In Rick Christiansen’s first collection, the speaker’s mother performs do-it-yourself surgery and extracts her child’s teeth with pliers. These images, among others, as told through the perspective of an older, wiser self looking back and that of a resilient child, resonate throughout this sinewy book.

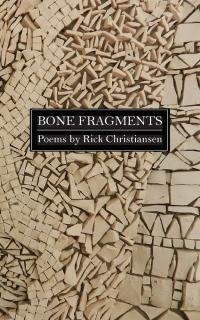

Published in 2024 by Spartan Press, Bone Fragments was written long before it met the page. As a writer in his sixties, Christiansen arrived on the poetry scene later in life, which is why his poems feel authentic and whole; the voice on each page is like another organ in his body, always there throughout his genesis. The poems, predominantly free verse, range from the haibun to dramatic monologue to confessional to lyrical. The speaker tackles a lifetime of topics that weave in and out of restrained contempt for an alcoholic, absent mother to that of an amused, loving grandfather to that of a man who still grapples with connecting the tissue between the splintered bones of his past and present.

Published in 2024 by Spartan Press, Bone Fragments was written long before it met the page. As a writer in his sixties, Christiansen arrived on the poetry scene later in life, which is why his poems feel authentic and whole; the voice on each page is like another organ in his body, always there throughout his genesis. The poems, predominantly free verse, range from the haibun to dramatic monologue to confessional to lyrical. The speaker tackles a lifetime of topics that weave in and out of restrained contempt for an alcoholic, absent mother to that of an amused, loving grandfather to that of a man who still grapples with connecting the tissue between the splintered bones of his past and present.

In the previously mentioned poem, “Baby Teeth,” told from the perspective of the speaker’s abusive, poverty-stricken mother, she confesses:

Some things just need

to happen. It’s for his own good. He will thank me when

his big boy teeth are strong and straight…

I will create a sterile field…

The same can be said about Christiansen’s poems, which engage a linear narrative, from the speaker’s earliest memories of making difficult choices to his current life as a loving grandfather.

As depicted in “Baby Teeth,” the most compelling instances of Bone Fragments involve choices of love and desperation. The speaker reflects in the opening poem with the same name as the collection:

My mother would disappear, sometimes for up to

a week. I would shoplift groceries at the Ralph’s in North Hollywood to feed my

little brother and myself. It didn’t feel like stealing.

I always took a list.

However, one of Christiansen’s strengths lies in combining a refracted childhood through connective, tender tissue. In the closing line of the opening poem, the speaker sets the tone by harkening to the ars poetica, one of a man who’s entered his golden years knowing that much of his younger ones were tarnished but refuses to let go of whatever shine remains:

I have built a life around listening to the music others make

And trying to match the syncopation. There is some peace

In slowly going deaf.

It isn’t really silence,

Just the absence of noise.

Christiansen’s speaker, like the author himself, who stumbled on poetry after retirement, goes from trying to find his rhythm to stepping into his own voice until the end of the collection, when the poems discover the strength in their fragility.

In “Cardboard Sleds,” the speaker fondly watches his grandchildren defy the seasons and slide down a hill on makeshift sleds. The speaker marvels not only at the innovation of children but also at the miracle of his life defying the impossible: much like a springtime sled, he’s arrived where he can feel the pain of his joints but also the comfort of his love, stating, “I sit on my patio and swallow their joy.”

And the speaker’s childhood memories aren’t always painful or fragmented. In the closing poem, “Words Float,” the narrator reminisces on his late father’s wisdom:

My Dad said that

when he was gone

he wanted to leave a hole.

He is gone.

His wish was granted and there is a hole.

Now I fill that hole with words.

Every day, I drop some in

and watch them descend into the pile.

The reader can hear the plink as the speaker drops his memories into the container of his first collection, from painful to nostalgic.

As one finishes Bone Fragments, one can only feel fulfillment and emptiness for those we love who leave us, as reflected in the last line: “I hope he is feeling comfortably full.”

Read the title poem from Rick Christiansen’s Bone Fragments.