NAR poetry editor Rachel Morgan reviews two new books: Requiem with an Amulet in Its Beak by Elizabeth Knapp and Tap Out by Edgar Kunz.

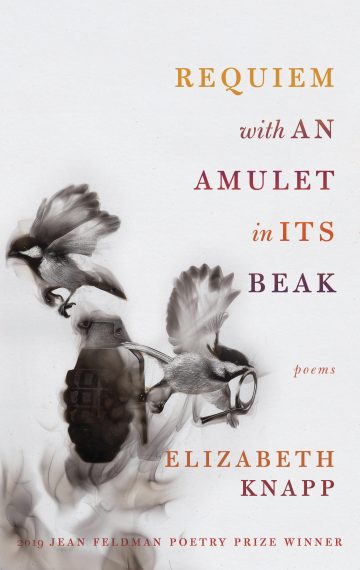

Requiem with an Amulet in Its Beak by Elizabeth Knapp, Washington Writers’ Publishing House, 2019, paper, 73p. $16.95 •

Requiem with an Amulet in Its Beak by Elizabeth Knapp, Washington Writers’ Publishing House, 2019, paper, 73p. $16.95 •

Elizabeth Knapp’s second collection, Requiem with an Amulet in Its Beak is the 2019 Jean Feldman Poetry Prize Winner, and three poems in the collection were finalists for the 2019 James Hearst Poetry Prize. This collection teems with modern laments that feel both private and collective. The recent loss of music icons like George Michael, David Bowie, Prince, are refrains, “a track on the mix- / tape of someone else’s youth” that build the elegiac nature of the collection, but it’s not the lost talent that’s lamented, rather something more slippery, illusive, communal, a postmodern American zeitgeist that is both alive while mortal, especially in the current political climate.

Poems with titles like “Is That a Gun in Your Pocket” and “Like Running into Hillary Clinton in the Woods” speak to living in American today. The ironically titled poem “Fourth of July” bristles with criticism of an ignorant but opinionated America, “If you asked / two of us the same question, you’d get / six different answers, depending / on which side of the news you’re on. // …Some of us are sleeping. / Some would kill us in our sleep.” And yet, a consumer culture surfaces in other poems eloquently and inextricably linked to personal grief, “All summer you’ve been dying / in the shopping cart of my mind.”

For all the poems that work within the traditions of tractate, requiem, threnody, elegy, lament there are also ghosts, angels, and children offering not an afterlife, but an alternative life. Emily Dickinson and Kurt Cobain appear throughout the collection as muse and anti-muse, respectively. A series of “Self-Portrait” prose poems invoke Kurt Cobain, his childhood, his suicide note, and his “arena of stardom,” while being a kind of ars poetica, discussing the creation of poetry, “The beauty of metaphor is that the angel can be just an angel if you let it.” The speaker in many of the poems is concerned with the process of writing, of creating, of not wasting time.

Toward the end, the coyly titled, “The Cemetery is Full of People Who Would Love To Have Your Problems,” defines the more collective concern, “the fear of wasting another year of your life,” and asks more questions than it answers about how creators, poets especially, motivate themselves especially against a backdrop of mortality and political and personal stagnation. By calling on the icons of Kurt Cobain, Prince, and Anthony Bourdain, the allusion to suicide and addiction, especially in the lives of artists, simmers under the surface.

Requiem with an Amulet in Its Beak dissects our contemporary moment, in an age of endless public confession on social media, while existing in this digital ago also prompts secrets and manipulated messaging. When the personal becomes public—Monica Lewinsky’s blue dress, Cindy Sherman’s Instagram account, our lives lived “in the desert of the real”—is when distance between artist and artifact becomes greater. Knapp adroitly settles into this space and offers her readers a lament and a liturgy for living in our times.

Tap Out by Edgar Kunz, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2019, paper, 95p. $14.99

Tap Out by Edgar Kunz, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2019, paper, 95p. $14.99

Edgar Kunz’s debut collection Tap Out is a knock-out; one hand hits and the other holds you at a distance so you can survey the aftermath of addiction, poverty, and divorce. These poems dig and pitch with realness, while the short sentences say more by what’s left out. They are “miracles of pain.” In the manner of Nick Flynn and Phil Levine, these poems summon estranged fathers who struggle in addiction and work in the dust and grit that coats blue collar America. The pain is personal as much as it is endemic to “every downtown / business” of “the failed / industrial towns of New England // … their dead cars / their factories and silk mills converted / and upsold to commuter.” In a world held together with WIC, “the half-offs, the buy-one-get-ones,” and ShopRite, a young boy comes of age in a place where masculinity is a measure of worth, but the measuring system is broken by drugs, poverty, and violence.

Twice Kunz uses the image of an injury that doesn’t “hurt until later,” and that seems a fitting descriptor for these poems, many of which revisit the perspective of a thirteen-year-old boy who is “already sick / to death of this place,” who steals supplies from a neighborhood reconstruction worksite after a house burned down: “roofing tiles, fresh lengths of pine / and vinyl siding we carried back / in our arms. I can’t remember, now, / what we were making. If we ever / made a single useful thing”, who loses a friend from gun violence. Much of the neglect and poverty does hurt later in a hastily planned marriage: “Backyard. July. My mother / will cook, my brother will DJ” and its divorce just as hastily arrived. After divorce, the speaker begins to recover in the vast western spaces of Colorado and California while crashing with friends or housesitting: “I’d lie in their bed under three heavy / cotton blankets and worry / about the horse and the dwindling / supplies. It was a life and it was not / mine,” and it is this out-of-bodiness that makes these poems so inhabitable.

What makes Tap Out different from books borne out of poverty and addiction is its lack of blame or forgiveness. Systems fail and people fail. It is not sentimental or stark, even the “I” that recounts the past in the restrained lyricism of the couplets seems dazed and tells its story in plain speech. Much like a blow to the head or an accident, the realization happens after, not before or during. The collection opens with an important place-setting poem, the father is “in a van by the Connecticut River” with “a pair of extra pants bunched / into a pillow,” and he’s trying to recall all that’s he’s lost: a wife, sons, a home. Alone, hundreds of miles away, the speaker has to figure out how to be a man in a patriarchy that harms itself as much as it harms others, how to be a son who needed a better father.

Tap Out is as much about where we come from as where we are going, and Kunz, with his vulnerability and power, will be an exciting emerging voice to follow.