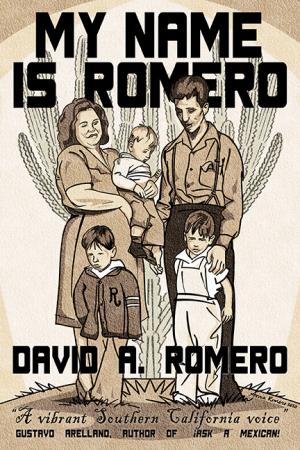

Some Latino poets like Willie Perdomo dish out the grit of living on the margins with superb poetical musical cadence in his 2014 The Essential Hits of Shorty Bon Bon: Poems. Other writers like Daniel Borzutzky—a 2016 National Book Award Winner for The Performance of Becoming Human—immortalize the monumental horror of terror and torture of being “Othered.” What makes David A. Romero’s book My Name Is Romero a good addition to the Latin@/x canon is the honesty of the subject matter. The title of the book is not simply what it implies—the centering of the “Self”—of one Latino. Instead, it’s an informed, intrepid, and at times, painful revelation of thoughts and dialogue that lie unspoken in our brains and amongst many Latin@/xs, and in Latin@/x communities.

The book’s title My Name Is Romero feels like a salute to Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzalez’s 1967 epic poem titled, “I Am Joaquin.” While Gonzalez’s poem encompasses the historical totality of what it means to be a Chicano, Romero’s identity poem takes on Latinidad in a more straightforward manner. At the same time, its echo is emotionally complicated. His poetics is rolled in the empirical and intellectual politics of a Latino’s identity construction in the U.S.

The book’s title My Name Is Romero feels like a salute to Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzalez’s 1967 epic poem titled, “I Am Joaquin.” While Gonzalez’s poem encompasses the historical totality of what it means to be a Chicano, Romero’s identity poem takes on Latinidad in a more straightforward manner. At the same time, its echo is emotionally complicated. His poetics is rolled in the empirical and intellectual politics of a Latino’s identity construction in the U.S.

The book begins with a culture clash. In the introductory poem “My Name Is Romero,” our author recounts how his name is mispronounced. Romeo? Or Romero? Is any name just as significant? Contrary to Shakespeare’s idea that “a rose by any other name is just as sweet,” the renaming or mispronunciation of Romero’s name is just the tip of what can be considered microaggressions.

In the poem “Sweet Pochx Pie,” he writes: “And rolling R’s seem as silly to me / As caricatures of twirling mustaches / When saying my own name properly / Makes me feel like Zorro.” The rolling of the “r’s” highlights a poignant theme of how the use of language is related to the ability of crossing ethnic and racial borders, and how language is used as a measuring tape of a Latin@/x’s level of Latinidad. Throughout the book Romero deals with the conundrum of Spanish as a weapon and a place of healing.

As you can tell by now, the poems are ethnographic and derived from the perspective and duality of being able to “pass” as a white Mexican but mired in the purgatory of being “Othered.” The progression of the poems reads like a coming-of-age story—a geschichte, where the dialogue travels between the evolving identity in the present and the identity shed from the past. Through his poems the “white”/ “passing” Mexican is as much an alien amongst Latin@/x communities as well as in the mainstream. The “white” or “passing” Latin@/x is another foreign threat that can never fully be permitted or assimilable into U.S. society. The sadness of being forever in limbo, between the world that Latin@/xs actually inhabit, and the one they imagine and struggle to create for themselves, runs in the veins of Romero’s poems, “Make me more Mexican / A simple statement / A declaration / A cry for help!” he demands in his poem titled, “Make Me More Mexican.”

Inclusion versus exclusion is a main theme in this collection of poetry and is reflected in a multi-layered way. Romero is not afraid to engage in huge personal critiques of himself. He shares a childhood memory on how he rejected his working-class father: “Gorilla arms / The arms that built our house / The arms / That hugged my mother / That carried me as a child / I looked at those arms / That Sunday morning / And told him, / “You look like a gorilla.””

Romero also calls to task well-known actors and comedians like Edward James Olmos and Katt Williams exposing their rise to fame through waffled racial power relations. For instance, regarding the comedian Williams, Romero does not hold back his hostility on what he perceives to be Williams’ embedded racism, “Even a pimp in parody / Becomes a prostitute / When he performs in / Phoenix, / Arizona / Where our dreams go to die…” Lines like these point to the book’s angry political dimensions against pop artists that sell out to the mainstream’s institutionalized racism. In this way, Romero’s poetry attempts to tackle the binary of U.S. racial thinking. The idea that race only affects those who are racialized is implicated in the progression of his poems. He offers us a perspective on how the Black-White binary complicates the problematic and ahistorical ways in which Latin@/xs experience racism.

In My Name Is Romero, our author reminds us that Latin@/xs have experienced an arduous journey in the U.S. that includes coerced labor exploitation, internment, racist stereotypical representation, sweatshops, and sexual slavery. His voice is a continuation of how poets, through tough truth-telling, organize, and mobilize against power.

By the end of his book, Romero is commissioning his readers toward solidarity with him and his family, and the need to remember Latin@/x history. In the poem “Our Name is Romero,” our author comes full circle: “We do this / As our father had done / Remember those who have come before / Those we know / And those lost to history / Our name is Romero.”

In a painful but thoughtful journey, Romero gives his readers license to contemplate their lives on the border of race, language, skin color, food, and religion. In that way, the poems are a space of agency where we are drawn into the author’s experiences, his anger, and his truths as we interrogate our own gaze and judgments of his life. With these poems Romero is another important voice that continues to expose the erasure of the history of struggle and progressive individual acts of validation and resistance of Latin@/x communities.