The Ballad of Ollie Jackson

The following day, March 11, Stack Lee died of tuberculosis in the penitentiary hospital.

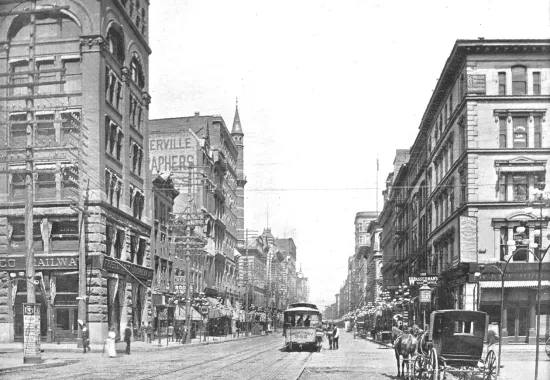

He had actually been pardoned by the governor on Thanksgiving Day, 1909, following a decade-long clemency campaign by his friends and allies. But he’d been locked up again in early 1911 after taking part in an armed robbery and assault. By that time, his legend was fully launched; songs about “that bad man, Stagolee” had been heard throughout the American South and as far west as Phoenix, written up in the Journal of American Folklore, performed on vaudeville stages, and published as sheet music. There may have been trace elements of this spreading folk-fame in the coverage of Stack Lee’s reincarceration. The papers made no mention of his musical alter ego, but the man himself, suspiciously, seemed to have grown in stature during the dozen years he was out of public view. The Star described him as “at one time the leader of the colored smart set in St. Louis.” The Post-Dispatch recalled Stack as “formerly a negro politician” who “preceded Ollie Jackson as proprietor of [the Modern Horseshoe Club].” Stack Lee had been both notorious and well-connected prior to his killing of Billy Lyons, but he’d also been a hustler who owned no property, oversaw no businesses, and floated from one boarding house to another. He’d pawned his gun for a dollar in 1894, and when he’d walked into Curtis’s saloon the following Christmas night, according to one witness, his first words had been, “Who is treating?” There’s no evidence that Stack Lee ever enjoyed anything like Ollie Jackson’s wealth or influence, and he’d been in prison for eight years by the time Jackson opened the Modern Horseshoe Club.

The articles are wrong, in other words, but also helpfully illustrative of how both men were perceived. It’s especially revealing to see Stack Lee misremembered as the Ollie Jackson of the 1890s. That’s how synonymous Jackson’s name had become, by 1911, with sporting-world success.

So how was the other “Ollie Jackson” faring? The song probably enjoyed a brief period of popularity in its early years, and it clearly had legs. But as it wandered it seemed to lose itself, blurring and merging with other ballads. It doesn’t turn up in the historical record until 1924, when a man from Indiana sent some fragmentary lyrics he’d learned “in the Ozarks” to the folklorist Robert W. Gordon. They concern a gambler who “shot six bits,” killed a bartender’s son, sipped some beer from a silver cup, and did some other things the letter-writer could no longer remember. The gambler’s name, improbably, had become “Olive Jackson.” Another folklorist encountered a version in Big Laurel, Virginia, in 1942. “I heard it a long time ago,” the performer told him. “Don’t remember where or when. It was made up about a fellow named Ollie Jackson killing another man in a card game and being sent to the electric chair.” He, too, recalled only a few verses:

The judge he said to him,

With teardrops in his eye;

“I’m sorry, Mr. Jackson,

But your poor boy’s got to die.”

If you lose your money,

Learn to lose.

The closest “Ollie Jackson” ever got to a studio recording was probably Paul Clayton’s 1956 performance of “Spotty and Dudie” on an album of folk songs he’d collected in the Cumberland Mountains:

Little Dudie was a gambler,

Spotty was a saint,

Let’s go down to the old Black bottom,

Have a last card game.

Every man oughta know when he’s losin’.

The song’s familial resemblance to “Ollie Jackson” suggests that folk-music composition is itself a game of chance: As Will Starks’s version has it, “Ollie Jackson was a gambler, / Dick Carr was the same—/ ‘Let’s go on down to Bill Curtis’s place / Where they havin’ a big crap game.’” Clayton’s characterization of Spotty as “a saint,” rather than “the same,” probably says more about the role of mishearing in song transmission than it does about Spotty’s sanctity.

An “Ollie Jackson” variant in the archives of St. Louis University preserves an even more memorable mondegreen: While Ollie and the saloonkeeper have retained their names, Dick Carr has become “Deacock.”

Ollie Jackson was a gambler;

Deacock was the same.

They’d walk into Mister Curtis’

And have a big crap game—

“Crying all I got’s done gone.”

That version had been performed by “an old citizen” of St. Louis in about 1955 and transcribed by Nathan Young, a beloved local judge, folk-historian, and raconteur. In an introductory paragraph, Young makes it clear that while he, personally, remembers Ollie Jackson well, the song itself is an obscurity even in its own hometown:

The following is perhaps the first time this ruddy ballard of St. Louis sporting life when it was at its heigth has been written down. The central character, Ollie Jackson, was a well-known gambling man … . He was six foot, and a handsome brown skined philanderer who had a share of notches on his gun. He owned ‘The Modern Horse Shoe Club’ at 2305 Chestnut street [sic].

Even the seventeen verses that Will Starks sang for Alan Lomax in 1942 may be evidence of the limited impression “Ollie Jackson” made. Their striking fidelity to actual events suggests not only that Starks had learned the song while it was still young but also that he hadn’t subsequently been exposed to other versions. “Ollie Jackson” just wasn’t getting around the way “Stagolee” was.

Of course that’s not surprising. Levee-camp workers, roustabouts, field hands, and prisoners were improvising new songs about local gossip on a daily basis, and hundreds of folk ballads must have flared and faded for every one that caught fire. But, again, “Stagolee” and “Ollie Jackson” were ballads of Black men who had shot down rivals for seemingly trivial reasons in the same man’s saloon within six years of each other. The two characters were, in a sense, vying to occupy the same folkloric space, and it’s hard to shake the sense that one’s success came at the other’s expense—that there wasn’t room enough for both of them.

One of Stack Lee’s advantages was timing. The killing of Billy Lyons had several years to establish itself as a musical set-piece before Ollie Jackson’s more sensational shootout. Stack Lee also had a catchier name. In fact, the name’s catchiness was probably the reason Lee Shelton had adopted it. One of the most popular men on the Mississippi River in the late nineteenth century was Capt. Samuel Stacker Lee, who ran steamboats out of Memphis for his family’s company, the Lee Line. His name was always “Stacker Lee” or “Stack Lee” in the newspapers, where it appeared regularly. His celebrity in Memphis, according to the Southern historian Shields McIlwaine, was such that there were “more colored kids … named Stack Lee than there were sinners in hell.” In 1902, twelve years after Stacker Lee’s death, the Lee Line launched a new craft in his honor. While Ollie Jackson was rolling through the red-light district in his “Modern Horseshoe” mobile, a 225-foot steamer, “the swiftest stern-wheeler ever built,” was churning up the river from Memphis to St. Louis with “STACKER LEE” on its side—a floating billboard for the folksong. And of course the name had a host of associated meanings and implications, most of which harmonized quite nicely with the legend. “Stag” connotes virility, strength, and self-sufficiency; “Stack” suggests flushness and a hot hand: one of the steamboat’s nicknames was “the Stack o’ Dollars.”

Another advantage that Stack Lee’s story had over Ollie Jackson’s was an objective correlative, a physical symbol of the story’s emotional content: the Stetson hat. There are no clues in the trial documents as to the maker of Stack Lee’s hat, but it’s a Stetson in the oldest known version of the song, transcribed just fourteen months after the killing, and that iconic accessory has been standing for Stagolee’s lethal pride ever since. In his book Stagolee Shot Billy, Cecil Brown recalls a “well-known black painter” telling him that “it is impossible to understand what Stagolee is about until one understands that Stagolee ‘wouldn’t allow anybody to “touch” his hat.’” The lesson of “Stagolee,” Bob Dylan has written, is that “a man’s hat is his crown.”

“Ollie Jackson” may have been doomed to irrelevance from the moment some singer put dice in Stagolee’s hand. As the scholar John W. Roberts has noted, the heroes of the Black “badman” tradition—unlike those in white outlaw ballads—were typically “not the professional criminals, but rather their victims who responded to victimization with violence.” When Stagolee became an aggrieved gambler who killed a man for cheating him, he stole Ollie Jackson’s story.

That, in turn, allowed his songs to swipe the one card that “Ollie Jackson” was still holding—that wonderful clear-eyed admonition, “When you lose your money, learn to lose.” Furry Lewis made it the refrain of what would become one of the most beloved versions of the Stagolee ballad, his 1927 recording of “Billy Lyons and Stack O’Lee.” The line is now so closely identified with the Stagolee tradition that, in the Lomax Digital Archive, the text accompanying Will Starks’s “Ollie Jackson” notes that it “employs the Stagolee tune and oft-used chorus to tell a similar story …”—the implication being that “Ollie Jackson” took its hook from Stagolee.

But Lewis’s lyrics show that the reverse is true. For one thing, they describe a conflict between Stack and Billy over “six bits,” which, again, was the exact sum that caused Ollie Jackson and the Carr brothers to reach for their weapons. Lewis also sings of a woman falling to her knees and crying “Don’t shoot my brother, please!” In the hundreds upon hundreds of extant Stagolee songs, that is (to my knowledge) the only reference to Billy Lyons’s sister, and she’s pretty clearly there to justify a line lifted from “Ollie Jackson.” As the gifted lyrics exegete Chris Smith explains in Blues & Rhythm magazine, “‘Don’t shoot my brother please’ makes better contextual sense in ‘Ollie Jackson,’ where two brothers are indeed shot, and is evidence that the direction of transmission was from ‘Ollie Jackson’ to ‘Billy Lyons and Stack O’Lee.’”

Ollie Jackson may have won the battle for bragging rights in turn-of-the-century St. Louis, in other words, but Stack Lee won the long game. Ollie was by far the more formidable man, and his signature act of badness was preserved in a blues ballad that traveled; he was well on his way to becoming one of the iconic badmen of Black folklore. But, like a river accepting a tributary, the Stagolee legend absorbed him.

* * *

The wallpaper in the sitting room of the Modern Horseshoe Club depicted elks pursued by hounds. It was a curious choice for an Elks lodge annex, but perhaps a fitting one, given the club’s perpetual hounding by police.

Ollie Jackson was breaking plenty of laws—pretending a saloon was a members-only “club,” selling liquor on Sundays, running round-the-clock craps and poker games—but at the time it was difficult, for political reasons, to win high-level convictions under those laws (gambling and drinking were very popular). So while police regularly raided the Modern Horseshoe Club, they only ever arrested its patrons for “vagrancy” or “idling” and never pressed charges—a campaign of petty harassment, essentially. Jackson could afford good lawyers, though, and in 1908 he won an injunction against the police, effectively barring them from entering the club. “If the police are permitted to make such repeated raids, without good cause,” the judge wrote, “our government would soon be a Russian autocracy …”

The “permanent” injunction proved to be a temporary victory. In 1910, the circuit attorney charged Jackson himself with “being an habitual criminal and with running a gambling game.”

Police had intercepted an employee of the club who was carrying a bundle of clothes to a pawn shop. Pressed, he had admitted that gamblers had forfeited the clothes to cover their debts; they had literally lost their shirts.

Jackson’s power to intimidate was on full display during the trial. When Richard Sydnor, the wallpaper hanger who had decorated the club back in 1907, was called as a witness for the state, he “broke down, wept like a child and begged for protection, saying his life was not worth anything,” according to the Star. “He told the Sheriff he expected to be slain.” Another witness, “shivering with fear,” recanted his grand jury testimony against Jackson, accepting a perjury conviction instead. Meanwhile, six of the state’s eleven witnesses had fled the city.

The remaining five, however, apparently provided enough testimony to win a judgment against Jackson. His appealed it to the state Supreme Court, who in May of 1912 ruled that the jury’s instructions had been impermissibly vague and ordered a new trial. But on the same day, in a separate case, the court dissolved the Modern Horseshoe Club’s injunction against the police, holding that Jackson couldn’t seek legal protection simply in order to go on doing illegal things: “A plaintiff must come into a court of equity with clean hands.” This was a breakthrough verdict; it was now open season on the lid-lifting clubs of St. Louis. The following month, in the court of James E. Withrow—the same judge who, fifteen years earlier, had presided over the trial of Stack Lee—Ollie Jackson pleaded guilty to running a gambling joint, paid a $150 fine, and promised to close the Modern Horseshoe Club.

Recommended

The Ballad of Ollie Jackson

A Picture of Stack Lee

Crossing Paths