Fiction, Artists, and Theory. Gass earned a Ph.D. in philosophy from Cornell University (1954), where he briefly studied under Ludwig Wittgenstein, and he put bread on his table by teaching philosophy at the College of Wooster (1949-54), then Purdue University (1955-68), and finally Washington University in St. Louis (1968 to his retirement in 2000). For the final decade at Wash U Gass directed the International Writers Center, which was dedicated to nurturing writers around the world, and bringing a goodly number of them to St. Louis to read and teach master classes.

The Reader, which is coming out in paperback October 8, is unusual among such texts on a couple of counts. Collections known as readers are often published quite posthumously and their contents are selected (and frequently introduced) by an editor. Gass’s Reader was published posthumously, too, but only just (he died December 6, 2017); therefore, Gass selected the material himself, and worked with his editor at Knopf to determine the order. Moreover, Gass sowed notes throughout its pages in the form of bracketed commentary. (3)

Another typical characteristic of readers is that their author’s longer works tend to be represented by excerpts which carry conspicuously the scent of incompleteness. Not the case with The Gass Reader, at least not exactly. Much of its contents is given whole: the reviews and essays, two short stories, three novellas, and three translated poems. Gass’s three novels are represented—Omensetter’s Luck (1966), The Tunnel (1995), and Middle C (2013)—but even these are in the form of stand-alone pieces which appeared originally in journals and garnered prizes such as Pushcarts (four), Best American Stories (five), an O’Henry, and a Longview Foundation (judged by Saul Bellow).

Since Gass’s own hand selected and arranged his Reader’s contents, and since he understood his end couldn’t be far off (his ninetieth birthday celebration at Washington University, in 2014, was delayed by several weeks due to deteriorating health), he must have considered the collection a resounding mark of punctuation on a long literary life. If Gass thought of The Reader as a sort of final statement, I asked myself, what did he want it to say? It would be an insult to the Master and an embarrassment to me if I suggested that The Reader has a single thing to say, when in fact it has many—more than I know; more, even, than Gass knew. As he remarked of great works of literature, “There is no gist, no simple translation, no key concept which will unlock these works; actually, there is no lock, no door, no wall, no room, no house, no world. . .” (“On Reading to Oneself”).

Rather than a final statement, it is more accurate to think of The Reader as a last course, elaborate in its curricular construction, which is fitting since Gass dedicated his adult life to teaching and was highly regarded in the classroom and lecture hall. He won several honors in recognition of his teaching, among them the Sigma Delta Chi Best Teacher Award, and he was named by the Chicago Tribune One of the Ten Best Teachers in the Big Ten. Also, at his memorial celebration, on the Wash U campus, former students offered eulogies in praise of Gass’s generosity with his time, and they noted the impact he had on their lives, especially their writing lives.

What, then, is Gass the teacher teaching us in his Reader? Again, the lesson is multifaceted, but perhaps the main idea is captured in the opening piece, “Retrospection,” which Gass wrote at age 87 (he tells us) for inclusion in Life Sentences (2012), his final collection of essays. Citing Plato and Socrates, he states, “[T]he removal of bad belief [is] as important to a mind as a cancer’s excision [is] to the body it imperil[s]. To have a head full of nonsense is far worse than having a nose full of flu. . . .” Gass goes on to encourage rigorous self-skepticism regarding one’s own ideas, “theorizing” about errors in thinking: “Skepticism,” he writes, “was my rod, my staff, my exercise, and from fixes, my escape.”

This careful self-criticism must be undertaken via the careful reading of great books, and Gass follows his opening piece with “Fifty Literary Pillars: Texts Influential to My Literary Work,” a list with commentary of, actually, 51 books which contributed to his development as a writer. Numerous works of philosophy are included (Plato, Aristotle, Hobbes, Kant, Wittgenstein), as are several works of criticism (Bachelard, Coleridge, Valéry), and even diaries (Woolf), letters (Flaubert), sermons (Donne), and hymns (Hölderlin). However, the lion’s share of titles are creative works (Jonson, Shakespeare, Kafka, James, Pound, Yeats, Stein, Stevens, Porter, Faulkner, Gaddis, Hawkes). Most influential, which comes as no surprise to those who know Gass at all, was Rainer Maria Rilke’s oeuvre. Of Rilke’s Duino Elegies, Gass writes, “They gave me my innermost thoughts, and then they gave those thoughts an expression I could never have imagined possible for them.”

Gass identifies the problem (harried, distracted and uncritical minds), underscores the stakes (one’s soul, and even worse in America, one’s money), and presents the solution (the slow and serious engagement of great literature and art).

Following the list of 51 intellect-altering texts is Gass’s “On Reading to Oneself,” which was written as a commencement address for Washington University’s Class of 1979. Gass cautioned the grads: “We are expected to get on with our life, to pass over it so swiftly we needn’t notice its lack of quality, the mismatch of theory with thing, the gap between program and practice. . . . We’ve grown accustomed to the slum our consciousness has become.” The cure, he advised, is the reading of great books, “for reading is reasoning, figuring things out through thoughts, making arrangements out of arrangements until we’ve understood a text so fully it is nothing but feeling and pure response.” The slow but steady development of a critical intellect is imperative, and Gass dramatically drives home the reason why in the Introduction’s next piece, “Even if, by All the Oxen in the World”: “[P]opular culture is the product of an industrial machine which makes baubles to amuse the savages while missionaries steal their souls and merchants steal their money.” Gass wrote this sentence for a piece published originally in 1968, but it may as well have been written in 2018, when the need for a critically engaged citizenry may be even greater than it was during the Vietnam War era.

So, in the Introduction, Gass identifies the problem (harried, distracted and uncritical minds), underscores the stakes (one’s soul, and even worse in America, one’s money), and presents the solution (the slow and serious engagement of great literature and art). What follows is Gass’s fiction, his own offerings of literature to be read carefully and considered rigorously.

The Reader contains a generous selection of Gass’s creative works, nearly 300 pages’ worth, arranged in the order of their publication. As mentioned earlier, some may appear merely to be representative of his book-length works, but each has enough narrative autonomy that it was published as a stand-alone piece. In fact, several earned accolades for short fiction, including the opening title, “The Love and Sorrow of Henry Pimber,” from the novel Omensetter’s Luck, but first published in Accent and reprinted in The Best American Short Stories (1961).

The project that dominated Gass’s creative writing life for nearly three decades was the novel The Tunnel, which began to appear in 1969, in New American Review, and was finally published as a 650-page novel in 1995, for which he won the American Book Award. Over the years various parts of The Tunnel came out in a host of prestigious journals (among them TriQuarterly, Granta, Yale Review, Kenyon Review, and Esquire). The Reader includes several sections from Gass’s magnum opus, including two that he seemed to be especially fond of given the number of times he chose them for readings: “An Invocation to the Muse” and “A Fugue.” (4)

In spite of the critical success of his novels, Gass felt that the novella was his natural medium, and they are well represented in The Reader. He said that he preferred writing novellas—over short stories and novels—because they were long enough to allow for the development of themes and motifs and so on, but short enough that he could write one in a reasonably brief amount of time (compared, say, to the three decades it required to write The Tunnel). The Reader includes his first published novella, “The Pedersen Kid” (originally brought out by an editor and fellow writer who would become a valued friend, John Gardner), as well as “Emma Enters a Sentence of Elizabeth Bishop’s” (from Cartesian Sonata, a collection of novellas) and “In Camera” (from his final book of fiction, Eyes, a collection of novellas and stories).

Gass was known as one of the premier stylists of his generation. He had little interest in characterization and plot, but instead was chiefly concerned with creating works of linguistic art. He writes in “Retrospection,” “[T]he artist’s fundamental loyalty must be to form, and his energy employed in the activity of making. Every other diddly desire can find expression; every crackpot idea or local obsession, every bias and graciousness and mark of malice, may have an hour; but it must never be allowed to carry the day.” This fundamental loyalty no doubt kept Gass off of best-sellers lists, but it earned him a wealth of awards and the respect of serious readers and writers around the world (his fiction has been translated into French, Italian, German, Japanese, Dutch, Spanish, Rumanian, Hungarian, Polish, Hebrew, Czech, and Slovene). He was an obsessive and determined reviser of his prose. In the Gass archive at Washington University, the manuscript pages of rough drafts number in the thousands of pages, perhaps tens of thousands. Single paragraphs went through dozens of manually typed iterations before reaching their final form. In margins, Gass would scan sentences like lines of poetry to get the rhythm, the feel and the sound just right. (5)

While Gass was not known as a poet per se, he was a prose writer who used language poetically. Here, as illustration, is a passage from “Emma Enters a Sentence of Elizabeth Bishop’s”:

Emma’s eye would light; it would linger; it would leave. Life too, she was avoiding. There were days she knew the truth and was oppressed by her knowledge. These were days of discouragement, during which, almost as a penance, she would sew odd objects she had carefully collected to squares of china-white cardboard, and then inscribe in a calligrapher’s hand a saying or motto, a bit of buck-up or advice about life, which seemed to express the message inherent in her arrangement of button or bead or bright glass with star shape of glued seeds, dry grass, or pressed petal, then, sometimes, hung from a thin chain or lace of leather, a very small brass key, with colored rice to resemble a fall tree, and a length of red silk thread like something slit.

We note the alliteration, repetition, internal rhyme, and vivid imagery. In an interview in 1984, Gass said that the day’s finest working poets were in fact novelists, like Hawkes, Gaddis and Coover. It would have been bad form to include himself in the list, but these were writers among whose names Gass’s was often included; and we find evidence of his poetic prose style throughout The Reader.

Included from In the Heart of the Heart of the Country is the collection’s title story, for which I have a special affection and affinity. It was the first thing I read by William Gass. Though originally published in 1967, I didn’t encounter it (or knowledge of him) until 2009, when I bought a used copy of Norton’s Postmodern American Fiction anthology as a part of my doctoral hording in the run up to writing my dissertation. I had intended to focus on Gaddis and Pynchon, but when I read “In the Heart of the Heart of the Country,” I fell in love. As Cupid would have it, a couple of weeks later I was at the AWP Conference in Chicago, where there was a tribute panel devoted to Gass. After enduring a tiresome trio of long-winded introductions, Gass was finally allowed to read from his work. I don’t recall the entire program that he shared with the seeming few of us who were gathered in the opulent (perhaps ostentatious) ballroom, capacious enough to easily fit hundreds beneath its elaborate chandeliers, but I do remember that it had an insect motif and began with his early story “Order of Insects” (1961), which he identified more than once as his best piece of writing (included, not surprisingly, in The Reader).

Thereafter, I began reading Gass ravenously, and found that his oeuvre fit into my dissertation topic more effectively than Gaddis’s or Pynchon’s—writers I admired, but for whom a passion had never ignited. This wasn’t the case with the Master. The more I read, the deeper I fell and the more devoted I became. In 2011, I found myself living alone—just my dog and I—for the first time in more than a quarter century. I had finally extricated myself from a woeful marriage, and the kids were away at college or making their way in the world. There was something about “In the Heart of the Heart of the Country”—an oddly arranged first-person story about an aging poet living alone in a typical Midwestern town—that spoke to me as nothing else did:

I feel, on my perch, that I’ve lost my years. It’s as though I were living at last in my eyes, as I have always dreamed of doing, and I think then I know why I’ve come here: to see, and so to go out against new things—oh god how easily—like air in a breeze. It’s true there are moments—foolish moments, ecstasy on a tree stump—when I’m all but gone, scattered I like to think like seed, for I’m the sort now in the fool’s position of having love left over which I’d like to lose; what good is it now to me, candy ungiven after Halloween?

There was a peacefulness in my solitude, a sort of exquisite and long-desired loneliness. It was a time to rethink and reset, a contemplative intermission before embarking on the second act of my life. “In the Heart of the Heart of the Country,” even more so than other Gass, became like (or strike like) a religious text on which I meditated almost daily. It comforted, it inspired, and it encouraged me to soak in this solitary state, which turned out to be short-lived as it was only eight or nine months before my life began to be repopulated—yet the story remains special to me as a sort of anthem that speaks to the nobleness of ending, but then beginning again. Says Gass’s poet, “I must organize myself. I must, as they say, pull myself together, dump this cat [dog actually] from my lap, stir—yes, resolve, move, do. . . .”

Gass concludes, “The question is whether it is better to die of a good life or from a bad one. If we fail (and I wouldn’t bet on our success), there will be one satisfaction: we shall probably be eaten by our own greed, and live on only in our ruins, middens, and the fossil record.”

After The Reader’s tour of Gass’s fiction, the final course continues with the Artists section, seventeen essays in which the Master discusses some of his most-admired writers, offering insights on how their work could be approached. Here we have Rilke, of course, and Valéry, as well as Rabelais, Kafka, Lowery, Borges, Pound and James (the other “Master”). There is Katherine Anne Porter, Colette and (perhaps most notably) Gertrude Stein, about whose Three Lives Gass writes, “I knew I had found the woman my work would marry” (“Fifty Literary Pillars”). Specifically, in this section Gass has included “Gertrude Stein and the Geography of the Sentence” (1973), a nearly 50-page analysis of Stein’s unique style, rich with examples and diagrams: “Almost at once she realized that language itself is a complete analogue of experience because it, too, is made of a large but finite number of relatively fixed terms which are then allowed to occur in a limited number of clearly specified relations. . . .”

The final two essays in Artists may seem like odd-men-out, as they don’t focus (much) on specific writers. The section’s penultimate essay, “On Evil: The Ragged Core of a Sweet Apple” (2004), is a lengthy meditation on various manifestations of evil in the Judaic/Christian literary tradition. Gass concludes, “The question is whether it is better to die of a good life or from a bad one. If we fail (and I wouldn’t bet on our success), there will be one satisfaction: we shall probably be eaten by our own greed, and live on only in our ruins, middens, and the fossil record.” The final essay of the section continues the theme of evil unleashed, “Kinds of Killing: The Flourishing Evil of the Third Reich” (2009), ostensibly a review of Richard J. Evans’s The Third Reich at War in which Gass covers in detail the rise of the Third Reich after Germany’s defeat in the First World War, examining in particular the Nazis’ actions and atrocities. Evans’s book begins with the annexation of Poland, and therefore so does Gass’s critique. He writes, “[The Poles] should be confined to the muddles they made and their ignorance encouraged. Germany’s earnest efforts to rub out any influence Polish intellectuals might have on their society, by removing them from their own lives, seem odd when dealing with such a presumably dumb bunch.” In their placement, the section’s closing essays remind us of the dangers discussed in The Reader’s Introduction if we fail to read the kind of writers who Gass examines in the section’s first fifteen pieces.

We have now come roughly two-thirds of the way through The Reader (through the Master’s master course). We have been shown how reading impacted Gass’s intellectual development and how it can influence ours as well. He has demonstrated his virtuosity, inviting us to exercise our own intellect. He then recommended a host of writers about whom we should be interested, and he suggested useful ways of entering their masterworks. Now he’s reminded us just how much evil lurks in humanity’s heart and just how close to its onion-skin skin, suggesting that an appreciation of art and literature may be the only way to stay evil’s seepage into the world—if it can be stayed at all.

The final third of The Reader is devoted to Theory, and may be seen as a guide to writing one’s own literature, not so much a practical guide, but rather a theoretical one, a philosophical one. Among the fifteen pieces are “The Concept of Character in Fiction,” “The Music of Prose,” “The Book as a Container of Consciousness” and “The Architecture of the Sentence.” In these essays some of Gass’s more esoteric ideas about writing fiction are elaborated, for instance his concept of character: “[T]here are some points in a narrative which remain relatively fixed; we may depart from them, but soon we return, as music returns to its theme. Characters are those primary substances to which everything else is attached. . . . anything, indeed, which serves as a fixed point, like a stone in a stream or that soap in Bloom’s pocket, functions as a character.” It is these essays on narrative theory, along with Gass’s creative work, which have had the most profound influence on my own writing—and they have provided significant fodder for my teaching, especially in my discussions with MFA students who are molding themselves as writers of narrative. A well-wrought course should conclude, ideally, with the students on a trajectory to eventually surpass the mastery of their master. The Theory essays can be read as Gass’s final instructions before graduating readers into the world, one in desperate need of their transformed selves and whatever art they can add to it.

Appropriately—and dramatically—Gass concludes his final authorized book with “The Death of the Author” (1984) in which he discusses the phenomenon of a writer being removed from his work, a literal as well as a literary event in Gass’s case, he knew, and it was no doubt approaching more swiftly than most of us would want. That is to say, how is a work regarded when the reader has no clear sense of the soul who created it? The person of Homer has disappeared from the Iliad and the Odyssey altogether, the Beowulf poet is known only by the epithet of his work, and though (conspiracy) theories abound, Shakespeare the man exists only as little as one of his own ghosts brooding in the wings, never to be called clearly onto the stage. Unlike writers of the past, however, Gass lived in a time when his image and his voice were easily captured. Thankfully, there are copious video and audio recordings of the Master.

Gass writes, “The problem is not, I think, whether the author is present in the work in one way or another, or whether the text will ever interest us in her, her circle, her temper and times; but whether the text can take care of itself, can stand on its own, whether it needs whatever outside help it can get; whether it leads us out and away from itself or regularly returns us to its touch the way we return to a lovely stretch of skin.”

Like all authors, one imagines, Gass’s hope was that we shall indeed return to his work, that long and lovely stretch of skin, after he departed for some writers’ Valhalla where he will forever take tea with Rilke and Valéry, and perfect his French by conversing deep into the literary night with Flaubert and Colette. Meanwhile, for we few, we happy few, reading the Master remains, a Rilkean comfort he reminds us of in retrospect: “Though what has been celebrated is over, and one’s own life, the life of the celebrant, may be over, the celebration is not over. The celebration goes on.”

Notes

1. My dissertation was published under the title Trauma Theory As a Method for Understanding Literary Texts (Edwin Mellen, 2016). See Chapter 6 in particular.

2. There are several video and audio interviews with Gass that can be found online. A published book of interviews is Conversations with William H. Gass, edited by Theodore G. Ammon (University Press of Mississippi, 2003). Also see “The Ear’s Mouth Must Move: Essential Interviews of William H. Gass,” edited by Stephen Schenkenberg.

3. For writing this review I would like to acknowledge the generous assistance of Mary Henderson Gass and Catherine Gass. Among the other pieces of information they shared or confirmed is that there may well be other works by William Gass forthcoming, including his book on Baroque prose, an excerpt of which appeared in the inaugural issue of LitMag (spring, 2017); and a work known as “Marianne Moore’s Lexicon,” a teaching handout Gass used in his Philosophy and Literature course (spring, 1999).

4. Numerous videos can be found online of Gass reading from his work, but an especially fruitful one has been posted by the Lannan Foundation, titled “William Gass, Reading, 5 November 1998,” in which he reads excerpts from “An Invocation to the Muse,” “Emma Enters a Sentence of Elizabeth Bishop’s,” “Culp,” other various short bits from The Tunnel, and concludes with “A Fugue.”

5. I would like also to acknowledge the assistance of Joel Minor, curator of the Modern Literature Collection/Manuscripts in the Department of Special Collections, Washington University Libraries.

Credit for William H. Gass Photo: Herb Weitman/Washington University Archives