Introduction to Every Atom by project curator Brian Clements

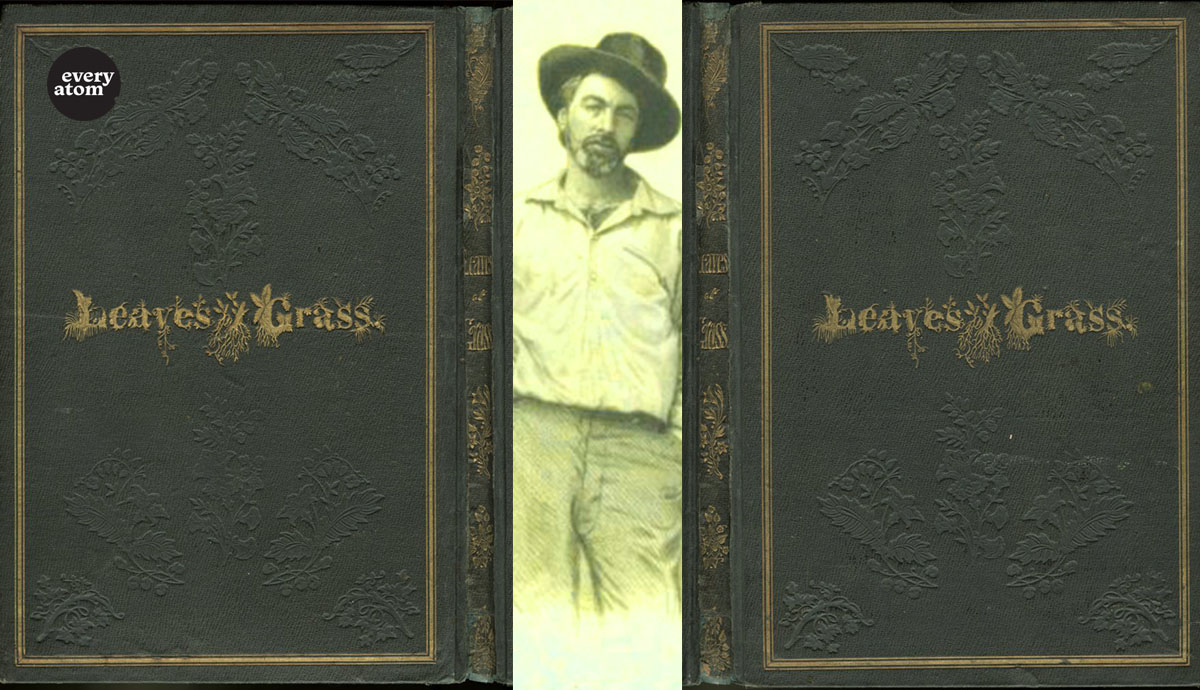

The first edition of the epochal Leaves of Grass was printed in 1855 in the midst of a full-blown revolution in the world of print. Giant new rotary presses cranked out newspapers by the hundred thousand; steam-powered trains and boats distributed them on a scale never before imaginable; experiments in graphic reproduction were rife. Whitman, perhaps unsurprisingly for a former newspaper editor and printer, enthused about the mood in the air, evoking the “press…whirling its cylinders” and using the term “steam” no fewer than a dozen times in the book.

But Leaves of Grass was famously printed on an old-school hand press, in a small Brooklyn print shop known more for its legal forms than poetry debuts. The 1855 Leaves was, consequently, a janky piece of printing, with drifting type and uneven inking—punctuation and whole words disappear in many copies.

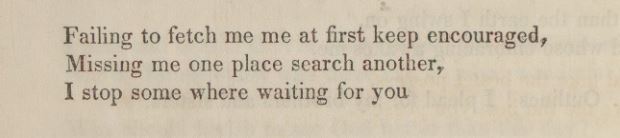

The legend is that Whitman was in the shop, carefully tending the production of this potentially life-changing book. So it’s surprising to see, at the culminating moment of the monumental opening poem that would come to be known as “Song of Myself,” the slip of the double “me,” and the missing period at the end.

We can give the poet a pass on the period, which in fact appears in several existing copies, and probably broke off or fell out of the form unnoticed. But there are plenty of patent mistakes, some of which were corrected and others not, to be found among the copies of the 1855 Leaves. In the preface, an upside-down n was at some point replaced, returning “aud” to “and,” for example. But on page twenty-three there’s a doozy of a transposition:

In walls of abode, in canvass tents, rest hunters and trappers after their day’s sport.

A page later is another instance of doubling that went unnoticed:

This is the the tasteless water of souls...

Then again: we don’t have to see “me me” as a mistake. Might the double me be the “me” and the “Me myself” Whitman refers to in the poem? or might it, thought as a chiasmus, signal a reciprocity of encouragement between both reader and speaker? The flubs in the first Leaves vibrate with the humanness of the maker of the poem and the makers of the book.

And were there, in the end, any real “mistakes,” as Whitman envisioned things? He used the term “perfect” forty-six times in the first Leaves: it was central to what Whitman took as his task. But in all cases the most basic, persistent tendencies, the overarching forces, are what make for perfection, rendering even broken details integral with a whole. “What is called good is perfect, and what is called sin is just as perfect,” we are asked to understand. “How beautiful is candor!” Whitman writes in the book’s preface; “All faults may be forgiven of him who has perfect candor.” The encouragement offered in this passage can be a key both to the mystical patience its speaker demands of us and the challenge of reading the surface of a visibly human text.