A Review on Elegy and Kelly Rowe’s Rise above the River

While elegy is a long-standing tradition in the literature of loss, critics have recently turned their attention to theoretical shifts in the continuum of these memorial poems, proffering a new understanding of grief. One might ask: is it ever possible to move fully beyond mourning? Increasingly, contemporary critics and clinicians suggest that mourning should be considered never-ending and the connection with the deceased should be encouraged rather than discouraged. This idea of protracting grief contradicts the Freudian notion that bereavement involves the survivor severing ties with the lost loved one, or the culmination of the five stages of grief ending in closure, freeing themselves to form new attachments and let go of the past. Expressive of elegiac longings, poets in the modern age refuse consolation and cede to the endlessness of grief.

While elegy is a long-standing tradition in the literature of loss, critics have recently turned their attention to theoretical shifts in the continuum of these memorial poems, proffering a new understanding of grief. One might ask: is it ever possible to move fully beyond mourning? Increasingly, contemporary critics and clinicians suggest that mourning should be considered never-ending and the connection with the deceased should be encouraged rather than discouraged. This idea of protracting grief contradicts the Freudian notion that bereavement involves the survivor severing ties with the lost loved one, or the culmination of the five stages of grief ending in closure, freeing themselves to form new attachments and let go of the past. Expressive of elegiac longings, poets in the modern age refuse consolation and cede to the endlessness of grief.

The labor of mourning, as Freud first described it, entails a fixation on the dead, a process of obsessive recollection, replacing an actual absence with an internalized imaginary presence. The dead may have left us, but they endure within language and must rely on others to exist. Within this crucible of grief, the spirits of the dead appear paradoxically within the very words that claim they have vanished. With a very specific task to perform, the elegist’s labor of grief seeks to transform mourning through the remembrance of the dead into a futureless memory.

Elegies, paradoxically, are an art that will never die. Loss creates a vacuum within, and we cannot retain the same identity after someone close to us dies.

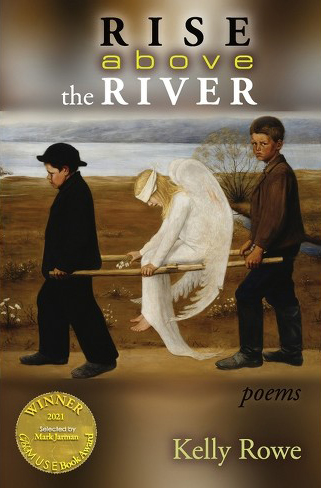

I can think of no better example of transmuting difficult mourning into an art form than Kelly Rowe’s prize-winning book-length elegy for her brother, Rise above the River, the lyrical narrative of an older sister grappling with the meaning of his senseless suicide. Each meaning unwraps yet another meaning as the poet-detective sets out to solve the mystery of what happened to her brother to cause his estrangement, who cared about little besides his own needs and was hurtful to those who cared for him. In Rowe’s imagination, he dies not once, but twice, both in life and in death, just as he appears in the poems as a double: the angelic boy he once was with the soprano voice, the inner representation that she clings to, and the sociopathic man who continued on a path to self-immolation and self-destruction, both emotionally and physically. The poet identifies herself as a detective encountering a “Cold, Cold case.” Her goal is to revive him and, quite literally, see him rise above the river where he played as an adventurous boy. Hence, the poet’s task is two-fold: to tell the story without embellishment while simultaneously elevating her brother into a modern myth, alluding to the story of Antigone, who breaks the law to bury her brother, taking the part of Ismene, the sister who refuses to go along with the plan. However, when Antigone was condemned, Ismene was filled with remorse and begged to be allowed to join her in death, which leads to their mutual demise. What she saw festering in him was a death-in-life: “How could I know / that I was writing to a corpse / imploring it / not to rot.”

The allusion to Ismene is compelling because of the trope of burial and covering up, smothering the body with sand and earth; Rowe’s nightmare of her brother drowning becomes her responsibility. Her brother had been sexually abused by an overly attentive teacher, something that haunts her brother, yes, but also the other adults who did not intervene, who may regret trying to cover it up or bury it alive.

The book opens with a particularly affecting poem, “Invitation to the Reader”:

I’m waiting for you;

I’ve opened the window wide;

you can rest in the garden,

you can fold your wings,

and I’ll read aloud to you

in the wakening light

of memory

a detective story

I have to whisper: everything

I am about to tell you

is invented, every word

of it is true.

To tell the story of the dead, the poet must invent what could be hypothetically true because the dead can’t speak to its veracity. The dead remain dead, and the only thing that has the possibility of being altered is the manner in which the living reinvent the dead. Divided into six sections progressing through time and flashbacks, the explicit facts surrounding her brother’s suicide at the age of forty-six are still shrouded in secrecy. By bringing the lost person back to life in the life of the poem, the elegy shatters an illusion of loss to reclaim that person to whom one’s grief is attached. In the poem “The Way Memory Works,” a painting that “used to / hang in your parents’ living room” is suggestive of a narrative that the casual bystander would not see, where a man is seen fishing on the icy river (an eerie resemblance to her brother) as the boat hits a crack, and “a spill of water seeps” in. Trauma, such as a sibling’s suicide, stops time in its tracks, and nothing is certain:

Impossible to know for certain

what the artist meant

or to reach the man in time,

as he sits surrounded by the growing dark

circle of water, beyond the bare black trees,

the path obscured by snow.

In addition to seeking solace through ritualization and traditions, traditional elegists lament the one lost while still expressing praise and admiration for the idealized dead. From Milton’s “Lycidas” to Shelley’s Adonais and Tennyson’s In Memoriam, traditional elegy evokes the memory of the dead to impel the imagination seeking a spiritual reunion in the underworld of grief and turmoil. However, for Rowe, mourning may become a never-ending process that defines the mourner’s sense of self, continually trying to come to terms with death without reaching any closure—hence section II is titled “My Cold Cold Case” as she tries out different theories that might explain why her brother became increasingly remote and unreasonable, angering the speaker who has no place to direct her anger than at herself, which turns into melancholia. As Freud explains, in mourning, the inhibition and loss of interest in anything not associated with the deceased are fully accounted for since the ego is so painfully absorbed by it.

Elegies, paradoxically, are an art that will never die. Loss creates a vacuum within, and we cannot retain the same identity after someone close to us dies. The death of a brother becomes the death, symbolically, of the sister—her role now terminated. Some elegies rant against the cruelty of losing a loved one while others offer conciliation. The mourner blames herself for abandoning him to go to college: “I left you behind: a childhood favorite / forgotten on a shelf. . . Now I’m landlord of a vacancy, / no creak on the stairs, / no smallest sign. I long / to be haunted, but / you have left me behind.” She cannot be haunted because he is the one going forward; she cannot look behind her because he is not there. Rowe’s memory of her brother is a split screen; before the alleged abuse and after, or the angelic boy obscured by the presence of someone without the capability to love, to one far more cynical: “I went to college, you to sixth grade; / when I saw you again, something / a little sly blew around your face / like a gray rag covering a window / that used to stand open. / I didn’t understand / that I’d never look in again, / and even if I could, the room was vacant.”

The vacancy is what is now within her signifying the loss. The speaker then speculates on the role the teacher played in damaging her brother and has a fantasy of arresting her: “After forty years? / Not an option. / Witnesses now are ghosts, / the crime scene plowed, replaced / by mansions and an artificial lake....” Of the senses, Rowe emphasizes sound, whether it is God’s voice (a God she confronts to speak to the misery of life), the soprano voice of her brother singing, or the inferred voice of the poet herself reading and writing simultaneously.

It may be that all poetry is about loss in one way or another; every language is an elegy to itself.

Listening for the deceased’s voice is a phenomenon that recurs frequently in grief, something that clinicians have observed, especially in children. During the first stage of mourning, the bereaved may believe that she hears the return of a familiar voice, or sees the face in a familiar place; hence, Rowe’s images of mirrors repeat throughout the book. God becomes a character in some of these poems, and clearly, the speaker blames God and refuses consolation or solace in religious salvation and the afterlife. The consolatory powers that religion typically brought to bear against the meaninglessness of death are now left to the poet’s ethical devices as she considers what death is and how to work through grief. In this elegy, like so many of the modern elegies that mark a departure from the earlier pastoral elegies that express lament, the poet remains attached to the loss and perpetuates the pattern of resurrecting his memory only to see him fall yet again into the deep waters of oblivion. In trauma, forgetting is self-rescue, and numbing is the armor that protects us from what consciousness can’t bear.

The poems that follow midway in the book chronicle spots of time when the poet-speaker recalls her brother’s recalcitrant behavior, her anger projecting back onto herself, along with God’s indifference. We learn about her brother’s addictions, incarceration, and exploitation of his sister’s generosity. Grief shapes this fractured world into unbrokenness—but never makes it whole. Throughout the narrative, the boundaries between death and life become blurred, as when his sister sees him through the window of the bus after their mother’s funeral—vague and undifferentiated from the dark glass, a mystery shrouded in mystery. He appears to disappear. Although the work of mourning is initially rejected, it requires deep and absorbing focus. At the end, the sister’s redemption comes with her understanding that the dead are never dead; they live and grow with us. Instead of manifestly accepting the Christian salvoes on death or the promises of transcendence through communion, Rowe works through her pain, guilt, and loss, and breathes beauty back into life.

Having just completed a critical book, The Poetry of Loss: Romantic and Contemporary Elegies, I believe that elegiac mourning involves the transformation of the meaning and effects associated with one’s relationship with the lost person. The goal of which is to permit one’s survival without the other’s presence in life while at the same time ensuring a continuing bond with the deceased. It may be that all poetry is about loss in one way or another; every language is an elegy to itself. The word substitutes for the missing object, fundamentally repressed and literally forgotten inside of language. Kelly Rowe’s finely crafted poems in Rise above the River tell a very human story and are an important contribution to the literature of loss. ⬤

Recommended

A Review of When We Were Gun: A Narrative Poetry Cycle by Deborah Schupack

A Review of Apostasies by Holli Carrell