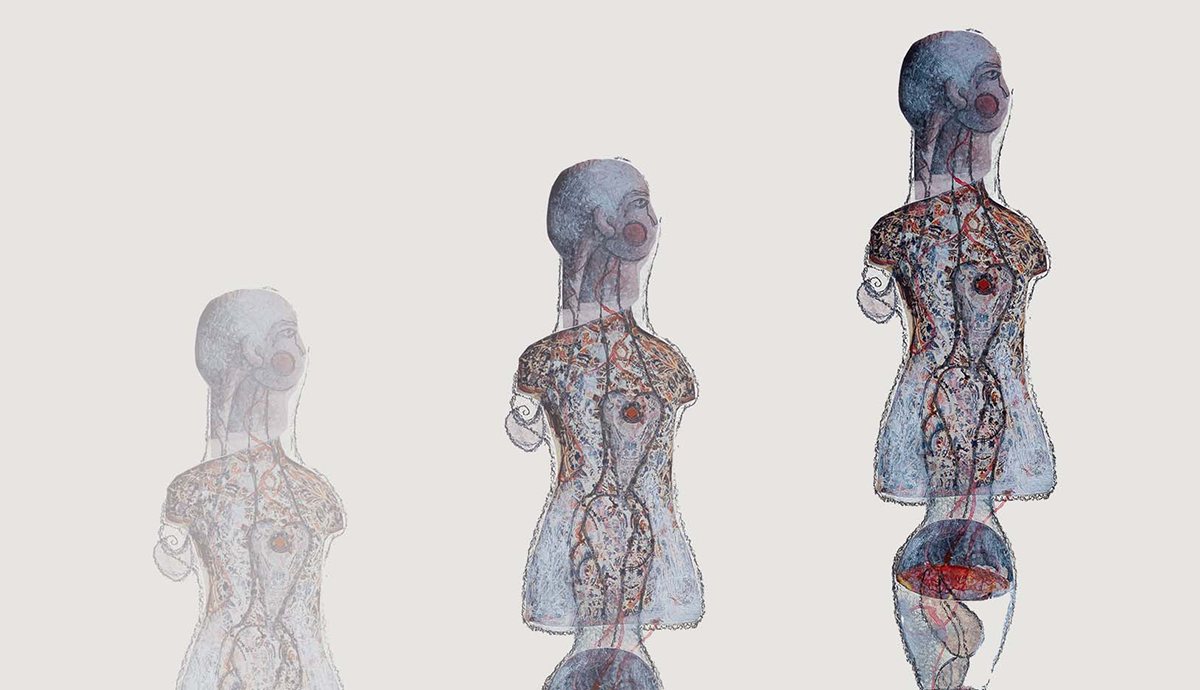

In Nawal Nader-French’s a record of how the mother’s textile becomes sound, text and textile become a conjoined tongue written in flight patterns across the sky, or page, or heart space. The breath “stitched into bones” builds a pattern, a body, a textile, a manuscript, a mother.

In Nawal Nader-French’s a record of how the mother’s textile becomes sound, text and textile become a conjoined tongue written in flight patterns across the sky, or page, or heart space. The breath “stitched into bones” builds a pattern, a body, a textile, a manuscript, a mother.

Written after Nader-French’s mother’s departure into spirit, this book attempts to breath alongside that spirit, refusing the finality of death, considering the tactile and textile nature of memory (the cloth, the perfume, the many marks we draw upon one another in relation, the wounds, and scars of being with, in existence). Nader-French’s book opens with the following epigraph from Mireille Calle Gruber: “word (mot) and death (mort) are consonant. One must work at moving in language at the risk of being a dead letter—of arrest (death sentence).”

The poems in this collection ask how one might capture the aliveness, the ephemera, the ineffability of our dead. I’m reminded of M. NourbeSe Philip’s quest to reactivate the voices of the dead lost to the ship Zong!. Her text surfaces those lost voices to the page in an act of anti-erasure, allows for the spit and gasp and agony of being drowned to haunt the vocalizations. And in her performances of this work, she becomes a version of a spirit doula ushering between the veil of the living and dead, hemming two realms together.

Nader-French’s work creates a similar gesture through the act of reconstructing the body/fabric of the mother while simultaneously deconstructing the language and meanings of the word “mother.” “When my mother died, I began with a move backwards in formal procession towards unpacking her in words emanated where I found her.” Like NourbeSe Philip’s work, a séance is being performed to arrive the dead back through the veil of the page, “like the scratching of an outline for a dress pattern.”

The specificity of this mother/haunting is felt as her outline fills the dress/page and as we learn of the details of the mother’s scarred body, this mother who becomes her own country that then becomes colonized. The mother’s history (political, social, personal) scratches her reemergence onto the mind of the writer and reader. The mother’s context and subtext are part of the fibers of her being, the mother as herself “half-crushed hollowed grooves—.”

mother as remnant

is as one untethered to language.

She is prefix and suffix

and she is uprooted. She is dissonance.

She is rhizome.

I also hear echoes of the work of Cecilia Vicuña in this text: “Quechua, the sacred language, is conceived as a thread.” / “But they did not write, they wove.” And Levinas’s ideas of the Saying and the Said. All of this an attempt to keep language living, like Emily Dickinson expresses in The Master Letters: “Are you too deeply occupied to say if my Verse is alive?”

Nader-French asks, “mother: / can a word atrophy?” Part lyric, part philosophical treaty on the nature of language in relation to death, and breath, her work moves beyond eulogy or ode toward the transformative potential of language to resurrect the other within us.

Verbum

It is the word; said to be the word of God; said to express action or

being; the logos, the rational principle said to govern and develop

the universe. To be exact, the smallest element that can be uttered

in isolation. Where to exist, it must utter the second person—incarnate

in a person.

One might read this work as a poetic reimagining of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, as the impulse toward resurrection, and the stitching together of disparate elements (via language and memory), pattern a body not quite like the original, but still create one that lives and breathes.

the work

To avoid damaging the work, when the mother is

complete, melancholia skulls atop her head and she is

hushed—

I read the “she” here as the author. Quiet now that her work of mothering the mother has been “carefully installed into textile, / exposing dissonance within the birth of her words.”

This book is a gorgeous debut from a poet whose work is both precise and awe-inspiring. a record of how the mother’s textile becomes sound is a book I will return to often. ⬤