“When the virus spreads / through the herd…” —the premonitory nature of the opening line to Todd Davis’s seventh poetry collection, Coffin Honey, anchors the tone, vision, and narrative of an incredibly nuanced and layered book. More than just a collection of singular pieces, these poems weave together into a larger narrative arc with characters and conflict, settings and images, themes and voices that build a shared landscape being ravaged and slowly dying of various diseases. Coffin Honey is written by a poet with deep knowledge of the land and empathy for his subjects, who delicately and expertly explores how we suffer and pay for our sins, how we can rewild into redemption, and what of this anthropocene is worth saving.

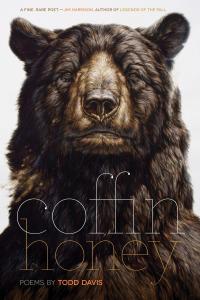

The main character of Coffin Honey is Ursus, a bear that shows up in dreams, that stalks the woods, that bears witness, that brings reckoning to those who deserve it, that outlasts all of us. As Davis observes in “Bog Parable,” “Bears are born understanding the eternal,” and with that Ursus acts as the intermediary between our world and the world of Coffin Honey. Ursus is an echo of us and what we once were back when we were part of this land. In “Museum: Ursus americanus,” a collection of bears that were stripped of their fur “look / so much like the ones / who did this” remind us that we are not that dissimilar from the world which we carelessly destroy. Ursus is a sacred character and with each poem Davis unfolds a narrative that Ursus is the god of.

The main character of Coffin Honey is Ursus, a bear that shows up in dreams, that stalks the woods, that bears witness, that brings reckoning to those who deserve it, that outlasts all of us. As Davis observes in “Bog Parable,” “Bears are born understanding the eternal,” and with that Ursus acts as the intermediary between our world and the world of Coffin Honey. Ursus is an echo of us and what we once were back when we were part of this land. In “Museum: Ursus americanus,” a collection of bears that were stripped of their fur “look / so much like the ones / who did this” remind us that we are not that dissimilar from the world which we carelessly destroy. Ursus is a sacred character and with each poem Davis unfolds a narrative that Ursus is the god of.

Instead of numbered sections, Coffin Honey is split into parts by “Dream Elevator” sequences that, through extended line breaks and long moments of white space, take us into the liminal world where narratives collide. The first and last “Dream Elevator” poems are about a boy who is assaulted by his uncle. The boy mirrors the land, he “descends / the shaft of sleep / into coal-burning darkness” into a world of “anthracite / scabs / veins emptied / no place left / to stick a needle.” His uncle “smells himself and considers / how sin stains the sinner.” The uncle understands he is a sinner and sees how he is stained by his nature, and yet this recognition does nothing to stop him.

The second and third are visions of our world once “the plague / which we made / which we are wipes” through us. There are only a few survivors left in a world with “No screens. / No buildings. / No cars.” that can only do “As we once did… scratching images / on the bark of trees.” These dreams show an apocalypse that will not come just from how we treat the land, but also each other. As we exploit the land, we exploit each other. The dreams collide with the rest of the collection when, in the last sequence, after raping the boy, the uncle is killed by Ursus after he “smelled the sin / and followed his hunger”, the bringer of justice, the one who understands how we must all pay for our sins.

In many ways this is a collection of poems narrating our own destruction, a cautious tale of things surely to come if we keep abusing the land as we are currently doing so.

In its darkest moments, this collection takes us into a post-apocalyptic world where “drones replace the shadows of birds” and “whatever sprouts, we eat.” There is a divide between rural, where meat and food comes from, and suburban, where the meat and food will go, where they “still sprinkle their lawns” while those back in the country “bed down in holes, coal-swollen tongues” ruining “the taste of meat.” Resources over community. Extraction and destruction. Disconnect and greed. Over and over, we see how we have been pushed further from each other through our lust for convenience and in that separation, all that is left is Ursus. Ursus who lopes through our dreams, who watches what we do, who brings justice to those who deserve, who catalogues this world so when we try to rebuild, we’ll know what is worth saving and remembering and building upon.

In many ways this is a collection of poems narrating our own destruction, a cautious tale of things surely to come if we keep abusing the land as we are currently doing so. Some may say that Coffin Honey offers little light, that it is too dark. However, Davis does offer redemption, resurrection, and a path forward, especially in the three poem sequence of “Ursus Grows Wings,” “Learning to Tie a Fly,” and “Lost Blue.” In each poem we see a lifting into, a reaching towards a new life, a transformation. In “Ursus Grows Wings,” the bear becomes saintly. His “Claws can write history,” but it’s his body “that presses the human mind...like the light that shines / around the heads of saints.” In “Learning to Tie a Fly,” a girl whose brother drowns learns to imitate life in order to create and capture it by attaching “plumage to sculpt the hackle, fashioning / with tenderness a lie to float across a riffle.” Yet, transformation isn’t always beautiful. Sometimes it requires destruction. “Lost Blue” shows a man who counts every native fish that still remains after a wildfire,

orphans of the lost

blue I’d hoped

to show my son

before the debt

of loving a place

broke him.

Yes, loving a place that is changing, rewilding, that some hold holy while others see only as a resource, will eventually break us. But what else is there to do? We must love these places, even in their most scorched and torn states, just like we must love ourselves and each other as we heal and transform.

In its most nuanced moments, in its larger storytelling self, Coffin Honey is a creation story, a collection of poetic myths of world-making built on the honest, detailed imagery of Davis’ writing that shows us how to survive, live, and be part of this world once again. It forces us to ask whether or not we are worth saving. If so, how do we exist in a way that complements, that gives back, that is not simply an act of extraction, but of being, of giving, of living? Follow Ursus. He’ll show us the way.

Coffin Honey is, and I don’t use this lightly, scripture meant to return to over and over. With each reading, another image is revealed, another story is told, much like how the men up on Blue Knob

possess one leg

shorter than the other, femur whittled

by thousands of hours wrestling

a plow along ridgeline,

we can’t help but be shaped by these incredible poems. Reading this book is witnessing a writer taking his craft to another level, an act of resurrection and of resilience, of choosing to be alive even in a world surrounded by so much death and destruction.

Davis sees, like “the oldest bears, with milky eyes, see through water clearly,” through the darkness of this world and takes us on a dream elevator to show us what we are losing, how we are suffering, and why we need to

return to the burial ground,

to make note in the ledger if any tree sprouts

from the bodies we planted.

Coffin Honey doesn’t give us light at the end, it doesn’t reassure, it doesn’t offer false hope. No, it does more, it acts as a sacred text showing how we got here and what we need to do to grow again, to become more than just the stains of our sins. We do not hold the answers. This world that we live in, that we extract and exploit, does. Watch, Davis demands, as the full moon rises “from the bear’s skull, / showing what she thought of us” and know that even though “it’s hard / to give up this life,” “we must. Others are waiting behind us.” Perhaps it’s time for us to move on, to be buried, to turn back to soil, but thankfully we’ll have these poems to help seed the next growth.